Victoria DeBlassie: Is your current work about ethnobotany and its complex relationship to history and contemporary politics informed by your studies in agriculture at the Hebrew University of Jerusalem in 2007?

Alaa Abu Asad: No. My studies there were not the reason why I was interested in plants, because then I was really looking at plants through an observational lens, as something to be studied, to be looked at; they were passive. Now I’m looking at plants in their active role through history and how they take part in shaping history.

Victoria: When did you start looking at plants differently?

Alaa: When I started working at the Palestinian museum in 2015 – 2016. The museum was preparing for a brochure to give to visitors for an opening ceremony about plants that are endemic to Palestine, growing in its gardens. I was asked to join two professors at the Birzeit University to observe flora in the Palestinian nature. The museum gave us a list of these plants to photograph them, but I was also looking at the topography of the place there and the terrain of the area of the West Bank, which is highly fragmented with roadblocks, military checkpoints, borders and separation in general, which also made me think about plants differently, the fact that we couldn’t find all of them due to the circumstances and limited freedom of movement. There were cut roads, fenced lands that were highly secured and we couldn’t reach some of the plants that were on the list because they were outside of the West Bank, and we were restricted to that area, whereas the museum wanted to include an image of all the Palestinian flora. This made me think about this image of the Palestinian flora, and what it means if you can’t capture all of it, or if you can’t even reach it all. So, from there I started really thinking about plants. But I can tell you something else, that when I came to the Netherlands, I was getting interested in how plants move around the globe, how they travel, whether naturally or relying on human activities. I also got interested in how some become deemed as invasive species, such as the Japanese knotweed.

Victoria: Yes, I was reading about it in your project The Dog Chased its Tail to bite it off, but tell me more.

Alaa: It’s one of the most hated plants in the Netherlands and UK, and it’s very badly represented in the media. I saw this plant for the first time when I was at the Veluwezoom National Park, a place where nature is highly controlled, which makes me think about what nature really is here in this park, or at least the concept of “Dutch nature” and the man-made landscape.

Victoria: Absolutely.

Alaa: Then I was thinking about how the plant came to England and the Netherlands, information which is often missing from the media when talking about the assumed problems of the Japanese knotweed. The plant was brought to the Netherlands in the early 19th-century colonial era by the physician, scientist, and botanist Philipp Franz von Siebold, who sailed to Japan with the support of the Dutch East India Company (VOC), receiving gifts from people for medical treatments. He also collected art, artifacts and botany to bring back to Europe. Once the Empire of Japan discovered he was collecting maps, they were offended, suspicious and kicked him out.

Victoria: Oh so only once they discovered he was collecting maps?

