I’d like to start by asking you to reminisce a bit. I think it’s a good way to begin the conversation about your work since it is so strongly revolving around memory. Can you describe the context in which you started making Fragments? What inspired you or moved you in this direction?

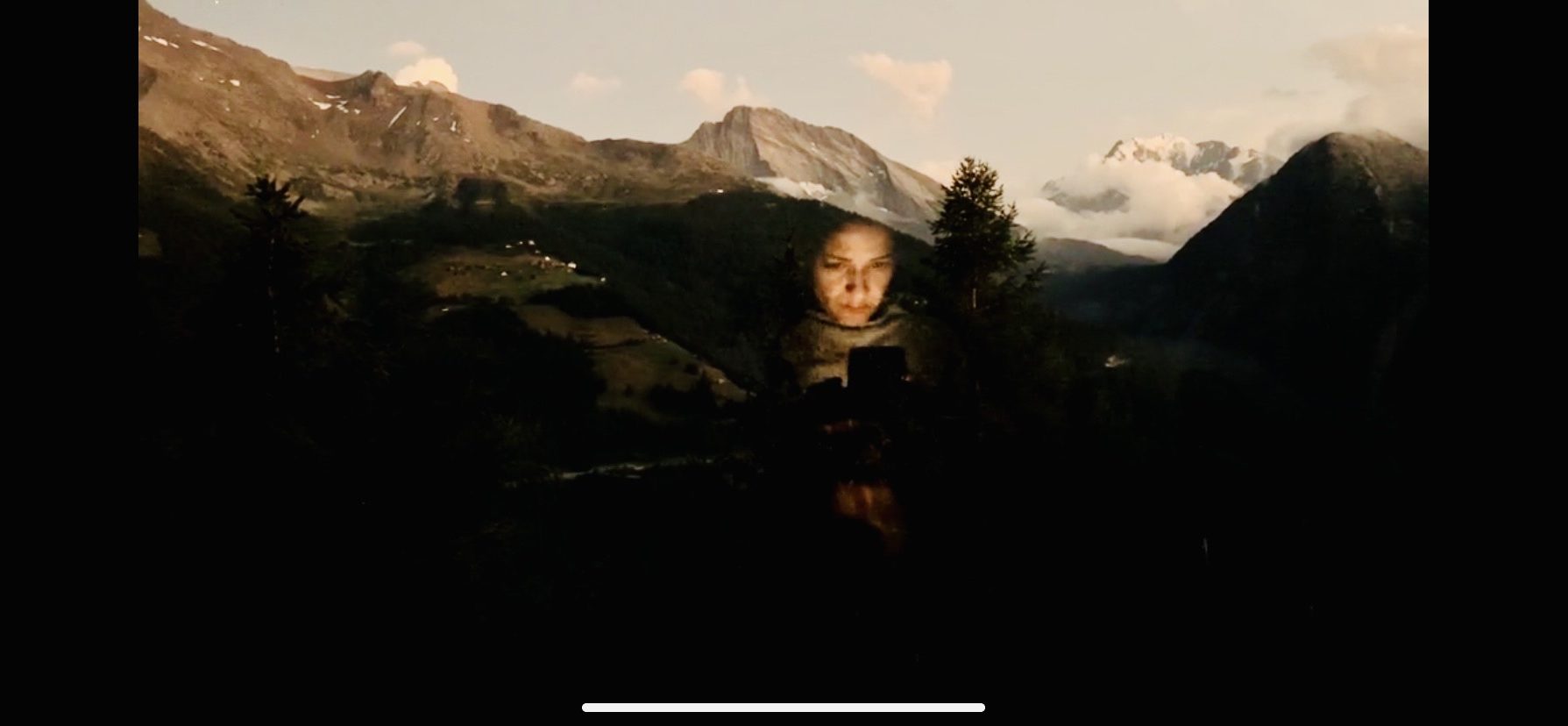

Restrictions and enthusiasm. The idea of the Fragments series was initiated after I made a short film in 2012. I was eager to continue filmmaking, yet I was struggling with time because I have two kids. After my second child was born, I couldn’t allocate personal time to long-term projects and I couldn’t maintain contact with other artists. Despite everything, I decided to embark on this journey but with one condition: not to put myself under stress or impose restrictions. That meant I could not get a hold of special equipment, nor could I commit to teamwork with a crew. All I had was my mobile phone. It has a camera and that was all I needed. I took the first video of this series while I was strolling with my daughter around our neighborhood in Amsterdam. It was autumn and the weather was a bit gloomy but inspiring nonetheless. The whole process is about placing myself and then the audience in an uncertain abstract state, something between delusion, haste, and uneasiness.

What were the incentives and the challenges in the process of making this series of short DIY films?

I was always interested in cinema and filmmaking but it is not easy to make a film all on your own. I had the chance to make a short film with the help of a professional crew here in the Netherlands and Iran, and one animation with the collaboration of some talented artists, but other than that, I was doing everything on my own – script, shooting, editing – when I made a few short documentary films. It might sound difficult but I realized I prefer to work this way which, I have to admit, does limit my options. You don’t have access to other people’s talent and expertise. But as I usually don’t follow a specific, direct plan, it would be difficult to ask someone else to join while I am on a personal journey and the road or the path is not clear to me. Working alone has its limitations but this strategy maintains the private nature of the work I’m trying to create.

