Sumac Dialogues is a place for being vocal. Here, authors and artists come together in conversations, interviews, essays, and experimental forms of writing. It is a textual space to navigate the art practices of West Asia and its diasporas which emphasize critical thinking in art. If you have a collaboration proposal or an idea for contribution, we’d be happy to discuss it. Meanwhile, subscribe to our newsletter and be part of a connected network.

The text will be published in Italian in the upcoming issue of Arabpop—Contemporary Arab Arts and Literature magazine.

Wafa Hourani’s work does not just imagine futures: it builds them, piece by piece, often in miniature. Born in 1979 in Hebron, Palestine, Hourani grew up as one of 21 siblings in a refugee household shaped by displacement and history. His art crosses boundaries—sculpture, photography, poetry, painting, film, and sound—but at its core is the act of building worlds: not imagined escapes, but worlds rooted in present conflict, shaped by both personal loss and shared memory. He works at the edges of perception: between physics and poetry, memory and myth, war and imagination. Based in Ramallah, in the occupied West Bank, his work holds the contradictions of life under occupation without reducing them to slogans.

Hourani believes fiction can tell the truth in ways reality cannot. In his work, different pieces come together to create scenes that are both real and unreal. A flower might become a fighter jet. A gun might contain an impressionist landscape. The medium matters less than the method: rearranging what already exists to show what else could. His approach is deeply tied to science; not in terms of data, but in the urge to understand how things relate. Quantum physics, superposition, and systems theory all influence his visual logic. He draws from math as easily as from myth.

Wafa Hourani builds futures that are political, personal, and unfinished—not to offer answers, but to make space for new ones. He does not make art to explain Palestine to the world. He makes art that asks the world to look at how it describes itself. His art does not close stories; it opens them. Through layers and contradictions, he creates new ways of feeling: a world that has not arrived yet.

Cinema Dunia once was a vibrant cultural space in Ramallah, hosting events from screening Cecil B. DeMille’s Samson and Delilah to jazz concerts and bodybuilding competitions. It was a central gathering place that attracted audiences not only from Ramallah itself but also from nearby Al-Bireh, Jerusalem, and surrounding villages. This rich mix of cultural programming made Dunia a unique place of collective experience. However, its life was disrupted during the First Intifada in 1987, when Palestinian chose to close down cinemas as a strategic decision to prioritise resistance over entertainment. The building was eventually demolished, its land first converted into a parking lot and now replaced by a commercial tower housing international fast-food chains, marking a stark shift from a communal cultural space to a site of global consumerism.1

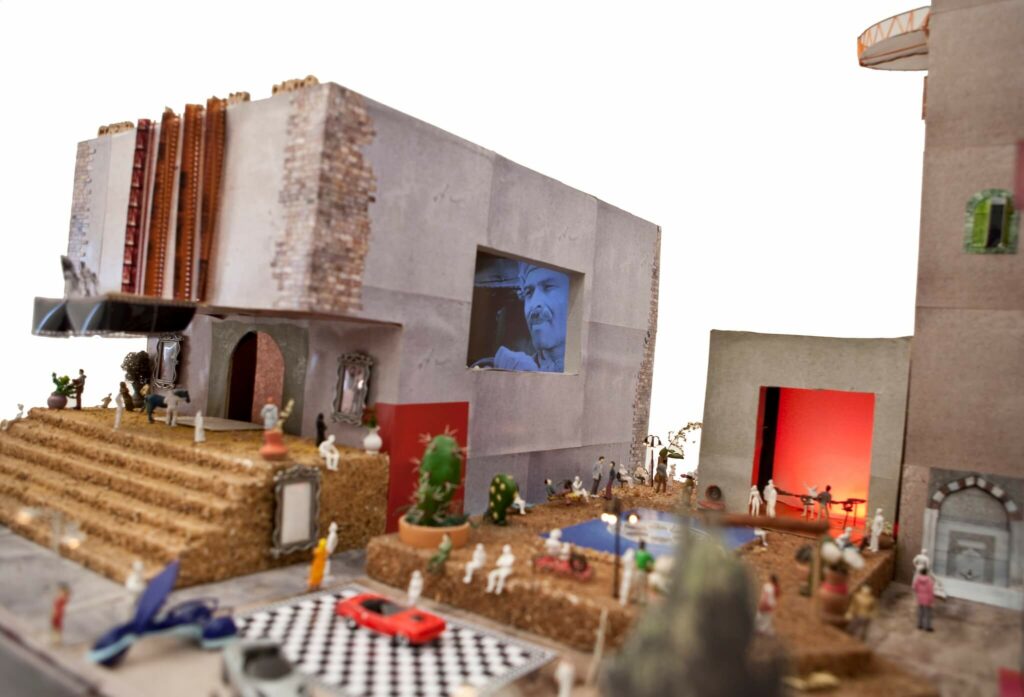

Wafa Hourani’s artwork, a meticulously crafted model of Cinema Dunia, is far more than a miniature replica of a demolished building. Inside the model, he places Mirror Garden, an imaginative public plaza where viewers confront their reflection; mirrors here function politically (the Mirror Party) as a way to make social accountability visible and to prod internal critique and resistance to external occupation. Cinema Dunia is a dense, layered object that functions as a site of political critique, a vessel for collective memory, and a trigger for the imagination. He also reads Dunia’s closure as an internally driven rupture in Palestinian cinematic life. He stages this loss in the model through an 11-minute looped montage of Palestinian fiction fragments, which gestures toward the archive’s unrealised potential. Still, in The Historical Timeline of Qalandia 1948-2087, he refuses total erasure: Cinema Dunia endures in his future narrative, folded into the Mirror Party timeline where walls become mirror-surfaces and the site is repurposed as a space for reflection and political imagination.2