Alaa: Yes, and even accused him of being a Russian spy even though they knew he wasn’t, and they kicked him out because they were so offended. This was the break between the Kingdom of the Netherlands and the Empire of Japan because the Netherlands was the only western country that had a relationship with the Empire of Japan. So, Von Siebold came back to Europe with his collection of plants that he introduced and re-introduced to Europe from Japan. First, he went to Antwerp, Belgium, which at the time was part of the Netherlands, a contested area, so he didn’t feel safe with his plants, so he moved further north to Leiden, a city not far from Rotterdam, where the Japanese knotweed arrived for the first time and was planted. It’s important to note that he only brought a female specimen, which means that all of the Japanese knotweed in Northwest Europe and North America is from the same female specimen that Von Siebold brought, which means the plant has been reproducing itself asexually because it’s enough to have a small piece of about 3-4 millimeters of the root to make a new one. It was also during the time of Queen Victoria, where botany, gardens, and plants were all imperial tools. So, the plant moves from Leiden to London also because this was the ethos of the era, planting and gardening. From there it became a noble plant like hortensia, magnolia, and many of them are prominent in gardens even today. The Japanese knotweed was one of Queen Victoria’s favorite plants, so it got planted in London and beyond London. Only about a 100 years later did it become a problem– in the late 70s. They initially planted it to feed the cattle and around railways to stabilize the ground. However, in the 70s, they discovered that the plant basically presents some challenges to urban structures because its roots can go deep, and break through cement, pavements, it can stay dormant for several years and then wake up unexpectedly, so there was this need to fight the Japanese knotweed after it was spreading everywhere, and it costs a lot of money actually. The plant has appeared in many court cases because economic values of properties in the UK have been decreased or lowered due to the presence of the Japanese knotweed, and even insurance companies wouldn’t insure your property if the Japanese knotweed is around. You can also get fined £2500 if you have the Japanese knotweed around your house or in your house and you don’t treat it etc. etc. So, this fighting urge became a national fight against Japanese knotweed. I have to say that the plant is mainly moving around because of human activities. When building new areas, soil is moved too and that’s how the plant is also spreading. So in green areas in these new neighbourhoods, the first thing that appears is the Japanese knotweed because the soil they brought is “contaminated”. So then, they start to look for methods to get rid of this plant and all of that work costs a lot of money. For instance, they try to cover the soil for like 7 months with a thick layer of black plastic but it doesn’t really help, and the plant regrows anew. Then there is the use of chemicals (glyphosate), which is very toxic, as well as trimming, mowing and pulling the plant out, and pouring boiling water on it. A machine was invented which electrifies the plant! In the Deleuzian/Guattarian understanding, it’s a rhizomatic plant, which means that it doesn’t have one center. So, this acentric underground root system enables it to spread everywhere. If you want to get rid of a tree you can just chop it and you know you have one center and you just need to chop it down and that’s it, whereas the Japanese knotweed doesn’t have a center. So, they needed to be creative about how to deal with this. They invented this machine that electrifies the plant, and this high voltage of electricity goes into the root system to weaken the plant, but it’s also very expensive and minimally effective in treatment. Recently, in the harbor of Rotterdam, heat chambers were erected, where the soil is treated with 60° C to make sure that everything is killed including the Japanese knotweed roots / rhizomes, before it’s moved to other places. The plant is often accused of environmental disasters, while the real problem is human activities, which brought on climate change. This plant is just a strong one, and that’s not her problem! It’s our problem, but no one wants to think of it in that way, but only as a “horror plant”. I therefore started to collect newspapers and articles about this plant. The language used to describe the plant is quite striking, as it includes like invasive, outsider, triffid, uneconomic, but also Asiatic, water-thief, cancer, and gang rape!