Blending different media formats has always been very appealing to me, so this time around, I decided to make a collage with different video pieces under one principle: not to generate a rational idea but to be spontaneous and instinctive. When I shoot, and later while editing, there is no rationale throughout the process; I don’t tend to come up with a hidden meaning for every single shot. I am just relying on uncertain feelings and interpretations. The most gratifying part is editing; I usually have ten to fifteen small video pieces, and then I choose the order and speed in which they will appear. Another motivating part is adding sound, which, I believe, is not interfering with your feelings as obviously and directly as music does, but it adds something very subtle. That is how it all started. The desire for making visual narratives made me use my mobile phone as a tool.

In these videos, you point your iPhone camera at your surroundings, at your everyday, but you edit the recordings in a way that estranges reality and invites introspection and psychoanalytic interpretation. It’s a highly subjective perspective that gives off a sense of detachment or even dissociation. Can you explain what this approach means to you?

I would like to reach a perceptual situation that I normally don’t deal with in my daily life; that is the game that I started to play with myself since the first Fragment. Every hour of the day we are visually being bombarded, massively, through our phones, computers, TV, and so on. And in the end, our feelings are not always natural, we feel disoriented. So, I thought, what if I manipulate this vast ocean of visuals through my own process and reach a state that is not clear but is also a new sense. Being detached and dissociated is a tactic to reach that state, to start anew, to dig into my perceptions, and reach something different. These visual Fragments are my answers to myself; I would like to place myself in a situation in which I feel something that I don’t experience in the mundane world, something uncanny, a feeling that is not clear and thus has no name. These short fragments are a discovery for me. I wanted to immerse myself in this very new situation of feeling and later digging my soul. What do I feel? Fear? Suspense? What is it? I really like having this kind of conversation with myself and later the viewers.

Fragments are the latest in your line of surrealist work. Why do you favor this type of expression?

My answer is in the challenge of deciphering meaning. Surrealism is not direct. It is not leading the viewer to a ready-made insight; on the contrary, it creates a unique abstract atmosphere. I like this uncertainty and the opportunity to discover, being engaged, and being part of the concept by one’s own interpretation.

The editing in the Fragments series is very dynamic. The sequences are very short, and so is each of the videos. Sometimes they are at a higher-than-normal speed or filmed in movement, while walking or driving. Was it a calculated decision to show things in acceleration?

Yes, these Fragments are trying to visually attack the viewer’s senses. To achieve this I referred to my own personality, I’m always in a rush, can’t focus for a long time but, in the end, I want to gain something. This behavior is being reflected in the way I shoot or edit. I love watching long shots in a film, but when I edit a really short moment, I would like to get a filmic confrontation.

It makes me think of how we experience the world via screens – compressed, accelerated, and overwhelmed. Our reality is non-stop scrolling and browsing. We tend to repackage our lives into fragments small enough to fit them into the way things are experienced online. Considering the fact that you used an iPhone to film Fragments, I’m wondering if they were born out of these conditions, of the way we interact with our phones, and the way this shapes our seeing, thinking, and feeling?

That is true. If I didn’t have a smartphone, in my case an iPhone, if I had another kind of camera, the result would have definitely been different. You can have a smartphone everywhere, in any situation, without anyone noticing it, and that ability empowered me to forget any restrictions. The quantity of the films you have increases because you have more space. I have this directive for myself, for the moments that I shoot – the filming shouldn’t go beyond 30 seconds because I know I won’t use longer recordings. And it’s all because we are constantly using our phones, recording anything we find “interesting“ and in the end, we have a pile of junk images and videos that we will forget ever even existed. Smartphones are replacing our minds and eyes. This madness, this chaos, and daily visual bombardment definitely affected me as well, and the Fragments is a result of it. All the quick movements of the camera, the fast speed pieces, are the outcome of the smartphone era and the visual onslaught. I also use social media every day, consequently, that has a big impact on how I see the world and the way I want to create and respond. But if I had a bigger camera, the kind that we used to have while studying documentary filmmaking, the situation would have been different. With those chunky cameras, my movements were limited, I knew I had to be very careful about what I’m filming, not wasting time, and films, and thinking in advance. With a mobile phone, you record a lot and if you don’t like it, you simply delete it at once. It’s kind of like garbage for our eyes and of course minds, but that’s the kind of game I want to play through this visual anarchy.

In this sense, it is somewhat surprising to hear poetry classics in one of your videos; they require a very different sensibility and a slower pace of consumption. What role does poetry play in this video series, and in your art- and filmmaking?

From the time I started studying art, poetry has been my main source of inspiration. I don’t think I would’ve been able to start this process without being motivated by it. To me, poetry is the goddess of all forms of art. Even though I don’t read poems as much as I used to, I still carry all those poems I read throughout all these years with me. They’ve been carved into my soul. I immediately connect with any content with the slightest reference to poetry – a film, a painting, or anything particular. In that particular video, I was eager to perceive and experiment the existence of poems following the visuals.

Some of the recurring topics in your work are home and yearning for home, displacement and the confusion of being uprooted, family relations, and memories of Tehran. How do you situate Fragments in regards to these topics and your older pieces?

The series I did before, related to the topics mentioned, was started when I moved to the Netherlands. I was living in a small city in the north of the country. It was a sort of a cultural shock to me and I felt very isolated. That’s when I became creative, to express what I was going through. During that time, my main concern was displacement and a form of self-imposed exile. But gradually, I moved on and started to live in the present. Fragments are the result of longing to live in the moment.

Navigate through Parisa Aminolahi’s Artist Room

Sumac Space is a venue for raising questions and conversations.

It is updated regularly with new, fresh content.

Subscribe to the newsletter to be kept up to date.

Adela Lovric is a Berlin-based cultural journalist, curator, and producer. Her research focuses on the representations of migration and counter-narratives in film and video art. Currently, she is working as part of several institutional and independent collectives, developing publishing projects, producing events, and experimenting with curatorial strategies.