Farzaneh Abdoli: I would like to start by sharing my own experience as an artist and see if anything resonates with the way you see your practice.

One of the most fascinating phenomena that I have experienced during my artistic activity is that I am continually identifying myself throughout my work, and I am continually questioning myself in relation to the purity and accuracy of my choices. I have studied Freud’s psychological defenses a bit and I have recognized that my work portrays this; my artistic activity becomes a foundation to improve this kind of cognition. Psychological defenses are those individual reactions that we show automatically and unknowingly to escape and avoid difficulty and stress. A person cannot consciously perceive them because they frequently occur in us before learning the language. The human mind reacts subconsciously before experiencing emotional pain in situations where it may be stimulated.

Accordingly, I believe self-reflection is a highly complicated and difficult task. I was constantly identifying phenomena in myself that I was incapable of seeing in my previous project, Melancholia, and I decided to recognize what was really happening inside me and to tolerate difficult experiences so that I could manage them. As I deeply considered and analyzed the issues, feelings, and forces were gradually formed within me that led me to my choices to create the artwork. I created the work in a highly exploratory style and as part of a long process, and I was not entirely aware of the details of what was continually forming. This process is similar to solving a puzzle; it is both stressful and joyful simultaneously. The most pleasant part of being an artist, besides the feeling of freedom, is the opportunity to meet reality and fantasy without fear, and to examine them. Undoubtedly, I experienced many pleasant and unpleasant feelings throughout this process, and it creates my life experiences.

How does this process take place in your artistic practice? Where do you start your artistic activities?