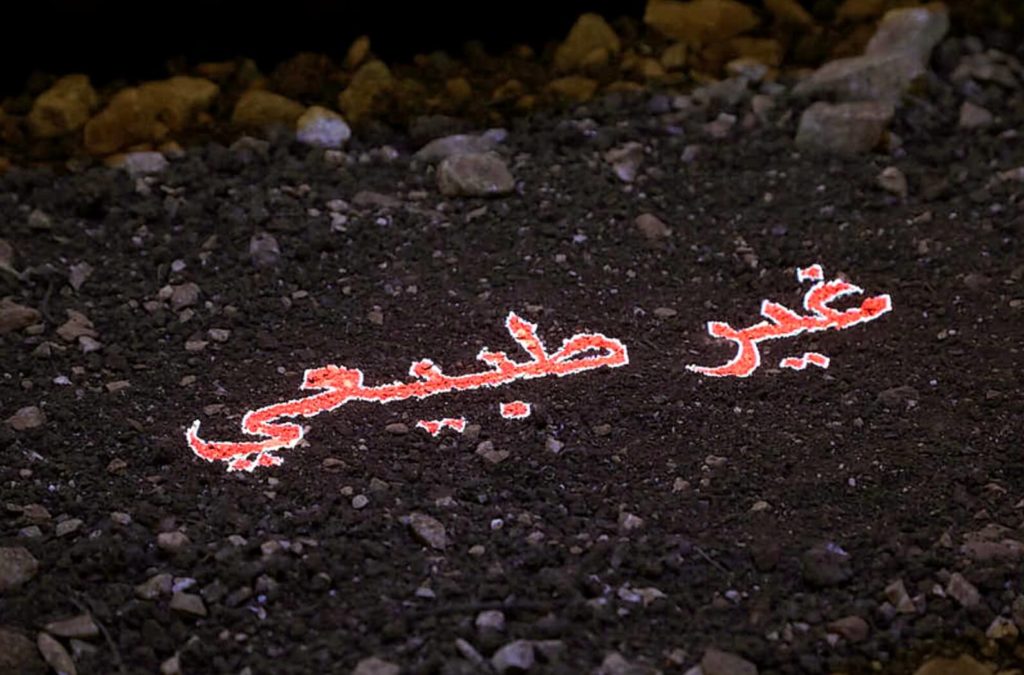

Installation detail: Victorian imperial botany. Working tools, publication and research material, Van Eyck Academy, Maastricht, 2020

Victoria: What? Seriously?

Alaa: Yes, yes! It’s really weird. This language not only strikes me, but also reminds me of the hate xenophobic speech used to describe the human beings immigrating for survival. What I’m saying is that by looking at this plant, I’m trying to show that there’s way more to study about society than the plant itself through the way each place is treating its plants. The way the Dutch and the English are dealing with the Japanese knotweed says a lot about them rather than about the plant. If you look at tulips, for instance, it’s not from the Netherlands, it’s not Dutch, it comes from Iran and Turkey, but it succeeded in becoming one of the national symbols of the country because it has a credit value that brings money to the country, while the Japanese knotweed has a debit value, which means that it costs a lot of money to get rid of it.

Installation detail, Weed Control exhibition, A.M. Qattan Foundation, Ramallah, 2020

Victoria: So, it’s costing them. The interesting thing to me about the Japanese knotweed is thinking about it in terms of like a metaphor for survival and resistance because a lot of societies are against this idea of rhizomatic growth. It’s interesting to think that a plant is actually stronger if it grows horizontally and without a center, instead of vertically. Especially being American, of course in American culture there is the tendency to really value vertical growth and individualism—which I don’t agree with—instead of horizontal growth as if vertical growth is the only way to grow, and that’s the way to become a strong empire or have power. If I were a creative writer I would like to talk about this plant as a way to survive…

Alaa: With its vast roots.

Victoria: Yeah exactly! If you’re growing horizontally, it’s stronger for everybody, I think it’s like a metaphor for being more inclusive.

Alaa: Yes, and recent researchers say that actually the plant is not as threatening to other species as much as claimed. Actually, the only problem with the plant is the urban problem, that it appears in places that they don’t want it to be in. Also, what would make someone invent a machine to electrify a plant rather than just to somehow accept its existence? I don’t think the Japanese knotweed will ever disappear. It’s here and it’s not as dangerous. And why not to think about a symbiotic way of living with the plant instead? Maybe it will be one of the only plants surviving in the future, as we don’t know what the future habitat will look like, as things are constantly changing. Look at us now with lockdowns and Covid and you know it might change even more and more and become more severe. So why don’t we instead somehow embrace the fact that this plant is growing and try to find a way to maybe eat it or do something with it instead of fighting it crazily. I don’t really understand this fear. Many people here when I talk about this plant, they say it’s a monster, but they don’t even know what the plant looks like. This plant is actually useful in other ways, because it blossoms late in autumn and its perfume and flowers attract bees when other plants are dead, which is so valuable. This blindness of nationalism bothers me and in defense of the Japanese knotweed, I think it’s good to think about it in another way.

Victoria: Yes, I think there needs to be a reconsideration for all of its potential. It’s heavy to think about how humans use nature as an attack against other people, to really weaponize plants. I mean this has always been the relationship sadly.

Alaa: Yes, weaponize it, but also foreignize it just as the Japanese knotweed was imported, localized, and then now foreignized again because it’s challenging national acceptance of how plants should behave.

Victoria: Yes, absolutely and I mean it’s curious to think that it was Queen Victoria’s favorite plant and that gardens especially were like a symbol of leisure time, which denotes also a type of economic power.

Alaa: Also, colonial power.

