You moved to Baltimore in August 2014. What is the situation like being an “Iranian artist” living in the USA?

It has been pretty tough and fun. It depends where you land in the US, in LA or NYC or Baltimore… I actually do not know about being an Iranian artist in the US. I think it requires an insane amount of relentless reductionism to talk about an Iranian artist in the US in terms of identity. I can only talk about Taha in Baltimore from 2014 to 2020.

The amount of uncertainty for individuals who happen to be from certain countries and represent different ethnicities can be insanely overwhelming, but also productive. I decided to take all of it and try to examine my capacity and thresholds, and turn it to an existential challenge. The continuous anxiety about my status and visa made me so conscious of the presence of state sovereignty, my own physical presence in this country, and the idea of borders, passport, and ID. The language and culture were also a big project. In the last six years I have barely had anyone from Iran around me and most of my friends are Americans, and that itself has required a massive rewiring of my brain. I have not been able to go back to Iran in the last five years, and adding that to dramatic financial turbulence and maintaining a full-time artist status, I had to be a tightrope walker and be careful about my lifestyle to manoeuvre through life with minimal support.

There are also professional and art world issues which I can write a novel about. One of the biggest challenges for people like me is the Western gaze, which creates sets of very rigid categories and fetishistic expectations for POC in both society and art institutions. There is a lot of temptation to submit to those expectations, and I have been trying to be cautious about them. I mean, the art world demands that artists of color paint certain things and use identity branding, in my case with a hint of Iran/Islam, just at surface level and in a way that is easy to consume for Westerners. It is easy and boring to play the identity card and overdose on it so the art world can call you a successful artist without the art world itself having to do any heavy lifting in understanding the complexity of “the other” and their fundamental role in creating the other.

This strategy seems very important if one considers the attempts of art history to break away from a Eurocentric orientation. What is the remedy for this art world issue? How can artists escape from this labelling system of art institutions?

The Eurocentric orientation is too omnipresent and embedded in every particle of each museum and every word of art history that it is impossible to locate it as an empirical system or realm, so we can not find ourselves out or inside of it. However it is possible to recognise its attributes; for example, the fact that I am responding to this question in English or that I am called a “Middle Eastern” artist is capitulating to Eurocentrism.

I don’t think it’s a question of breaking away or finding a remedy. I think it’s a matter of messing with Eurocentrism’s attributes and creating new concepts. When you try to fix something, you’re investing in it. There’s an impulse to try to “tip the scales” by inflating representation of non-Western identities, but this in itself affirms that East-West polarisation. I prefer to take a more Deleuzian approach, which says that identity is not prior to difference. So we need to establish new dialogues that invest less in identity and more in non-hierarchical and rhizomatic connections.

You received your BFA from the Art University of Tehran. How does art university work in Tehran?

My understanding of my education at Art University of Tehran has changed since I attended the Maryland Institute College of Art, which gave me a dichotomy to compare and contextualise the differences in education in the US and in Iran. It is also hard to separate Tehran as an ever-changing, living being from Art University as an institution. The time I was a student at Art University of Tehran coincided with many social and political turmoils in Iran between 2009 and 2010, so my experience of Art University was very much influenced by its location in the heart of Tehran.

There were definitely many great things happening in Art University of Tehran which I have not seen or experienced here in the US. I am talking about an urgency and necessity to be critical and have continuous conversation about things happening in our peers’ work as well as our social and political environment. My classmates and I formed an independent, small group of students within the school, engaging with ideas that were more contemporary and progressive than what Art University of Tehran was offering, and younger teachers like Alireza Sahafzadeh had a major role in forming those circles. We were working in our studios before teachers showed up and stayed late till the security kicked us out. We kept pushing and challenging each other because there was a sense of lacking in the institution. The structure of Art University of Tehran draws from Western concepts, and the content of the class is also Western, and the education itself is the recycled education our teachers received in a bygone era, so as a student in Iran it all feels secondhand. It feels like there is a gap between what we’re doing and what’s actually happening in the contemporary artworld. I mean, who needs a teacher who has not changed his syllabus since he graduated from Beaux-arts in the ‘60s? That gap breeds distrust in our experience of art school.

What I have experienced here in the US is a trust in institutions as job providers or gatekeepers of success in the artworld, though that trust is based on myth, and a more democratic class structure in which the mentors have less authority than they would in Iran.

You are interested in “the simultaneity of multiple material applications to create the painting [that] reflects the various modes of image reproduction and dissemination that occur at any given moment in the history of an image”. Could you elaborate on this?