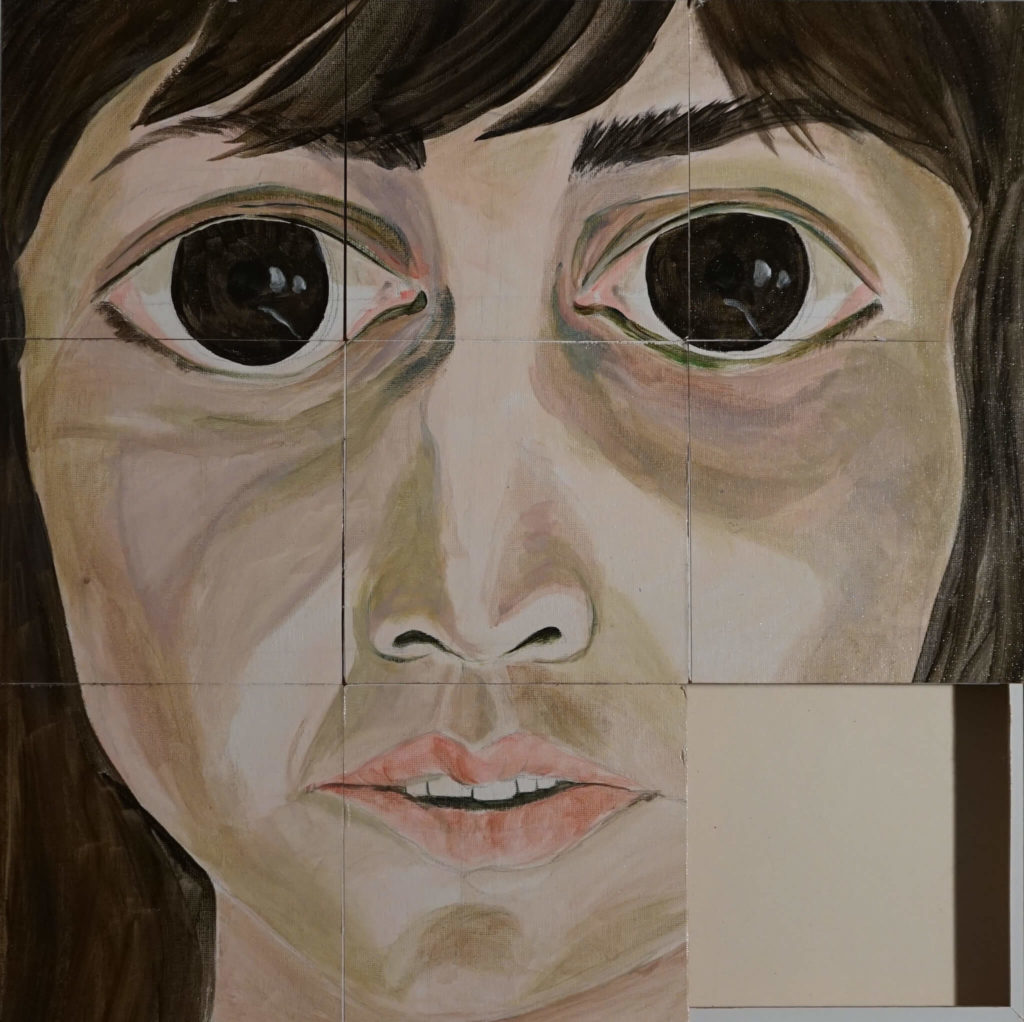

Ahoo Maher: My process is a bit different. I started the Diary project eight years ago because I wanted to document my everyday life. I’m not a good writer, therefore I started to record my days by drawing in my own style. I continued this routine for a few years, creating one drawing every day that was inspired by various daily events and news. The drawings then became more and more personal and turned into self-portraits. Unquestionably, one can see the effect of social media on them. I attempted to express my feelings and emotions in these self-portraits, which then shaped the project Faces – an interactive project in which several self-portraits were displayed in the form of slide puzzles whose position could be changed by the audience.

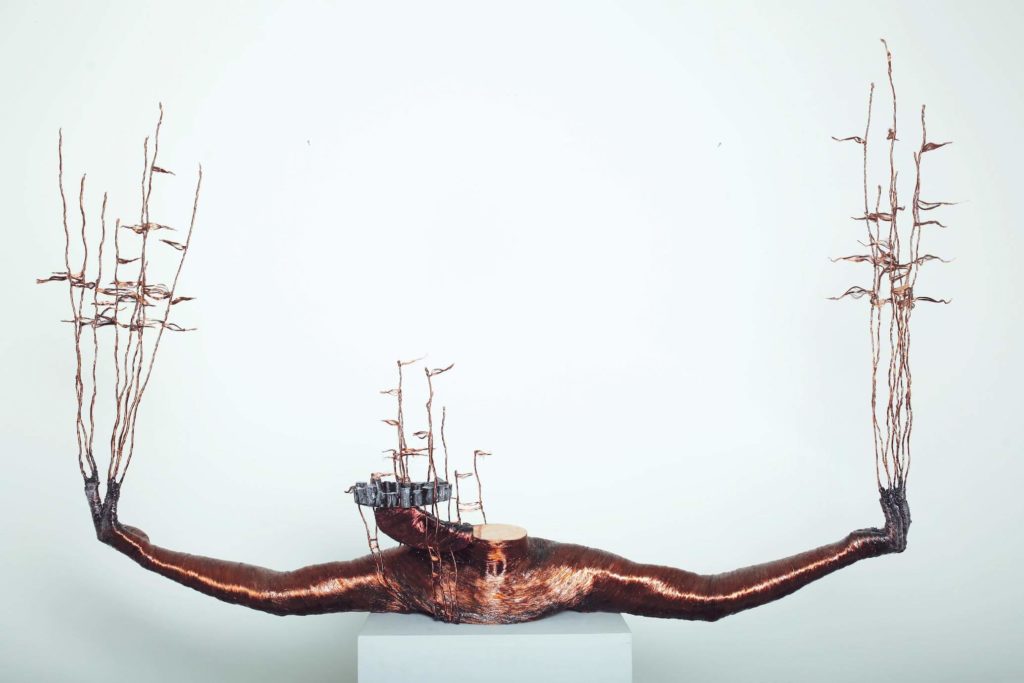

Another project, Hejleh, originated from my own interest. I once traveled to the south of Iran, where I attended a wedding party. The bridal chamber attracted my attention. This initial interest resulted in several years of research, that later led me to observed the chamber of mourning. The shapes, colors, and spaces intrigued me and transformed into an installation project that grew during the time of research.

