Sumac Dialogues is a place for being vocal. Here, authors and artists get together in conversations, interviews, essays and experimental forms of writing. We aim to create a space of exchange, where the published results are often the most visible manifestations of relations, friendships and collaborations built around Sumac Space. If you would like to share a collaboration proposal, please feel free to write us. We warmly invite you to follow us on Instagram and to subscribe to our newsletter and stay connected.

Milad Odabaei: Parham, the images of Asymmetrical Authority are at once familiar and strange to the imagination imprinted with the political history of contemporary Iran. They recall the 1979 Revolution that deposed the Pahlavi monarchy and brought about the Islamic Republic as well as the eight years of war with Iraq (1980-88) that immediately followed. But the colors, folds, shapes, and cuts that give form to your photographs make the familiar a bit strange. Can you tell us about the images?

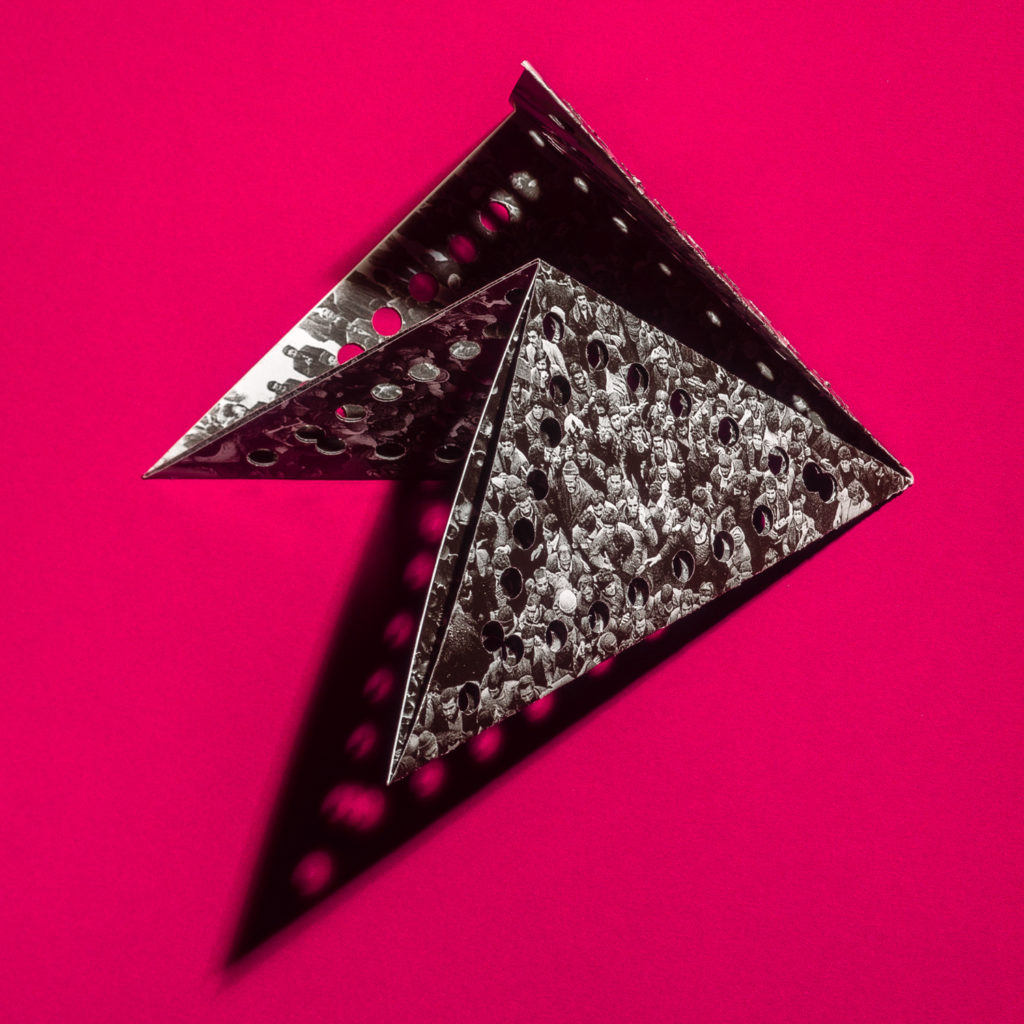

Parham Taghioff: As you know I was born just a couple of months before the Revolution. Like yours, my childhood memories are of a highly uncertain and extreme ideological atmosphere of the post-revolutionary decade during the war. During those years I developed a game with my grandfather. I would wait for him to read the newspaper, which I remember him doing with an extremely worrisome and disheartened look on his face. We would then play with the paper, fold it, cut it, and make it into different shapes and forms. This was the origin of Asymmetrical Authority, and really, all of my experimentations with history and image. In my game, the documented history of the earlier generations’ struggles and achievements, became the raw material for creation. Today, over three decades later, I have started a new game with the similar images of the past but, this time, as an author.

