As a Palestinian female artist, you are living in Haifa, which is today part of the state of Israel, a country that even denies the existence of Palestine as such. What role does your own identity play in your artistic practice?

When I decided to be an artist, it was way of finding a place in the world I live in. I was searching for a place where it is possible to express myself and have an audience. I deal with identity struggles, struggles I face as a women in a patriarchal society as well as a Palestinian living in Israel.

Identifying as a Palestinian in the Israeli context is often perceived as a negation of the existence of the state of Israel and is met with incomprehension. Introducing myself as a Palestinian and simultaneously stating Israel as my country of residence goes beyond the predominant logic. In order to affirm my existence, I turned towards contemporary art. Through my artistic practice, I have found a way to deal with my own political identity, tackle issues that are relevant in this context and try to make a change.

Your work فرز (in English: to separate, to isolate), which is presented in the exhibition Present imperfect here at Sumac Space, deals with the remains of former Palestinian houses in the neighborhood Wadi Salib in Haifa. With cautious dedication you clean every single stone that you have picked up from the ground, as an act against a fall into oblivion. May I ask you to elaborate a bit on your own relation to the city of Haifa and the story behind your project?

Haifa is the city where I currently live and work, and I feel very connected to it. It is a historical Palestinian city. It’s a harbor city and has an important historical market. And even after 1948, it has continued to be an important city that has attracted young generations of Palestinians. Today it is considered to be the cultural center of historic Palestine, where many political and cultural movements were established.

The work فرز digs deeper into the history of one neighborhood in Haifa. It looks into the remains of houses of those Palestinians who were forced to leave their homes from one day to another and tells an often-untold story, which the Palestinian author Ghassan Kanafani also refers to in his novel Return to Haifa (1970). In this book a couple was kicked out of their house, deported out of Palestine, and even had to leave their baby behind. They were forced to leave their home in 1948, and in 1967 when they were allowed to come back for a visit, they see their son again, who was raised by the Jewish immigrants living in their home.

I first read that book when I was about 14 years old and perceived it as a tragic story of a family that was torn apart. Now, almost 20 years later, I am going back to this novel, seeing it in its historical and political context and relating to it through my art.

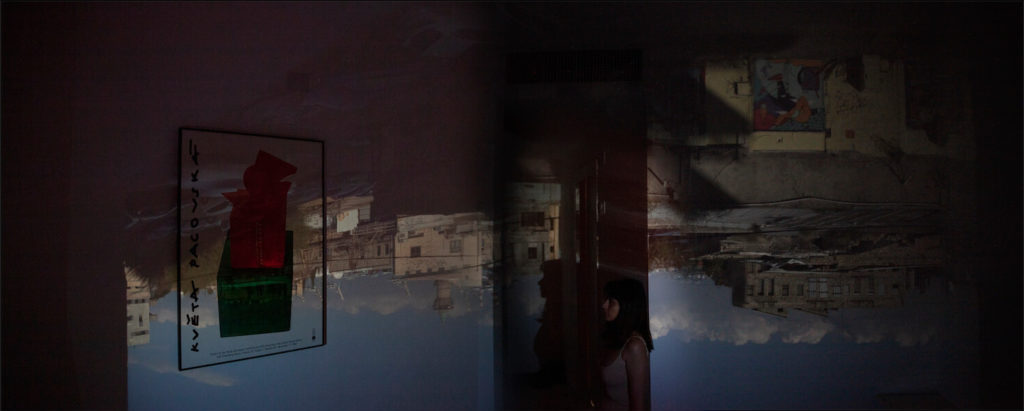

Wadi Salib is one of the neighborhoods that was affected. In 1948 the Palestinian population was expelled from their own homes. Today, it is a neighborhood that has been totally renovated; new housing complexes are built and the establishment of an artist village will accelerate the gentrification process. The video work فرز looks back on the neighborhood’s history and attentively gathers evidence of its tragic history.

After working on it, I see the neighborhood with different eyes. It became not only my own neighborhood as I live here right now, but also a research topic where each stone tells a story and catches my interest.

After watching your video works فرز and 531 times, the repetitive, even meditative, actions that both have in common stand out. What role does repetition play in your work in general?

Repetition plays indeed an important role in several of my works. You have cited 531 times and فرز. The video piece 01:41 can also be added to the list.

