The New Gods is a mixed media artwork series by Egyptian artist Omar Houssien. Here the ancient deities of Egypt are reinterpreted through the lens of contemporary society, culture, and symbology. We see the god of disorder, Seth, as an Arab Spring protester, the goddess of joy and femininity, Hathor, as a belly dancer, the supreme Ra as an omnipotent president, or Nephthys as an influencer.

Combining the languages of pop art, advertising, and popular culture, the artist aims to create a critical reflection of contemporary and Egyptian society, as well as to offer a vision that is locally grounded, given that the Egyptian gods have become among the fantasy genre’s stock figures. All artworks were made between 2013 and 2019, during and as a reaction to the Arab Spring.

Each artwork (Mixed Media, 22×35 cm) is accompanied by a bronze engraved plaque (Faux-bronze, 10×15 cm), with a description of the deity. Similar to museum labels, each plaque had “technical information” such as major cult centers and names in hieroglyphs. The descriptions were written in a way that would accurately describe the deity, but push the viewer to draw parallels to the version represented.

Conveniently, we will take the image of the pyramid to visually convey the power stratification of The New Gods: from the supreme gods representing the state and military (such as Ra), then gods serving the government in various ways (like propaganda and religion), followed by independent shapers of the society (like Horus and Shu), and lastly ones outside the mainstream power.

Curator Srđan Tunić speaks with the artist about each individual god for Sumac Space in order to understand their past and contemporary image.

RA: listen to me, I’ll tell you… (2014)

Srđan Tunić: Ra had supreme power over the existing world. He was also the god of the sun and the kings. According to some interpretations, he was also the king of the gods and the creator of the universe. He was often presented with a falcon’s head, like Horus, with whom he was also paired as the god of the sky.

Omar Houssien: InThe New Gods, he swaps his falcon head for that of an eagle (the official emblem of Egypt and several Middle-Eastern and African countries) appearing as a generic politician, ruler, president, but – he is the face of the government. While he maintains the supreme power, unlike other gods (except for Seshat), the symbol is not on or behind his head, but on the podium, featuring the sun disk and the coiled serpent. With this detail, I wanted to pinpoint that it’s not the focus on the person, but on the position itself, the institution of the government. Ra is whoever stands behind that podium. In nurturing the personality cult, it doesn’t matter who takes the position, it is always the same (Ra).

AMUN: the people and the army are one hand (2013)

Srđan: One of the major deities of ancient Egypt, Amun was omnipresent but invisible, self-created and a creator deity. He was often paired with Ra (as Amun-Ra), making him the ultimate chief deity, and protector of the poor. His headdress has two vertical plumes which he (or it?) kept in your image.

Omar: I see him as the Egyptian military: omnipresent but never in the spotlight, maintaining the monopoly (and consequently the corruption) of power, and creating a model (one is forced) to be associated with as a dark presence looming over every government and president elected by the citizens. Historically, in order to succeed in ruling Egypt, you need somehow to appease the army. On the other side, it can be seen as an open and publicly-owned institution – one of Egypt’s few platforms for success based on meritocracy and social mobility. Military service is mandatory for all Egyptian men and so, the army IS the people. It is also one where the traditional protection of the poor is frequently implied. The military is a synonym for efficiency and is the country’s handyman, doing everything that needs to be done, also setting the desired role model for an average citizen.

OSIRIS: deep state (2014)

Srđan: One of the most important gods for understanding ancient Egypt’s obsession with the afterlife, Osiris was the god of life, death, afterlife, and resurrection, among others. Pharaohs were identifying with him, hoping to join him and become one in death. Traditionally depicted with green skin (color of vegetation and rebirth) and distinctive Atef crown. And this is the only god you depicted from the back, why?

Omar: Purposefully simple and mystical, I see Osiris as the deep state of Egypt. The power behind the power, completely in control yet cloaked from the public. While Ra was the role model during one’s lifetime, Osiris was celebrated in order to provide eternal (after)life. In such a system, where rulers were living for eternity, society doesn’t change and stagnates, being sacrificed to achieve this goal, like in necropolitics.