In the last few years many books of documentary photographs have been published in Iran. Books, for example, of the archival news images of the Revolution or the Iran-Iraq War. A noteworthy example is a book modeled on the 2002 volume “Century: One Hundred Years of Human Progress, Regression, Suffering, and Hope” published by Phaidon (London and New York). The history of these books goes back to the publications of bilingual, English and Persian, books of documentary images of the war. Three decades later, these books still serve various ideological purposes and reproduce orthodox narratives of our lived history of the Revolution and the war. They emphasize, for example, the popularity of the Revolution or that the war was internationally imposed on Iran and the Iranian response was a “holy defense.” [The war with Iraq is often referred to as jang-e tahmili (“the imposed war”), and defa-e moqadas (“the holly defense”) in Iran.]

The sources of my images are drawn from such books and similar archives of Iranian documentary and news photography. In our time when an academic and critical interpretation of photography is not entirely accessible to the general public, rapid reproduction and circulation of images provide answers to difficult historical predicaments. Images, along with other forms of easily accessible information, function as an authoritative source and dispel other forms of interpretations. In Asymmetrical Authority, I have reproduced historical images but have tried to empty them of their signification and excavate other possible interpretations.

Milad: In what you are saying I hear echoes of not only critical reflection on art and modern reproducibility, but also post-revolutionary Iranian debate on national historiography. Asymmetrical Authority, it seems to me, breaks with the doxas of both leftist and Islamic narratives of the Islam and the Revolution and poses national (meli) history and historiography as an unresolved problematic in the form of a question. Can you speak about the capacity of photography to confront a political world saturated with ideology and myth? How do you mobilize photography for critical historiographic exploration?

Parham: Transforming our understanding of time, the camera has the capacity to challenge our understanding of the past. Through reproduction, as Walter Benjamin notes, photography undermines the authority of the original and the sanctity of the author. Popularization of photography has enabled everyone to confront the world through the mechanical or digital eyes of the camera, and to tie together being and time in a click. Citizen journalists, with the capacity of both capturing and circulating “the news,” have challenged the monopoly of traditional news makers as well as the national and international jurisdictions of traditional journalism. Today, news media often follows the images that appear on social media by lay image-makers.

At the same time, however, the sheer volume of the images in our daily lives diminishes our capacity to discern the historicity of the past. Everyone has acquired the power to establish the meaning of images and by extension, the meaning of history. Digital photography challenges traditional regimes of citationality, facticity, and authority and instead, emphasizes discursivity. Today, more than ever, the meaning and significance of images are established in the context of their circulation and reception. The truth of images, in other words, lies beyond their genealogy in a particular time and place. The question is how we locate images in historical narratives and memories, and how do we draw on living images to tie together the past, the present, and the future. In her book On Photography, Susan Sontag emphasizes an important point: “Cameras are the antidote and the disease, a means of appropriating reality and a means of making it obsolete.”

Milad: The tension between traditional and professional forms of authority on the one hand, and democratic authority as well as populist dissolution of authority on the other, is central here. Can you speak about the title of the collection, Asymmetrical Authority?

Parham: When I started to work on this collection I came across an article by Lutz Koepnick titled “Photographs and Memories”. I found a deep resonance between what I was doing to the images of the past in the studio and Koepnick’s attention to time and history in photography. Koepnick draws on Sontag and her Wittgensteinian approach to photography to move beyond a purely representational analysis of photography. He writes:

The most essential question is therefore not how different technological inventions cause different representations of temporality, but how we place certain images—digital or analog—in larger narratives of history and memory; how we make use of both their formal inventory and exhibition in order to connect different pasts and presents; how we rely on different strategies of naming, description and inscription, of discursive en-framing, in order to infuse them with temporal texture or pass them off as souvenirs of frozen time; and last but not least, how we engage older myths of reference, objectivity, and truth in order to define the relationships between image-makers, photographic subjects, and viewers as relationships of either asymmetrical authority or mutual recognition. No image, whether computer-processed or not, has an existence or memory of its own. It is what we do with them that decides over their life and afterlife. It is how we situate them against the backdrop of other narratives, discourses, images, and strategies of representation that enables them to speak in various ways about the past and its bearing on the present. [Citation: Koepnick, Lutz. “Photographs and Memories.” South Central Review 21.1 (Spring 2004): 94-129.]

My photographic practice tries to confront the force of technological representation and reproduction and explore possibilities of creative intervention.

