Some of the information presented in this text might be fictional. Thus, the author is leaving complete freedom for the reader to decide upon what might be factual or fictional.

The presented self-interview of Huda Takriti interrogates her multi-media installation of cities and private living rooms (2020) and reveals central interests of her work: the agency of lost archives and hidden biographies. In of cities and private living rooms a domestic mystery unfolds into a visual essay where images, family archives, various landscapes combined with text and memory intertwine with fiction, reality, the (hi)stories of migration and diaspora, identity and representation.

Q: Could you take us chronologically through the background of your work? When and how did you find out about your great-grandmother’s “secret” identity?

A: It all happened by the end of 2011, during a conversation with my older brother. He mentioned that he was wondering if there is a possibility to get a Polish passport if he can prove the origin of Fatima. Nevertheless, he was not sure if my mom or her family would want to speak about this openly!

That’s when I found out that my great-grandmother whom I had never met in person, but still have heard so much about, was in fact not completely the person I thought I knew. Fatima was not Lebanese. At least, not for her entire life.

You can imagine how shocking it would have been for me to hear that piece of information. I thought that I already had a complex background; A Lebanese/Palestinian mother and a Syrian/Iranian father. Suddenly something else was added to the already complex batter.

My brother did not have much information. According to him, Fatima was Polish who managed to come to Syria with her family before or during WWII. She later moved to Lebanon. His source was one of our relatives who managed to track down a couple of Fatima’s relatives on Facebook. She even ended up meeting one of them; The grand-daughter of Fatima’s sister “Jamile” who now lives in the USA. My mom asked him not to share this with anyone when he tried to get more information from her. But it was too late for him to back off!

Q: And what happened next?

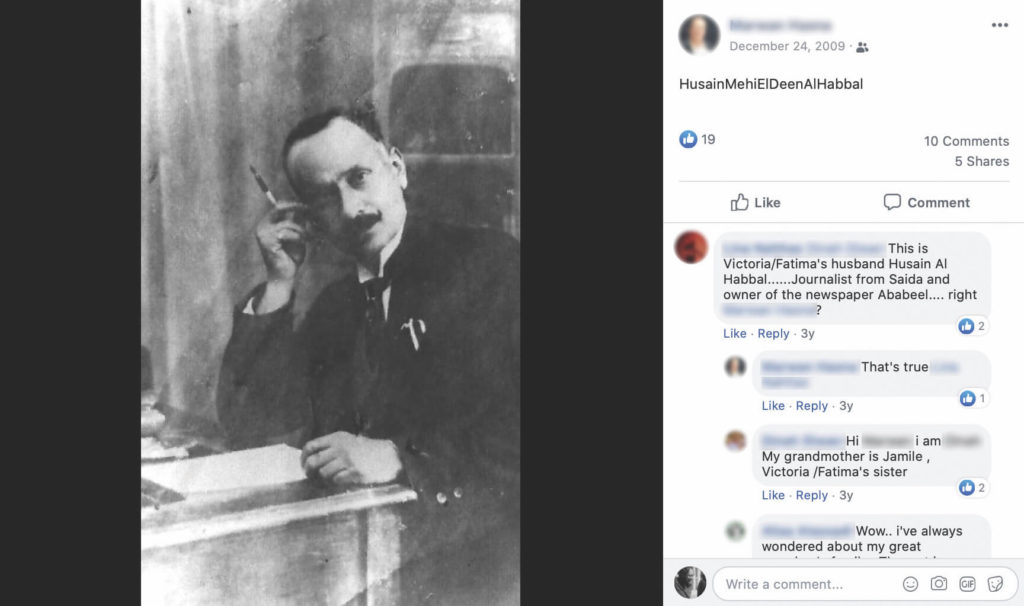

A: Well, the first step I took was to go to my mom and ask her if this was true and for what reason was this kept a secret… At first, she refused to talk about it and constantly repeated, “There’s no need to talk about this” and “It’s already buried in the past, there’s no point in digging it up now”. However, after insisting for a while she shared her version of the story with me; Fatima was born in Damascus in 1887 to Polish parents whom have immigrated to Ottoman Syria1. Her birth name was Victoria. Later in her life, Victoria traveled to Lebanon where she got married to a Lebanese Journalist and founder of Al-Ababeel newspaper, my great-grandfather “Hussain Al-Habbal2”, who gave her the name Fatima. She lived her life between Saida, a city in the south of Lebanon, Damascus and Kuwait. She died in Saida in 1967.