SOBEK: bow to me (2014)

Srđan: Sobek is the god of the Nile and the army, which had a very fluid and complex nature: at the same time benevolent and dangerous, warding off evil and protecting innocents, sacred and feared (as Sekhmet). Like head and tail on a coin, he embodies an army’s protection and terror aspects. Crocodiles in the Nile river were seen with the same double role: they were killing the pests hurting the crops, but also could eat humans.

Omar: In my interpretation, Sobek kept the crocodile appearance and the double-edged sword role. Posing and vested as a generic religious figure, his clothing combines elements of Christianity (white and purple robe) and eastern religions (halo, red ribbon, solar disk, and other attributes). Fluid and malleable as religion, bringer of peace, and fundamentalist terrorism, Sobek embodies religious authority which is responsible for a variety of conflicts in the Middle East. I think the religious authorities (embodied by the Muslim Brotherhood or the Salafist movement) were also pivotal in undermining the Liberal revolutionary movements post-Arab Spring.

BASTET: caTV (2013)

Srđan: The goddess of Lower Egypt and domesticated cats, also a protector against evil spirits and contagious diseases, and one of the defenders of the pharaoh. In the beginning, she appeared more as Sekhmet, the fierce lioness warrior, while later transformed in this more gentle aspect.

Omar: Here she’s presented as a TV anchor, one of the many talking heads on Egyptian Television, playing on the saying that there’s a cat in every home (in ancient times of course), now replaced with a TV. Despite being a protective deity, her role is not naive: representing the media, she is entering people’s private space. In the upper right screen, one can see a baboon (her helpers, also sacred) with a remote controller and inscription Latlata meaning gossip. The bottom left has a few elements, the first being the ka, which stands for one’s spirit or essence after death.

By incorporating it with the image of the media, I’m playing with the idea that the media (or propaganda) is after our soul. The background of the print is made of old state newspapers in Arabic.

ISIS: buy, buy, buy (2013)

Srđan: She was the ideal woman and mother, patron of nature and magic. Isis is personifying the pharaoh’s throne, directly representing the pharaoh’s power. Her headdress is literally the hieroglyph of the throne. She is one of the first gods, coupled with Osiris as her husband, from whom the first stories originated. And here – let’s start with the details, what’s in the background?

Omar: The background of the print semi-transparently shows home delivery and hotline ads from daily newspapers. The goddess herself advertises a product with a twist: while a product could be almost anything, generic and abstract in its shape (detergent? chips? dog food?), framed with a masonic eye and inscription Khara meaning shit. The Eye of Providence (the all-seeing eye of God) has roots in Christianity rather than Egypt and is often associated with freemasonry. That’s why here I wanted to create a visual pun, alluding to conspiracy theories that are often found in adverts and mass communication. This rather negative view of marketing as propaganda is reinforced with my own disillusionment with the advertising world. Additionally, Isis is also the emblem of Banque Misr, Egypt’s first national bank with Egyptian financing, further reinforcing her contemporary symbol for consumerism and propaganda.