Moreover, I have always carried out other projects in parallel; I have worked in the field of performance and curated projects, and as a result, they affected and complemented each other. The subject of most of my work comes out of my daily struggles, and I really can’t tell when exactly the project starts and finishes, because it goes on for as long as needed. It might take me a while to get through a project, which can be a platform for new ideas while it is still in the works, and so several other sets that are ultimately related to each other pop up.

Farzaneh: I want to talk about your recent project, After Party. How do you decide what an artwork needs to say to the viewer? That is, what do you intend to achieve with After Party? I am asking this because I am constantly challenged by the balance between self-expression and communication with the audience. I think, “What will happen when I explain and show my inner feelings to others!?” Sometimes it is even hard for me to think about this issue because it is constantly possible that you are not understood and there is no connection between you and your audience.

Ahoo: I think art does not always need to have a function or purpose. Of course, it can be significant and convey meaning, but I assume that art is often produced out of necessity. I do not intend to criticize or confirm anything; I am just showing people’s lives from another angle so that other people may look at them similarly and agree with me or find recognizable elements in them. I do not intend to present news; rather, I want to think, to look around with no judgments, and invite others to join me. I want to look at my surroundings from the outside and notice the concerns of my generation and their effect on me.

Farzaneh: In any case, you examine and analyze a subject and create an image, you bring that moment of reflection to your work, and eventually, you describe and write a story that you have created in your mind. Do you think it can be summarized by saying that you desire to create a moment of reflection?

Ahoo: In regards to After Party, I would say that my starting point was the emptiness and meaningless feeling people sometimes experience when they go back to their lives after a party. In my view, this is not necessarily positive or negative. I desire to have a neutral perspective, neither approving nor rejecting it. I can say my standpoint is a moment of reflection.

Farzaneh: Do you intend to become more engaged with the issue as you work? Do you wish to convey a message that is driven by your personal perspective?

Ahoo: Absolutely. Since this subject is transmitted through my vision, it is personalized. Therefore, I set the details of the work in a specific order that can generate the feeling I wish to convey.

Farzaneh: I see a very clear and personal message in Banksy’s work, which conveys a social message using his way of observing and making the most beneficial use of his media. Would you agree that if the artist is informed by his/her surroundings, their perception will become stronger, and the artist can explain their messages more explicitly and clearly? I think that possibly, if this maturity increases, the artist can affect the audience more deeply, or maybe even ask deeper questions.

Ahoo: I assume people’s understanding of life changes as they get older. When it comes to artists, I believe this is also influenced by shifts in artistic periods because artistic work is not separate from the person – what happens to the artist also happens to their work. Of course, when a work of art reaches the point of presentation, the artist aims to convey a message and wants to share with the audience what they went through or learned. But I do not have a message about the dos and don’ts in the process of developing the work. For example, when I start a project, it is often after I have had questions and thoughts about the subject for years. I’m not just talking about whether this is a good thing or a bad thing; I am stating that we should simply look at it again because it’s ours. This is the life I am experiencing, I recognize this, and of course, it may not appear like a great social issue at first glance. I try to express myself in a simple and tangible language. There’s a wide variety of artistic practices, and art is not always critical. But as far as I have experienced, sometimes the issues that I introduce involve significant social concerns, even though I express them in terms of my perspective, experience, and cognition to make them tangible and to speak of them with honesty.

Farzaneh: As an Iranian artist who lives in Europe, how do you find your way and identity in the international field?

Ahoo: Being a student in Europe was a wonderful opportunity because you are supported everywhere. As a young artist, when you hold or attend an exhibition or competition, you are always in the spotlight. But when this period is over, all this support is eliminated. Entering the art market becomes extremely difficult. Yet, there are opportunities to make a living and continue working as an artist by participating in art fairs, for instance, and performance and conceptual art are supported by public and private funds in order to create projects. There are also opportunities for the younger art spaces and projects, so that they can independently pursue their artistic activities somehow separately from the art market.