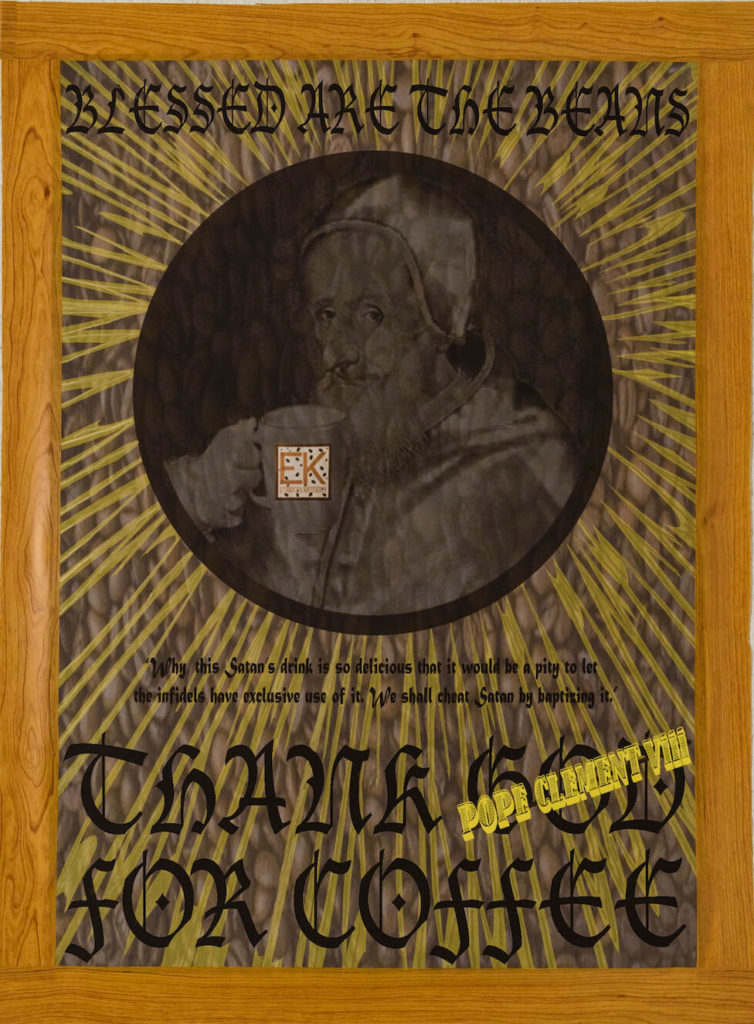

Victoria: Absolutely. I even did a collaborative project a few years ago with the artist Maria Nissan called Interpretation of a Seed about coffee, and I researched all of this history about where it comes from and so you can learn so much about history and colonization and you know why certain things became valuable. Take coffee, for example. It’s not grown in Europe of course, but it still tells us about how botany can trace colonial and domestic power. It basically only became valuable in Europe because it was blessed by Pope Clement VIII because he liked it. Before that, it was considered a devil’s drink of the Arabs and not to be drunk since it was considered lowly, and then when a man in power blessed it and it was no longer sinful.

Alaa: Isn’t it amazing to learn about the involvement of the Royal families on these things or religious figures or the church as well?

Victoria: Yes, it is. It’s like what kind of plants get accepted or not accepted based on certain historical events. Then what’s fascinating is that you know coffee has become so embraced by Italian culture that people think you can only get the right type of coffee in Italy, or, for example, some of my friends thought that coffee was actually a crop grown and produced in Italy, which is in part due to the role of advertising in creating a sense of nationalism because coffee is part of the nationalistic pride of Italy.

Alaa: I think that one of the reasons why it’s easy to attack the Japanese knotweed and to accuse it of so many bad things is just because it’s foreign. For example, the horsetail plant is a European plant that is also very stubborn and problematic. Farmers do hate it but no one talks about it like they do with the Japanese knotweed, and it doesn’t take so much space in the media and advertisements because they just find ways to live with it but not for the Japanese knotweed because it’s Asiatic. It’s also the first thing that you hear in the name Japanese.