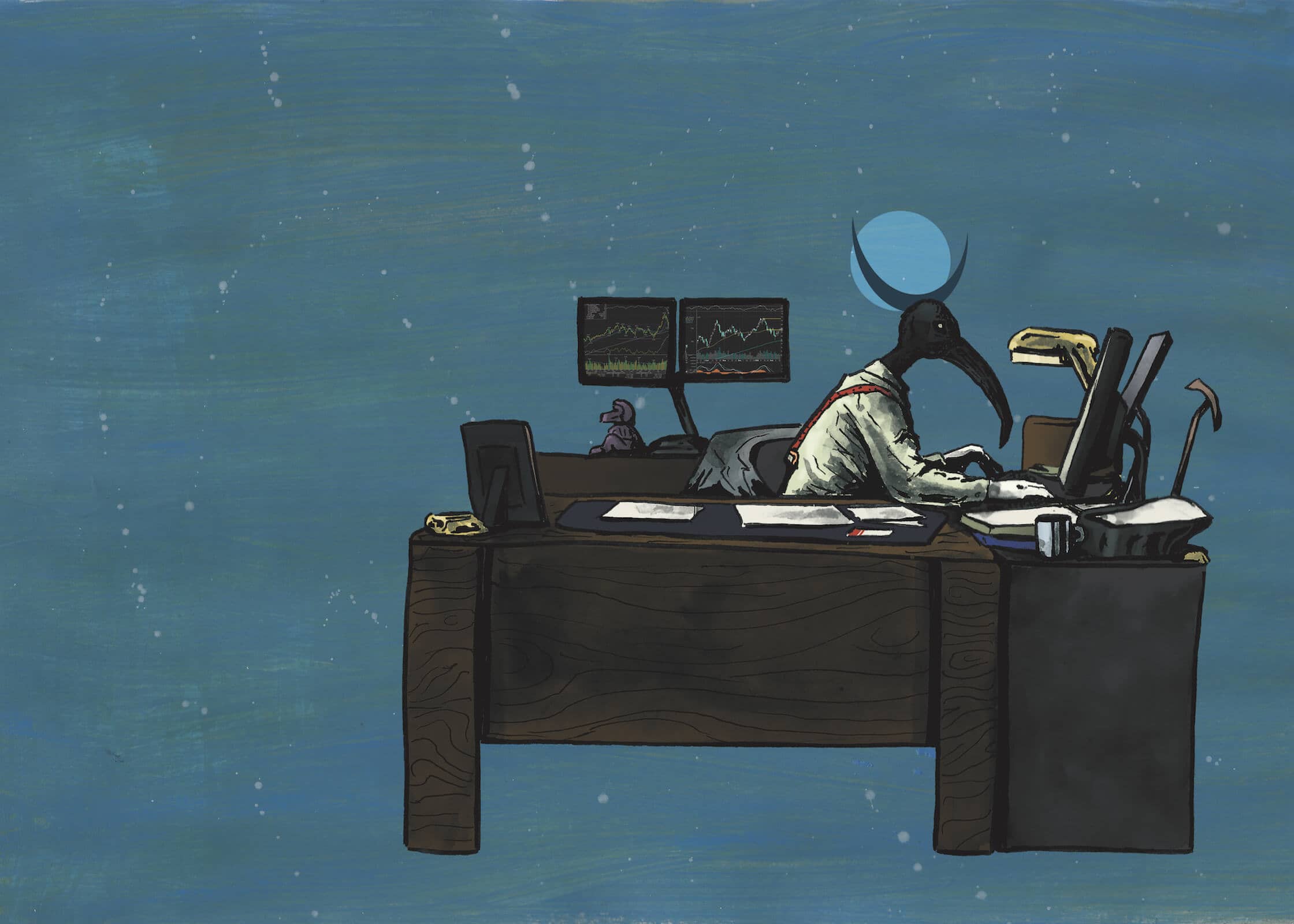

THOTH: knowledge is power (2013)

Srđan: The god of wisdom and knowledge, master of physical and divine law, it is said he himself calculated the making of heavens, stars, earth, and everything in them. A creative deity, he is recognized by the sacred ibis and baboon. Also related to magic and death – in the judgment of the dead, he was the one to record the results after measuring one’s sins.

Omar: In the new light, he is seen in an office, working as an analyst, related to the economy and the stock market. While time is money for Horus, knowledge is power for Thoth. Through data, he defines society as a white-collar level bureaucrat. Other potential reading could be surveillance. Whatever the case, he is an essential part of the system.

SESHAT: data harvesting (2019)

Srđan: Overlapping with Thoth, his consort, Seshat is in charge of wisdom, knowledge, and writing. She is the goddess scribe and record keeper, Mistress of the House of Books, in charge of libraries and archives (consequently treasury). She was recording the passage of time, mainly the pharaoh’s time on earth.