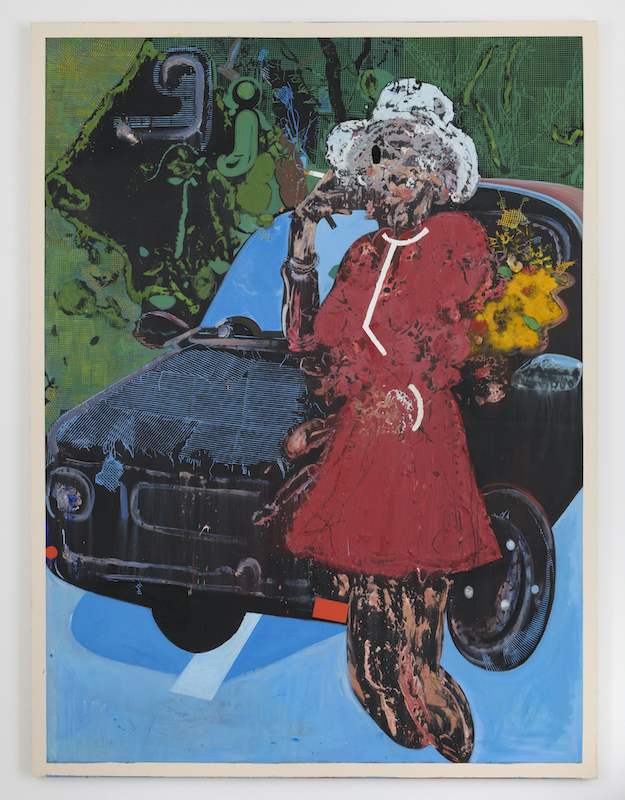

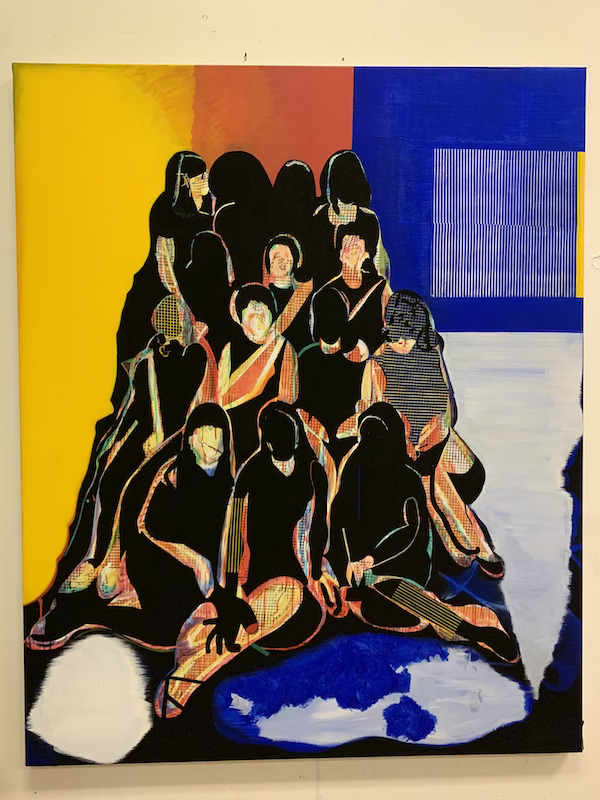

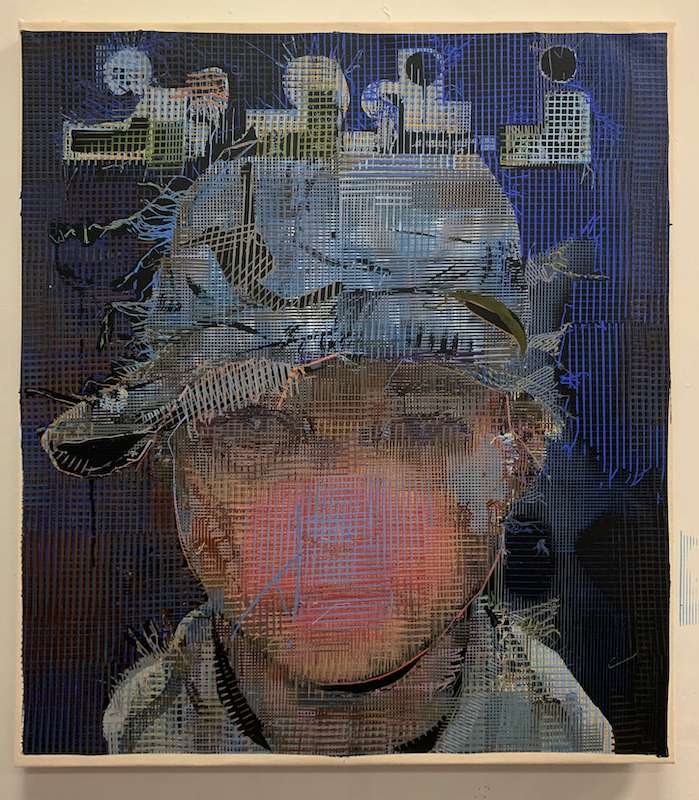

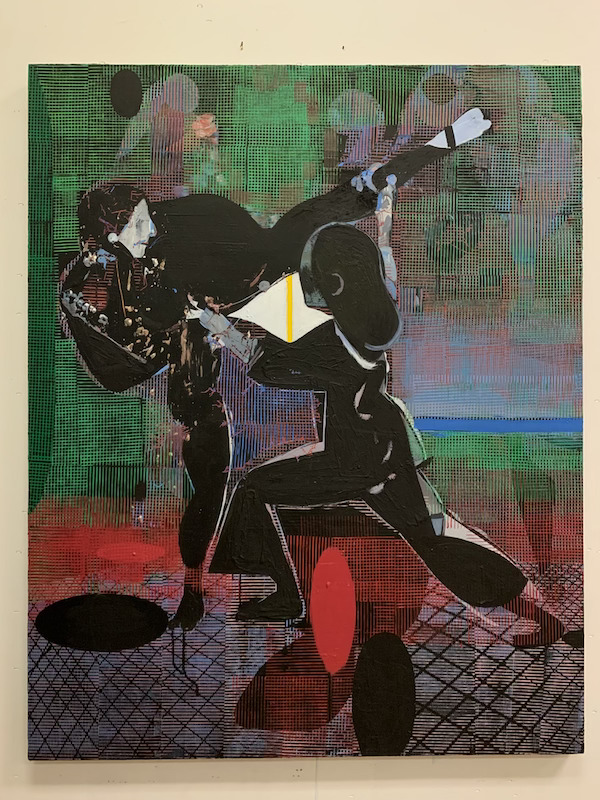

I am interested in painting as a medium and its material condition including the technique or mechanical approaches of applying paint on the surface, from the cave paintings to Jackson Pollock and Katharina Grosse. All these different systems of mark making, or technics, are symbolically and historically shaped by political, social and economical forces. So technics is not just a possibility; as Bernard Stiegler puts it, “technics is the condition of culture.” I tend to focus on this question of application, through which I am left with how instead of what. How do these pictures of Zan-e rooz magazine from before the Islamic revolution of Iran exist? Are they analogue existing on light-sensitive paper coated with silver emulsion, or on inkjet printer paper, or are they pixels on my screen or algorithms in a data center in China, or all at once? And how does one paint that multiplicity and simultaneity?

You claimed that “you keep working on your old paintings”, meaning you don’t see any finishing point for them. Does this relate to the idea of painting as a “thinking act” instead of “expressing thoughts”?

Thinking act is actually a good way of putting it, but it becomes very Cartesian. I am not sure if I think as much as I stand, breath, touch and drink, listen and dream… so it would be great if we can add life to this thinking act. Everything we do is “in order to” — I drink water in order to not be thirsty, I make chairs in order to sit, and I sit on the chair in order to relax but I cannot simply apply this to the act of making a painting. I do not make paintings in order to do something else; that itself makes the act of painting an open ended act. So instead of using the word “finished,” painting I would use “a temporal pause.” This pause sometimes happens as a result of someone else’s comments on the painting, and other times when I reach a point that I surprise myself, like oh, I did not know I could do that.

Could you explain how you work with source images? The photographs are not images that you’re copying but rather images that you’re using in some way to create the painting.