In political discussions I often find myself confronted with the necessity to explain the same issues again and again. It feels like being stuck in a loop. Instead overcoming the problem and learning from it, the same problem has to be faced again and again, similar to Sisyphus in ancient Greek mythology.

My video works 531 times and 01:41 refer to the ongoing Palestinian struggle, the situation of being stuck in a loop, of having to repeat a claim for existence again and again.

531 times portrays a woman sifting flour 531 times, the number of Palestinian villages that were evacuated in 1948. It is also the first video in which I am in front of the camera. Actually, I filmed it first with different people. Every time something had to be adjusted: the lighting, the position of the camera. As nobody wanted to do it again, I finally found myself in front of the camera. As the video evolves, the pile of flour becomes a triangular shape that enters the space – a phallic form that refers to political topics such as occupation or patriarchy. The title 01:41 also references a historical number: the 1.4 million Palestinians who were deported in 1948. In a single frame setting, a man shifts blank papers from one side of the desk to the other side.

References to numbers and dates as well as repetition are quite subtle ways to tackle complex political issues such as occupation or expulsion. I would like to come back to the neighborhood Wadi Salib in Haifa and your two-channel video Talqit 2’46’’ that links it with Daliat el Carmel, the place where you grew up. What was the idea behind linking these two places?

The video piece تلقيط (in English: to take, to pick up, to collect) is a two-channel video which shows on one channel myself picking up stones of demolished houses in Wadi Salib in Haifa and on the second channel it presents my aunt who is collecting the plants za’atar (زعتر) and akoub ( عكوب) from the ground in the surrounding area of our village Daliet el Carmel. In early 2020 I was wandering around the forest of the Carmel mountain together with my aunt and just had the idea of filming her in this scene. Later on, I decided to combine the two scenes as the actions, movements and even the meaning fit together.

In the ongoing renovation project, the city follows the claim to preserve the abandoned houses in Wadi Salib – but of course without acknowledging its history. In that sense the confrontation with the neighborhood’s history is endangered and so are these plants. Until 2018 they were classified as endangered plants and it was even forbidden to collect them. In that sense, both of us, me and my aunt, perform the same action – picking up things from the ground and collecting them so as to not fall into oblivion.

On another level this video piece is a discussion about where I come from and looks deeper into the family story. While my close family is very political and position themselves openly as Palestinians, the people in my village as well as my extended family belong to the Muslim spiritual group of the Druze, who were able to stay in their village because, historically, they presented themselves as loyal to Israel. Combining the two scenes in the video تلقيــط also reflects the complexity of the political history and situation within the Israeli–Palestinian context.

Coming back to your references and artistic influences, in your artist’s room here at Sumac Space we can see Shirin Neshat’s and Chantal Akerman’s works presented alongside a selection of your own works. How do you relate to these two artists and what role do they play in the development of your own artistic practice?

When I was putting together the content for the artist’s room, I decided to include my inspirations and references. I thought of this space more as an experimental platform, so I wanted this space to be something more experimental, instead of being a simple portfolio of my work. At first, I had a lot more references in mind; Shirin Neshat and Chantal Akerman finally made the cut.

Shirin Neshat’s work has an influence on my practice on a very personal level. The act of liberation that is inherent in her photographs and video works is something I can relate to. As an artist it’s this kind of feminist approach that is important for me.

In another way, I relate to Chantal Akerman’s movie Jeanne Dielman, 23, quad du commerce, 1080 Bruxelles (1975…), which influenced my work on a formal level. One of the scenes in the movie portrays a woman during the act of cooking; without any cuts the video documents the whole process. In a very subtle way she also deals with the daily struggles of a woman. Someone once described her work very pointedly: “Inside the calmness, there is a storm happening.“

What a powerful sentence! In my opinion, this also relates a lot to your art works, which explore political and historical issues through a very poetic and often repetitive aesthetic. They share this calmness and are yet full of societal references

Navigate through Jafra Abu Zoulouf’s Artist Room

Sumac Space is a venue for raising questions and conversations.

It is updated regularly with new, fresh content.

Subscribe to the newsletter to be kept up to date.

Aline Lenzhofer is an art worker and curator based in Vienna with a focus on artistic practices from the WANA region, on socio-political topics and on collaborative projects. With a background in cultural and social anthropology and a degree in cultural management, she has worked with different cultural institutions in Morocco, Egypt and France and is currently part of the team of philomena+ and das weisse haus, two independent art spaces in Vienna.