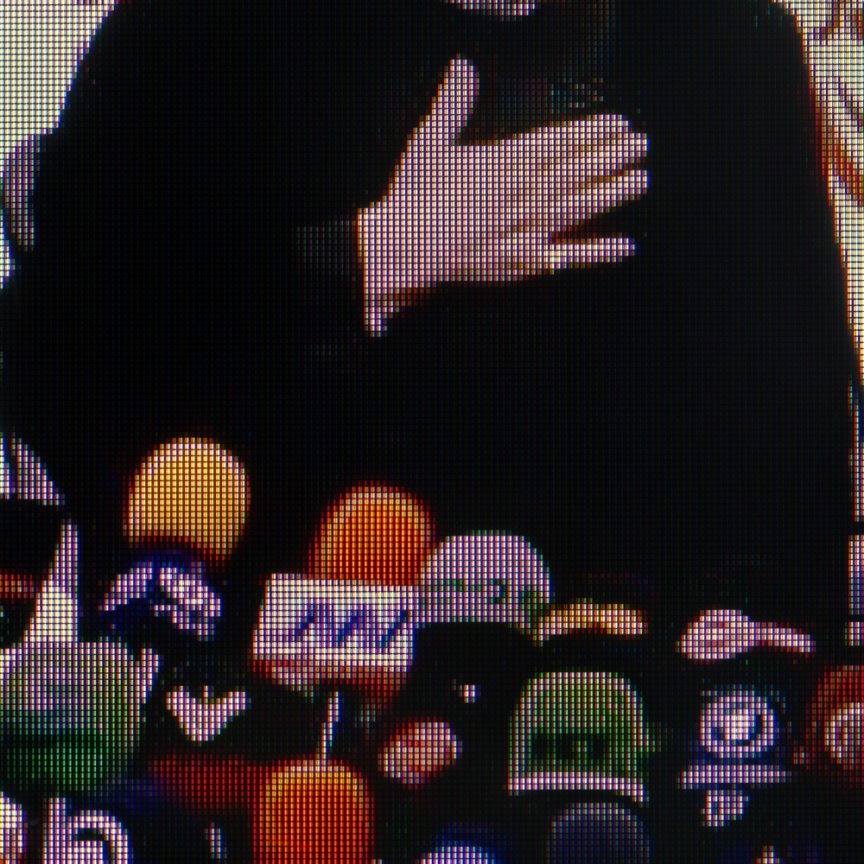

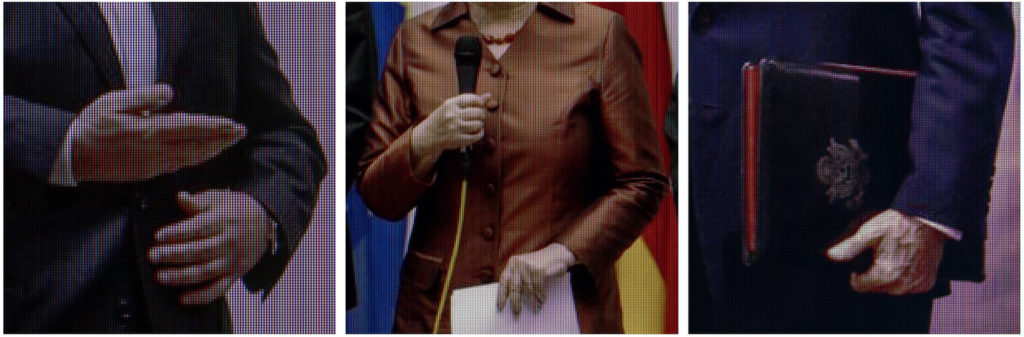

Milad: Central to questioning of authority is a kind of distancing. Asymmetric Authority, and your previous collections that it builds upon, all perform a form of photographic distancing. Let’s talk about your last collection, Hands On Hands Off, which was produced in 2014 at the height of negotiations between Iran and the G5+1 over Iran’s nuclear program, you produced images of hands and gestures of politicians who were negotiating the fate of the deal and with it, supposedly our collective existence. Can you address your use of distancing, zooming in and out, and what it achieves technically and otherwise?

Parham: During the negotiations between Iran and the G5+1 we were experiencing a very complex situation. Any exchange between the two sides had a direct effect on our lives, not simply socioeconomically, in terms of easing of economic sanctions, but also politically. The international negotiations were deeply tied to highly divisive domestic political contestations. The images of negotiations saturated the Iranian and international news. For the first time after the Revolution, the foreign ministers of Iran and the United States were part of the same conversations, along with other G5 leaders and Germany. In these images the gestures of politicians had attracted my attention. Under the attentive gaze of the camera, the bodily gestures of politicians provided the disempowered viewer with important information. Using a macro lens, I focused on the news media images of the negotiations and reproduced the gestures of politicians as they appeared on the camera monitor. Printing the result in large frames, I then challenged the viewer ability to discern the representational content of the image in the exhibition. In close proximity, the viewer would only be able to see the LEDs lighting behind the image. He or she would have to step back to be able to see the image. My aim was to create a theatre of my own, and through techniques of separation, combination, magnification and rearrangement, bring to the viewer’s awareness the work of power in news media and in the mediation of our lives.

How do you think of your images as working within and against a national imagination? How do you think the reception of your photographic response to the Revolution and the war is generationally mediated?

We all have different imagination of our respective national identities. But are all born into particular histories. We might think that what has happened in the past is in the past and unchangeable. But every historical examination shows of a different image of the past, and as a result, the past, the present, and the future are reconfigured anew. Iranian national ideology is largely steeped in myth and ideology. In my opinion, we urgently need to pose new questions of our pasts and develop our engagement with the images of our history toward critical cultural and historical studies.

Indeed, Asymmetrical Authority has received different responses from our generation and those before and after us. But history, perhaps in a Hegelian sense, is the synthesis of different and at times conflicting interpretations and pursuits and irreducible to any one account or project.

Milad Odabaei is a postdoctoral research fellow at Princeton University. His research brings together anthropological and critical methods for the study of modern Iran.