Omar: In our contemporary world, she switched to information gathering and data harvesting – the record keeper has moved online. The biggest social media companies are earning money based on collected data from their users, which is the reason why Euro bills are the background image. While everything gets digitized, not all data is important, which makes the record keeping pointless, emphasized by her making grimaces while taking selfies with her smartphone. Record-keeping is also inaccurate (our lives on social media are misrepresentations of our real lives) which is why on her bronze plaque, her name is misspelled. Just like in Ra’s case, her emblem – a stem with star-shaped petals and inverted horns – is not on her head, but on the item. The phone becomes the record keeper and an object of divination.

NEPHTHYS: the lady of the house/influencer (2019)

Srđan: I was trying to find more info on this one, but it’s rather scarce. This goddess was part of the top nine gods, known as the Great Ennead. Her function was the protection of the dead and “the lady of the house/temple”, signifying the pharaoh’s palace and priesthood. Her symbols are a house-shaped hieroglyph and a basket, also her headdress. Compared to some other gods from the pantheon, little is known about her and interpretations are fluid.

Omar: This gap definitely influenced my depiction. Nephthys is an influencer, creating a makeup tutorial. Like Bastet, she has access to other people’s private space and home through technology. Nephtys was heavily present in funerary rites, rituals mourning the dead and is a deity of protection, magic, and embalming. However, like you mentioned her largest role was that of the “lady of the house”. She is not a housewife, but influences the household, by setting the standards and desired image. The household in this sense is intended to mean the temple, the sacred space. Think about a subtle message: the temple or pharaoh’s palace could be your home.

Her hair, unlike the other gods, is typically Egyptian, curly, and natural, her role hasn’t changed in modern times. In some rural parts of the country, certain mourners are still hired to cry and scream at someone’s funeral, a similar job that existed back in ancient times by the priestesses of Nephthys. The background stripes are metaphorical mummification bands, relating it to her funerary aspect, which could be also linked to the makeup (understood as preservation of course).

HORUS: time is money (2013)

Srđan: One of the oldest worshipped gods from ancient Egypt, he is the god of the sky, war, and hunting. Usually depicted as a falcon or falcon-headed man, he is truly a symbol of majesty and power and served as a role model to the pharaohs. In your interpretation, he looks like a cool businessman, dressed in a smart casual way, looking at his watch, with a solar disk (a precursor of the Christian halo if I may note) above his head. Tell me more about his new image.

Omar: This is actually the first of this series to be produced. Horus is business and time related: time is money, money is business, business is power. He is a desired model of the all-powerful, an image of the entrepreneur. His image is still widely in use in Egypt (for example, EgyptAir’s logo and many businesses around the country). As such, I see him both as a protective deity and a sign of competition, through his ancient hunting role.

ANUBIS: shopping for eternity (2013)

Srđan: Anubis is of the most recognizable Egyptian deities, represented as a black jackal. The black color was associated both with the rotting flesh and the black earth of the Nile valley. He is the god of mummification and underworld, who weighs one’s heart before deciding if one’s spirit (ka) be destroyed or live eternally.

Omar: I depicted him as an elderly-looking shopper, he is an image of materialism, consumerism, and consequently capitalism.

Srđan: My initial interpretation focused on the cart, where most of the conserved products and their packaging could outlive our physical bodies, being fully or semi-artificial. But…

Omar: I’d suggest that the supermarket is related to another transitory and non-place, the tomb and the underworld. Through the process of mummification, people’s organs were preserved, and the burial included material possessions, sometimes even favorite pets and servants, ready to follow their master to the afterlife. I’ve alluded to this with the background, with its thick grainy brushstrokes simulating the earth. This stacking could also relate to the saying that you can’t take it all with you to where you’re going after death…