Victoria: Yeah and that’s actually what I wanted to elaborate on when I was talking about coffee culture and nationalism or whether plants are either negatively or positively accepted into a country, it still tells the story of nationalism either way and why they’re accepted or not if they’re non-native brought in by various means including colonization, just as the tulips reflect a positive integration only due to economic profit, exposing that something is valuable only if it is financially successful. When I was talking about coffee, I brought it up though too because it became a sort of symbol of Italian national identity really around the time of World War II, because Italy invaded Ethiopia and Eritrea, and so they were able to get coffee cheaper, and during that era Mussolini was trying to create this strong sense of Italian national identity, also by trying and ultimately—thankfully—failing to become colonizers, but in his attempts he created Italian symbols that have stayed until today. Even, for example, the Vespa and the Italian Moka pot that are still huge national symbols today, came from that period also because they were made from aluminum and native to Italy. Then as Ethiopia and Eritrea became colonies and therefore a territory of Italy in Mussolini’s mind, coffee was marketed more as Italian even though it originally came from the colonies.

Alaa: It’s the same with chocolate and Belgium.

Victoria: Yes, exactly. I have an ongoing project that talks about the cultural importance of citrus in Italian history and in the Italian Renaissance; the Medici constructed a new type of greenhouse architecture called the limonaia just to be able to keep citrus alive in a colder climate – harder to grow in without some sort of shelter. Then when France attacked Italy, they took with them the notions of the Italian Renaissance gardens along with the limonaia, and they constructed an even bigger greenhouse for oranges, called the orangerie, that housed other “exotic” plants obtained in questionable ways as well, but after that moment if you were a powerful king in Europe you had to show it by having an orangerie,so this ties back to our previous conversation about how gardens were a demonstration really of power in a very subtle way. You know, it’s interesting just to think that every little thing in life can have this whole colonial, post-colonial and neo-colonial history, that makes me question how we live with ourselves.

Alaa: I think this is where we are today. There is a tendency to depoliticize things which makes people take things for granted without questioning them, but I think we should do it the other way around. That’s the role of art actually, and that’s where art can impact or leave a trace––when art tries to make people think deeply about things, giving them a different image rather than a seemingly neutral one. I think, let’s share things and let’s talk about them and let’s see. Also, time will play a role in this and it doesn’t help if we keep just saying that everything is colonial and everything is bad without doing anything, or at least provide alternatives, or think and work together for better conditions. We should all work together towards a better reality, a better future, and a change. We should do it by working together and speaking to each other.

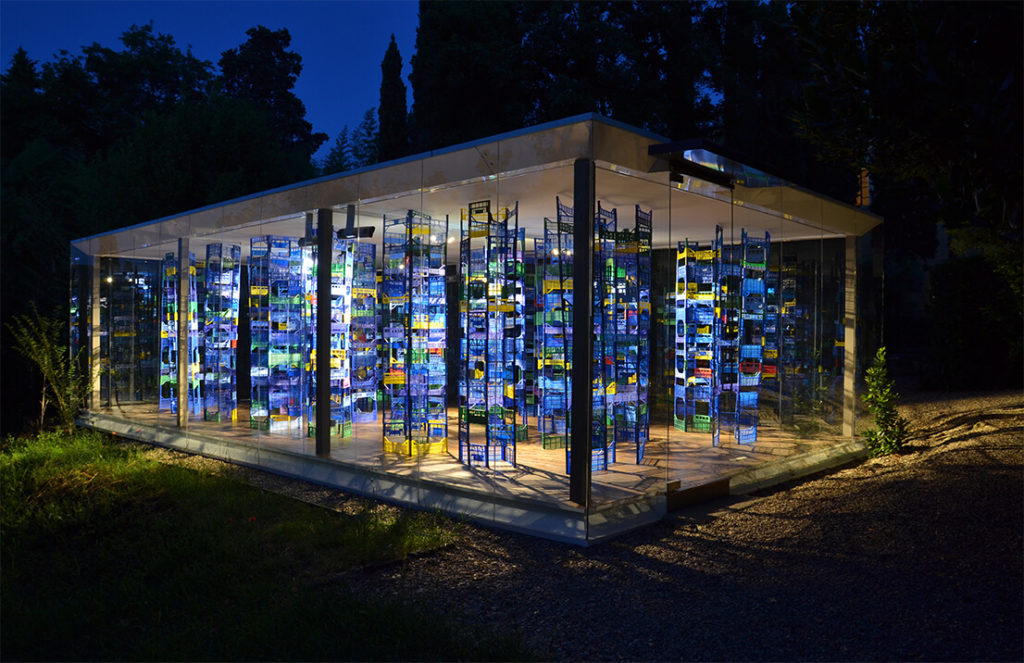

Victoria: I think that obviously we have to slow down and rethink things because of the climate crisis, which is a result of us trying to control nature in a way and using it for our benefit only, instead of working as you said more symbiotically, which I also talk about in one of my installations called Plasticaia.