Q: So, your mother and your brother’s stories were somewhat incoherent?

A: To some extent, yes! Some of the details shared commonalities. I must mention both my mother and my brother were very sure of their versions. My mother was raised in Saida by her grandmother “Fatima” as her parents were working in Kuwait and wanted her to grow up in Lebanon. She says that Fatima was her best friend till the day she died. So, I consider her to be a reliable source of information. On the other hand, my brother’s source of information was proven by Fatima’s extended family member in the USA.

The more family members I’ve asked, the more versions of stories I encountered. Such discrepancies between the narratives became the starting point for this work. When Victoria’s/Fatima’s birth certificate showed up, it became even more confusing. The stories, at first, had a common thread, Poland. Moreover, after I finished the work last summer there was a new story mentioning Russia as the place of origin of Fatima’s parents.

Before the new story come to surface, there was a debate on which city or village did she come from. Some said Warsaw and others said Gdansk, and a debate considering the historical period of their departure. With an aim to find a trace of some kind of a historical record or a document which may lead me somewhere further, I left to Poland.

Q: But you have mentioned finding Victoria’s birth certificate. Didn’t it lead you somewhere in your research?

A: The birth certificate was issued under the name Fatima Al-Shami, and it was later revealed that my great grandfather, Hussain, had this document made for her after their marriage. She kept this name when she chose to convert to Islam later in her life.

Q: It seems like you’ve got a lot of fiction going on in your family’s history. How do you reflect on what is factual and what is fictional in your work? Is it important for you that the viewers are able to distinguish between the two?

A: The work consists of two parts, a film installation and a family photo archive. Hints were implemented for the viewers here and there. In the film, I don’t only reflect on what is there I try to reflect on what is not there as well. By borrowing items from the photo archive and implementing them into the film.

The archive is shown via slide projection, the photos are real, what the viewers see is real. Nevertheless, the material and the form of the photos are manipulated. I don’t know if the original photos still exist somewhere but one relative had a digital copy of the photos uploaded to Facebook.

The photos I am using were downloaded from Facebook and then returned to their analog state. In this process, some information and details of the photos were hidden away. The viewers can still see pixels and parts of the torn photo edges in the slide projection. Moreover, I leave it to them to decide what could be real and what not.

Q: The act of restoring or returning the photos to a unity that might not exist anymore suggests a form of fictional archive. Does it exemplify your tendency to collaborate with and rework historical material?

A: Honestly, I didn’t have a good sense of what exemplifies my work while working on this project. I’ve always been drawn to fictions that have documentary tendencies, and documents that open fictional pathways. It’s more clear for me now that I love to be on the edge between the factual and the fictional.

Q: In your video installation, the first question the viewers are confronted with is “Do we need the truth?”. One can say that the phrasing of the question is a key to the work. To whom are you addressing the question? Are you including yourself with the viewers?

A: There’s a big difference between saying “Do we need the truth?” and “Do we want the truth?”. Personally, phrasing the question this way was a reflection on the stage of my research where I realised that there is no point of seeking the truth anymore; Funny that these were my mom’s first words to me and it took me about eight years to realise that. Moreover, it was a hint left to the viewer about the process and how seeking the truth, this one truth in regard to others, appears to get lost further and further.

Q: This question comes after we hear your moms’ voice reciting what seems to be a memory of her grandmother at first which turns out to be a dream. Can you elaborate on the sequence of the narrative in the work and on the way the archive and the video installation engage in conversation with one another?