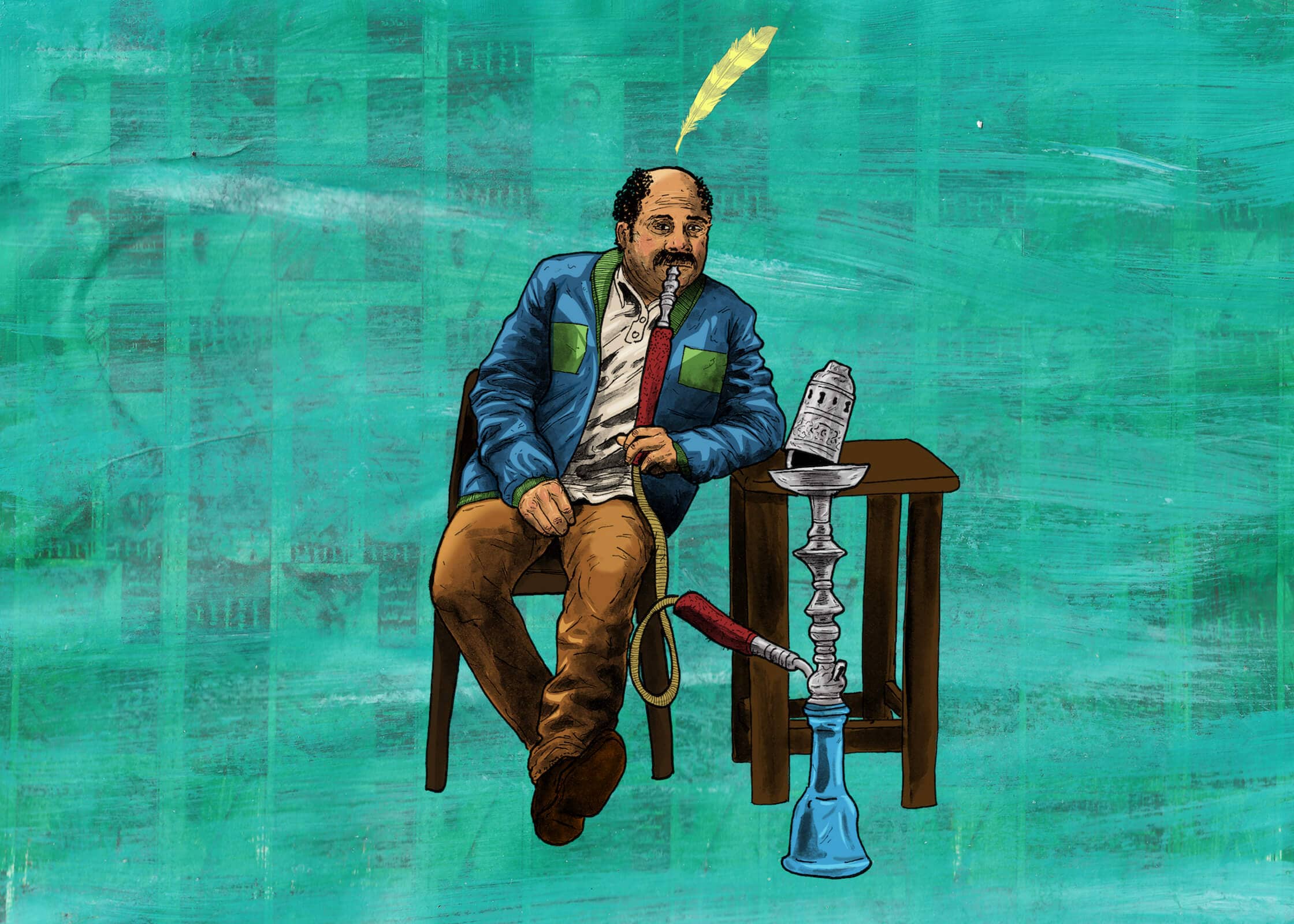

SHU: busybody (2019)

Srđan: A primordial god, Shu stands for air and wind, but is also “considered to be a cooling, and thus calming, influence, and pacifier”, often metaphorically seen as separating the sky and earth. The ostrich’s feather in him is seen as a symbol of lightness and emptiness.