Alaa: We need to revise this relationship with nature, which doesn’t need to be of this beneficial value only. We should be given the time to explore nature (the meaning of the term too) and to decide if we want to be part of it or not. I think we don’t really like that nature is a mystery and is something that we don’t really know, or expect, but at the same time we have a clear image of what nature should be. Again, it’s time we really need and time to see to undo and revise this relationship that we’ve built with nature and with land. We will always be in the need of using land, therefore, we should find sustainable ways of living, producing and consuming. We should be given the freedom to try things as well and not only to receive them.

Victoria: I’m also curious about your older work and the role of photography. I love that you critique the role of the lens and the camera and the overall function of photography in general, and I’m particularly interested in Photowar, and Image: Imagination, Resurrection. Moreover, some say that photographs are objective, but at the same time it’s cropping out certain realities, certain parts of the image that could create a different narrative. It reminds me of our previous conversation about how in our current life generally people tend to focus on one aspect of an object, the product itself, without thinking of its backstory and what it says about contemporary culture. In a way, the lens represents a certain perspective. So, for me, your way of challenging photography is so important, and I find your questions in Photowar about switching the role/power of representation between the colonizer and the colonized particularly riveting.

Alaa: I think there are two things conflated here, which I will try to make clearer. The one of image reproduction, as today you don’t need a camera to reproduce an image, as cell phones can produce high-quality images. That’s one thing. The problem that I think you’re talking about is more about the photographic medium assuming to be egalitarian and neutral, which it’s not. I have been through a crisis with the medium as somebody who was trained to become a photographer, because the understanding behind the camera underlines its presence! It’s a weapon because whoever has the camera can choose what to capture, what to represent, what to keep, what to include and what to exclude/erase, so it’s never a neutral position and that’s my irritation with the medium. I’m not always comfortable behind my camera, photographing people or photographing things knowing this. For a while I couldn’t do it anymore, but now I think I’m in a better situation with this, because it’s important to understand and to acknowledge this problem of the medium. Producing images is producing information, which is more popular today, and many people can do this, but the real question is who owns this produced (photographic) information in the end and who can access this information. I mean it’s my work as a concept but also as a problem. I think that being a Palestinian is also somehow related to this, because Palestine has been represented through images, but we never could have the chance to represent and produce our own image. Also, on top of that, there’s the role of photography through history and in places like Palestine that have been colonized and occupied, and of course it’s not the only place that has gone through this. I think it’s important to be aware of your position, what you’re doing, why and who you’re presenting and representing. I think the moment I hold the camera I already somehow question the power and my position. Then, it’s a question of how to translate this, and all of these problematics into an artwork, by either creating an artwork explicitly talking about it or decentralizing images and the medium of the camera from the artwork. That’s why my recent work is not photography based. When you study photography or video, somehow because you’re not naive anymore and your eyes are so trained, it can be hard to enjoy images like you did before studying, but there’s also something nice about this naive perspective that can enjoy images as they are. Then somehow now I’m trying to find this balance between a trained and enjoyable viewpoint.

Victoria: I think that it’s interesting that you’re talking about decentralizing things, even images.

Alaa: Once, one of my teachers told me that the most important thing to learn is to know that what you’re doing is not the most important thing, because if you think that’s the most important thing, it doesn’t have any meaning anymore. I really owe thanks to this teacher, but what he was saying is just to be open-minded and to accept criticism and to always try to change the way you look at things, to make things better. I think because nature is changing and dynamic, that’s how we should work as well. We should also allow change to happen in our lives and the way we work and in the way we produce art.