As to my nationality, here in Austria, I do my best to follow my independent path as Ahoo, apart from my nationality as Iranian. It is definitely not easy as a 30-year-old female painter, though. I am inspired by Iran and my background, which is undoubtedly visible in my work.

Farzaneh: Are there international artists that you value in particular?

Ahoo: There’s a difference between the international art world and the art market. When you enter the market, the value of your work increases exponentially according to the principles of the market, but when we look at the artist we still consider their background and artistic path. I think David Hockney is one of the most intelligent artists of our time. I saw his works two years ago at the Centre George Pompidou. He started first with drawing, and when Polaroid developed, he started to work with Polaroid photography while creating the well-known series of swimming pool paintings and his many other prominent works. Hockney is so intelligent that he is constantly in line with the changes and media of his time and has always progressed. Although he signed a contract with Apple to produce videos in partnership with them, he could never be identified simply by those videos. We know him due to the process he went through as an artist, and we give meaning to those videos. He follows the state of the art so well with a remarkably high social intelligence and adapts himself to societal changes. I think it is incredible.

Farzaneh: How much do you think the market affects the concept? What is the relationship between the two? What is this distinction in your mind?

Ahoo: I think it is entirely personal and they can be separated. We can have an idea of which works are more “sellable”, and sometimes that influences the types of work artists create. Some topics are noteworthy, such as global warming, which is currently a significant issue, and it is the right time to present a project on this topic. If you come from the Middle East, there is an exotic gaze, which is preferred by Western society. This generates temptation to work on such issues even though it’s not your concern, because it might draw the attention of the market. But frequently there are both concerns and cyclical synchronicity. I cannot imagine changing my subject based on the market because my work is driven by my personal need and interest. In fact, it is by choice that I have not yet entered the larger art market. The path I have chosen to pursue with my art will not take me there very promptly.

Farzaneh: I feel that those who purchase works of art are often quite conservative with their selections; they often prefer to purchase reproduced or modern concepts, or works that guarantee their investment. Innovation is not as valued. This influences artists’ activity.

Ahoo: Naturally, the path is difficult because you are not supported in some situations. But on the other hand, the path is more sincere. Because when we perform a task creatively or innovatively, it may not be accepted at the time or place of its debuted presentation, but it does not mean that the work is bad. I do not wish to see results very soon. I know that I am happy with the work that I am doing, and I think that when artists go their own way, independently and sincerely, they often see results at some point. Of course, we have to live and pay for living expenses, but more than that, we should not care about the market and we should move forward with confidence and strength and continue on our path.

Ahoo Maher, born in 1990 in Tehran, lives and works in Vienna.

Maher studied Music at the University of Music and Performing Arts Vienna. She furthermore graduated with a Master’s degree in contextual painting from the University of Fine Arts Vienna.

The main theme of her work is living conditions from the perspective of women, which she explores through different media such as paintings, installations and performances.

Ahoo Maher’s work was presented as part of the CHARBAGHS (Four Gardens) project from 10.03 – 30.09.2018 at philomena+ in Vienna, Austria.

https://philomena.plus/programme/hosna-pourhashemi-charbaghs-four-gardens/

Farzaneh Abdoli currently lives and works in Iran. She is a member of the Association of Iranian Sculptors and has participated in several exhibitions, including the 5th Tehran Biennial of Sculpture at the Museum of Contemporary Art. In 2008, she was part of the first Biennial of Urban Sculpture and one of her works was selected to be installed in the city. In 2009, her first public sculpture called Fish Wave was installed along the Sattãri Highway in Tehran. Abdoli is also one of the winners of the second Urban Biennale. In the same year, another work of hers was installed in the public space, at Kosar Square in Mashad. She furthermore created the rainwater fountain under the Seyyedkhandãn Bridge in Tehran. Farzaneh has participated in many group exhibitions of the Association of Iranian Sculptors.

Dialogues is a place for being vocal. Here, authors and artists get together in conversations, interviews, essays and experimental forms of writing. We aim to create a space of exchange, where the published results are often the most visible manifestations of relations, friendships and collaborations built around Sumac Space. SUBSCRIBE NOW TO STAY CURRENT.