Copying is dealing with what photographs look like rather than what they are. I take my source images not only as images that represent something, but also as ever dynamic objects with potential pasts and futures. So I am interested in the relationship between what they show and what they are made of and how they appear to me. I think painting, due to its history, provides a very complex perspective to think about the simultaneity of image and object.

How do you choose the photographs? Specifically for this body of work that you present in this exhibition, you mentioned that you received around 400 scanned covers of Zan-e Rooz?

I tend to choose photographs with subjects that have an uneasy or twisted relationship to the act of representation, through which the medium is being acknowledged. I would like to catch the camera and photographer red-handed and reveal that moment in painting. But this is not always the case and I sometimes choose them intuitively.

Your canvases are massive. Can you talk about the sense of scale in your work?

I like when the size of the painting acknowledges the size and location of the viewer. Depending on where you are located as a viewer, you might miss something in the painting — getting close to see the details you might miss the whole composition, and then stepping back means missing the details. So there is always a sense of an incomplete image through the experience of the painting.

Navigate through Taha Heydari’s Artist Room

Sumac Space is a venue for raising questions and conversations.

It is updated every Thursday with a new, fresh dialogue/text.

Subscribe to the newsletter to be kept up to date.

Davood Madadpoor (b. 1981, Tehran Iran) has worked as a librarian, dealing with archiving methods, and later as office manager in the Tehran Art Center (Hozeh Honari) before he studied photography at the Iranian Photographers’ House and the Tehran University of Applied Sciences and Technology. After moving to Florence in 2013 and received a bachelor’s degree in fine arts from the Accademia di Belle Arti. He then graduated in Curatorial Studies with a master’s thesis focused on the local context as an impetus and inspiration for the art practices of artists-in-residence. He is currently working at Villa Romana, Florence, as assistant curator and project coordinator.