Victoria: Yes, yes and then going back to photography, when you were talking about representation, it made me think about Susan Sontag’s On Photography in which she discusses how we live in an era where we have something represented for us, before seeing it ourselves and this creates a lot of assumptions and certain expectation, either positive or negative.

Alaa: The problem is that often the thing which is represented can look way better than reality itself! It happens that captured reality is much better than reality itself. It brings up notions of what reality really is and if it’s even possible to capture it and how we conceive reality as being, etc.

Victoria: This makes me think again about your clever approach to photography in your Photowar project and how you indirectly captured the image of your mom by capturing the reflected image on the LCD screen of her sitting on a sofa.

Alaa: This project was still about this ethical question of photography along with the dichotomy of the colonizer and the colonized. I thought if I want to show my mom, but I can’t photograph her then, I’ll just take a picture of her reflection on the TV screen when it’s off while she’s sitting on the couch. And, of course, everybody has the right not to be photographed because photography can provide information that you can’t control—it’s a kind of a copy of yourself and your existence. I always have this problem even with IDs and passports and how a photograph of you is required.

Victoria: I have a classic question for you: what do you think for you is the relationship between photography and memory or even the construction of memory?

Alaa: I don’t know because I really don’t think about photography anymore to be honest! Photography didn’t invent images because images have always existed as a natural phenomenon, such as a camera obscura creating the image of the outside “reality” as long as there is light, because light is the only necessary factor to create an image. What photography did in the way we know it today through analog forms to contemporary digital forms was that it enabled these moments in time to be fixed on a metal or glass plate and on negative film and paper and today in the digital file. I think it’s a very shallow or cheesy way if you just want to link photography to memory only. For me, photography is more than freezing memory.

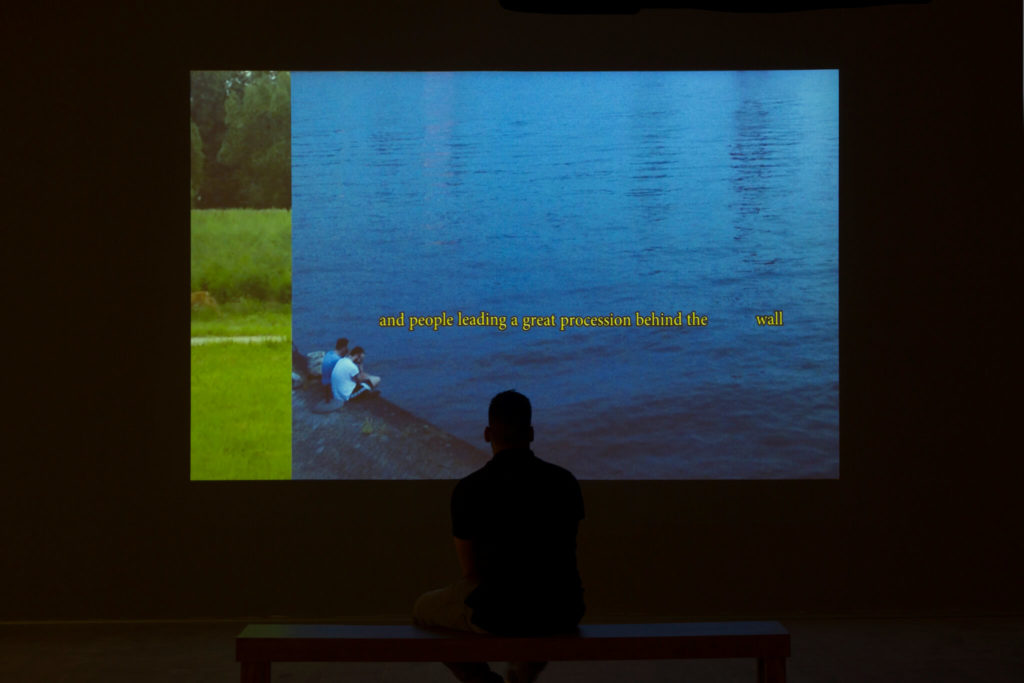

Victoria: I see that you have been using more videos in your artwork recently too. So, for example in The Untranslatable Words of Love I can see your use of translation in relation to the moving image.