In the work, both the photo archive and the film installation are connected to each other. as you mentioned, the film begins with my moms’ voice reciting a dream she had the night Fatima died in 1967 during a phone call we had. At the time I was in Poland. She always finds a way of talking about a dream she had had when she is questioned about any topic. And that found its way to the visual narrative of the work which is constantly blurring the lines between dream and reality.

The narrative throughout the film is set to unite it with the photo archive. It starts by listing items and objects we can see in the photo archive, as if the narrator is looking straight at it. The narrative continues with comparisons and reflections on the images and places we see in the video. Geographies and archive images melt together into a visual essay.

Q: You shot the video in Poland. Can you speak about the connection between the locations you filmed in and the story you are narrating?

A: I went to Poland with an aim to find a lead to some kind of truth. Instead, I was surrounded by a landscape that carries a certain history. A history which most of my family members relate themselves to without being 100% sure of. I began to think about spaces and memory, how we relate ourselves to an unknown space.

I don’t know if you are familiar with Masao Adachi’s3 so-called Landscape Theory or Fukeiron, a strategy that Adachi implemented in his 1969 film AKA Serial Killer, which suggests the possibility of creating a portrait of someone through capturing the physical landscape that shaped them.

I was not interested in dogmatic adaptation of Adachi’s theory. My interest here lies in reversing it and searching for possibilities of positioning a person to a certain site or historical context. Time in Poland had me thinking of possibilities of creating someone’s portrait made up of patchy memories and unproven facts.

The landscape we see surrounded me during my time there, the narrative we hear is constantly referring to this landscape as one from a memory or a connection from the past. I never reveal the mystery of the work or the place it was filmed in till the last scene of a marathon in Warsaw; Warsaw becomes somewhere in-between a question and an answer – an imaginary ending point of sorts.

1 Ottoman Syria refers to divisions of the Ottoman Empire within the Levant, usually defined as the region east of the Mediterranean Sea, west of the Euphrates River, north of the Arabian Desert and south of the Taurus Mountains. The Middle East and North Africa: 2004, Routledge, p1015.

2 Hussain Al-habbal was born in Beirut in 1869, founded Ababeel newspaper in 1895, which was a political one. He criticized the alliance that had been established between France and Britain to divide the Middle East, so the French High Commissioner General Maxime Weygand sentenced him to prison in 1919. I. Kreidieh, Sons of the East p 496 – 497.

3 Masao Adachi (足立正生 Adachi Masao, born May 13, 1939) is a Japanese screenwriter and director who was most active in the 1960s and 1970s. He is best known for his writing collaborations with directors Kōji Wakamatsu and Nagisa Oshima

Sumac Space is a venue for raising questions and conversations.

It is updated regularly with new, fresh content.

Subscribe to the newsletter to be kept up to date.

Huda Takriti (Damascus, 1990, lives and works in Vienna, Austria) is a transdisciplinary artist based in Vienna. In her artistic practice, she explores the relationship in between history, politics, memories and counter memories and the construction of our own subjectivities.

She uses different media to work with these issues, such as video, film, installation, painting, and performative situations. In most of her works, she tempts to generate questions about how we relate to others, how we tell personal stories in the frame of the collective history and how do we deal with our patrimony and traditions.

Takriti has participated in many international group exhibitions and festivals, including exhibitions at Universitätsgalerie im Heiligenkreuzerhof (Austria), Kunsthalle Wien (Austria), Afro Asiatisches Institut (Austria), [.Box] Video Art Project Space (Italy), STIFF Student International Film Festival (Croatia), Stiftung Mercator (Germany), Kunstraum Lakeside (Austria), Centre d’art Sa Quartera (Spain), Addaya Centre for Contemporary Arts (Spain), Krinzinger Lesehaus (Austria) and University of Applied Arts _ Die Angewandte (Austria).

Huda received Kunsthalle Prize 2020 (Austia), Ettijahat Production Award, Laboratory of Arts, 7th Edition 2020 (Lebanon), Styria-Artist-in-Residence fellowship 2016 (Austria) and BMUKK and Kulturkontakt Austria residency fellowship 2014 (Austria).