Omar: In The New Gods, he’s smoking shisha, while in the background are warning messages from tobacco packaging. While his air symbolism is traditionally seen in a rather positive light, the pacifying role has been reverted to a vice. His pose is frequent in the Arab world: as a human CCTV, he’s monitoring others and creating a form of social pressure. After all, Shu has been separating the lover’s Nut, the goddess of the sky, and Geb, the god of the Earth.

A busybody who knows everything, imposing standards of behavior, looks, and norms. Interestingly, “Egypt is one of 15 countries worldwide with a heavy burden of tobacco-related ill health”, according to a 2015 report by the World Health Organization.

Another, more cultural and social take on Shu could be that of emptiness: the image of men smoking shisha in cafes is commonly associated with unemployment. The more time men spend doing this, idling as they watch and harass or judge neighborhood passersby, the more it’s apparent that they clearly don’t have work to get to.

MAAT: in vino veritas (2013)

Srđan: Justice, (the rule of) law, truth, balance, and morality, are closely associated with Maat. Her symbol is the ostrich’s feather and she was responsible for cosmic harmony. She, as a principle, was seen as a way to establish social order among the variety of conflicting groups and people living in ancient Egypt. In the Duat (the Egyptian underworld), she was one of the gods a person encountered in the afterlife when the hearts of the dead were weighed against her single feather.

Omar: My version shows Maat as happily drunk, with messy hair, clothes, and the ostrich’s feather. It’s as if you caught her at the end of a party. This viewpoint might seem desacralized, depicting the justice goddess’ fall from her duties. However, justice is elusive and can be manifested through excess (the bottle says in vino veritas in Latin, in wine lies the truth). She is also intended to be celebratory as Hathor.

PTAH: the crafter (2019)

Srđan: Another creator god, a pra deity, who, according to legend, existed before all other things and who conceived the world by thought and word. He is closely related to physical creation and is, therefore, the protector of all manual craftsmanship, as well as agriculture and the land. What’s his story now?

Omar: In this image, his agricultural aspect is emphasized, reminiscent of farmers who make up the majority of the population, but are neglected and unappreciated. He has the traditional green skin color, while his staff with symbols (ankh-djed-was) is transformed into a plowing tool. Farmers tend to be (and seen as) uneducated and poor, but a critical part of the society – after all, the whole ancient society came to be thanks to the fertile ground around the Nile. Even today, Egypt, despite being mostly a desert, is actually an agricultural country. Populist leaders (in Egypt, from Nasser to Sisi) often needed to get the farmers’ support to gain traction, and so they would do something for “the people”. The background is inspired by kilim tapestry patterns from rural areas.

HATHOR: dance, dance, dance (2013)

Srđan: The goddess of joy, feminine love, sexuality, music, and motherhood, she was also one of the companions of the deceased’s soul to the afterlife. She is usually depicted as a cow, or with a headdress with cow horns and the sun disk. I think this piece really needs the local context to be properly understood.

Omar: This is my favorite piece of the series. In my interpretation, she is a belly dancer, celebrating the body, femininity, entertainment, music, and love. She has the life symbol (ankh) and is one of the rare gods with a positive image in the series. I consider belly dancing – which originated in Egypt – is not given its rightful importance as part of contemporary dance. On one side, it’s recognized as part of Egypt’s popular culture (though ignored just like the pyramids and pharaohs), but on the other is also targeted by the conservative community due to body exposure, sexualized movements, and considered immoral. There is even an Act No. 430 of the law on censorship introduced in 2018, which states that “the dancing suit should cover the lower body, with no side slits, and should cover the breast and stomach area”, which Hathor happily refuses to comply with. The reading really depends on and reveals the onlookers’ ethics. If they are more on the liberal spectrum, they see the joyous tone of the piece, if they are more on the conservative side, they view her more within the same category as sex workers and consider it a cynical piece. Either way, it is one of the pieces I get asked most about, The role model for this image is the famous Egyptian actress and belly dancer Samia Gamal.