Alaa: I was trying to incorporate new things whether it was moving images and translation, or language and image and editing and translation. It was quite important for me to edit the image and the text together in one video. I appreciate what I learned technically from working on this project. In The Untranslatable Words of Love, “مشمش قلبي” in Arabic which is completely different from the English title and is actually one of these untranslatable words or expressions, which means, “the apricot of my heart”. I don’t know an English equivalent for this, but it’s just a way of saying loving things in Arabic. For me it’s about thinking how to translate words/expressions into English without having a literal translation; so, why not put one of these untranslatable words in the title because untranslatability is a field itself, and it’s quite political, as World Literature tends to be able to find a translation for everything, with which I don’t agree. Translation is also political too, like photography, because when you translate things you also imply your own perspective. It’s important to think of the personal and the collective as political, for it’s a matter of juxtaposing moving and still images, together with text, especially when you don’t want the text to work only as subtitles.

Installation view, We Shall Be Monsters (YAYA 2018), Qattan Foundation, Ramallah

Victoria: Speaking of untranslatable things, one of the things I like about living in a foreign country is that I’m fluent in Italian and I can understand it because if I see an English translation of something that’s in Italian, there is so much information left out. What is fascinating to me also is that different cultures have different ways of expressing themselves. Also, when I was studying cultural anthropology at the University of New Mexico, we studied how language is a reflection of culture, surroundings, and cultural beliefs. For example, certain past civilizations didn’t even have a word for snow, and yet in other areas where it snowed heavily, they had different types of words to describe different types of snow. So, language really is a representation of our reality and where you come from. So, I find this work really fascinating and that’s why I wanted to ask about it as well. Did some people find the concept of this work frustrating because not everything can be translated directly?

Alaa: There are not so many words in this work, and it was more about the concept of un/mistranslation. Also, when you were talking, I was thinking about the difference between both written and spoken languages, because they’re completely two different things in Arabic. The dialects we speak are different from the written formal Arabic. So, we have words for certain things but the formal Arabic doesn’t include these words. It’s interesting to look at how people talk in daily life and communicate between themselves.

Alaa Abu Asad is an artist, researcher, and photographer. His practice is centred around developing and experiencing alternative trajectories where values of (re)presentation, translation, viewing, reading, and understanding intersect.

www.alaaabuasad.com

Alaa Abu Asad’s work was presented between 06.04. – 31.07.2019 at philomena+ in Vienna, Austria https://philomena.plus/programme/alaa-abu-asad-1-the-assembly-plants-observation-in-the-urban-sphere/

Victoria DeBlassie is a multidisciplinary artist who recontextualizes discarded objects and materials to suggests the excessiveness of material culture and the human impact on the environment. After receiving her BFA from the University of New Mexico in 2009 and MFA at the California College of the Arts in 2011, DeBlassie was awarded a Fulbright Grant to Italy. DeBlassie has participated in numerous residencies, includingVis à Vis Fuoriluogo 23 (IT),Bridge Art Residency (IT), and Hangar.org (SP). Recent solo exhibitions include Anthropomorphic Cosmesis at Finestreria (IT) and Plasticaia at the Villa Romana (IT). Her latest group selected shows include Per quanto tempo e’ per sempre, Celle Frigo (IT), The Recovery Plan, Fondazione Biagiotti Progetto Arte (IT), as well as two-artists shows including: Trame Plastiche—Bridge (Collaboration with Leonardo Moretti) Vicoli d’Arte (IT); Cenacoli Ombrellìferi (Collaboration with writer Connor Maley), Chille de la Balanza (IT).

Sumac Dialogues is a place for being vocal. Here, authors and artists get together in conversations, interviews, essays and experimental forms of writing. We aim to create a space of exchange, where the published results are often the most visible manifestations of relations, friendships and collaborations built around Sumac Space. If you would like to share a collaboration proposal, please feel free to write us. We warmly invite you to follow us on Instagram and to subscribe to our newsletter and stay connected.