Hourani’s Cinema Dunia operates at the intersection of two poles, simultaneously critiquing the world’s desire to contain and beautify the Palestinian narrative and extending a profound invitation to reconstruct what has been violently erased poetically.

Susan Stewart, in her work On Longing, argues that the miniature appeals to us because it offers a world over which we can exert total control. It creates a relationship of power where the viewer becomes a giant, a god-like figure gazing down upon a self-contained, manageable universe. From this perspective, Hourani’s Cinema Dunia is a profoundly political and critical object. It takes the painful history of a public place—a history of cultural flourishing, political resistance, closure, and eventual submission to global capitalism—and transforms it into an artefact. The complex reality of cinema is miniaturised into an object that can be displayed in a pristine gallery, observed from a safe distance, and even possessed by a collector. The body of the viewer is necessarily excluded: one cannot enter this cinema, but from a controlled distance one can hear its films. This act of creation is a sharp, implicit critique. Hourani presents the world with what it seems to want: a Palestinian story that is contained, beautiful, and possessible. He grants viewers a sense of mastery over a history they might not truly comprehend, but which enables them to become a tourist of trauma, able to appreciate the form without feeling the full weight of its content.3

However, the work goes beyond Stewart’s lens of control. We should not miss its poetic power, knowing that Wafa´s book of poems might be published soon. At this point one should move to Gaston Bachelard’s The Poetics of Space. For Bachelard, the miniature is not an object of control but a catalyst for reverie. It does not shrink the world; it expands the imagination. He posits that a small object, when contemplated, can unlock a universe of intimate immensity. From this vantage point, Hourani’s Cinema Dunia is not a contained object, but an explosive one. It is a machine for generating daydreams.4

Looking at the model in 1 x 2 x 1.7m scale, the viewer’s imagination is not subdued but ignited. It invites us to join the vivid life of cinema and its surroundings. We are prompted to inhabit the space mentally, to reconstruct the scenes that the historical fragments describe. The architectural details—the privileged penwar5 seats, the mezzanine, the narrow stage—cease to be mere formal elements and become stages for forgotten human dramas. Hourani populates these stages with figures and Houses: anonymous whites that stand as the audience, coloured characters that mark the people of Ramallah, and houses with varied antennae that double as a critique of mass media and propaganda.

Bachelard’s idea speaks to the power of the human mind, particularly through imagination, to grasp and interact with the world profoundly, going beyond mere perception or scientific understanding: it is not an act of political domination, but one of intimate, tender care. We do not possess the story; we are entrusted with it. The model becomes a sacred space where the ghosts of a community’s past are invited to gather in a future. At the same time it allows for a poetic journey, a way of feeling the immensity of the loss precisely because of the smallness of the object that represents it.

Wafa Hourani’s Cinema Dunia flickers between two states: an object of critique and a receptacle of imagination. It confronts us with our gaze, forcing us to ask whether we are consuming a tragedy or participating in an act of remembrance. It is a statement about how memory is packaged for an external audience, and simultaneously a deeply personal invitation to rebuild a lost world within the vast theatre of the mind. Hourani does not simply mourn a demolished building: for him, Cinema Dunia is still there. He claims that while a physical space can be erased and paved over, the world it once contained—its dreams, its fears, its culture, its life—can be resurrected, immense and powerful, within the quiet confines of a box.

1 Yassin, Inas. 2010. Projection: Three Cinemas in Ramallah & Al-Bireh. Institute for Palestine Studies. https://www.palestine-studies.org/en/node/78362

2 Hourani, Wafa. The Historical Timeline of Qalandia 1948-2087. The Broken Archive. https://www.brokenarchive.org/artist/wafa-hourani

3 Stewart, Susan. On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984

4 Bachelard, Gaston. The Poetics of Space. Translated into Farsi by Maryam Kamali & Mohammad Shirbacheh. Tehran: Roshangaran, 2013

5 The penwar seats, regarded as the most exclusive, were situated in the front balcony. They were reputed to be more comfortable and were enclosed by a modest barrier, resembling private boxes

Born and raised in Tehran, Davood Madadpoor is a Berlin-based curator and photographer. With a background in visual arts and curatorial studies from Florence, his practice explores speculative artistic strategies—particularly fictioning—as ways of reimagining contemporary realities shaped by transition, constraint, and shifting socio-political landscapes. He co-founded Sumac Space, an ongoing project dedicated to contemporary art in West Asia. It develops exhibitions and dialogues that emphasize critical thinking in art practices.