SETH: it’s either me or chaos! (2013)

Srđan: A complex and mysterious deity, Seth according to the myth of Osiris was responsible for killing Osiris and battling with Horus, and was seen as a god of chaos and disorder. He is depicted as what Egyptologists call Sha or Set animal, which appears to be a hybrid of “aardvark, a donkey, a jackal, or a fennec fox”. It’s not known if it was a real, misattributed, or extinct animal or even a fictional image. He was also the god of the desert, storms, and foreigners.

Omar: In The New Gods, Seth is a rebel, protesting and throwing a Molotov cocktail, wearing the Palestinian scarf (keffiyeh), which aside from being a symbol of Palestinian resistance, was used by protesters in Tahrir to protect themselves from teargas grenades. As such, he also represents the young people of the Egyptian Revolution. Here, just like with Hathor, the image is a test of personal beliefs, in this case, the political one. In one of his final public televised speeches in January 2011, president Hosni Mubarak famously said the revolution is a choice between chaos and stability, which was a constant justification for staying in power. Interestingly, during the Arab Spring, all the protesters at Tahrir square were accused of being foreigners, or foreign mercenaries, by the government, an accusation typical of oppressive and anti-democratic regimes. So depending on one’s interpretation of the events of the Arab Spring, this piece can be seen as either accurate or ironic.

Although traditionally portrayed as evil and adding to conflicting interpretations as an Arab Spring protester, I claim Seth is as important as his antipode, Horus. He is not bad or evil, rather creating a disbalance, a sign of social changes and otherness, the underdog.

Omar Houssien (b. 1990) is an Egyptian-Australian artist with a background in design, illustration, and visual communication. Having completed his studies at the European Institute of Design in Milan, Italy, he returned to Cairo where he contributed work to art spaces and cultural initiatives, development programs, and various advertising campaigns.

In 2017, he participated in his first artist residency as part of the East Type West Type program at AGA Lab, culminating in a two-week exhibition at the Bijzondere Collecties (Amsterdam). From 2014 to 2018, he worked on the independent film Poisonous Roses (Cairo), which premiered at the Rotterdam Film Festival and won several awards, eventually becoming Egypt’s 92nd Academy Awards submission for Foreign Film. In 2019, his work The New Gods was exhibited in Roznama 7, organized by Medrar for Contemporary Art (Cairo). He has had previous exhibitions in Cairo, Amsterdam, Milan and Belgrade. Instagram @oh.youfoundme

Srđan Tunić (b. 1984) is a freelance curator and researcher based in Belgrade, Serbia. He is a co-founder of Trans-Cultural Dialogues (as part of Cultural Innovators Network), Kustosiranje / About and Around Curating and Street Art Walks Belgrade initiatives. He is collaborating with art professionals, researching fields such as contemporary art, curatorial practices, street art and graffiti, science fiction, art appropriation, cultural diversity, experiential learning, independent cultural scene and self-management.

His texts have been published in the Kultura Journal, AFRIKA – Studies in art and culture, Transcultural Studies Journal, IJOCA – International Journal of Comic Art, SAUC – Street Art & Urban Creativity Scientific Journal, as well as web portals SEEcult, Uneven Earth, Balkanist, Makanje and Seismopolite magazine. www.srdjantunic.wordpress.com

Sumac Dialogues is a place for being vocal. Here, authors and artists get together in conversations, interviews, essays and experimental forms of writing. We aim to create a space of exchange, where the published results are often the most visible manifestations of relations, friendships and collaborations built around Sumac Space. If you would like to share a collaboration proposal, please feel free to write us. We warmly invite you to follow us on Instagram and to subscribe to our newsletter and stay connected.