Sumac Dialogues is a place for being vocal. Here, authors and artists come together in conversations, interviews, essays, and experimental forms of writing. It is a textual space to navigate the art practices of West Asia and its diasporas which emphasize critical thinking in art. If you have a collaboration proposal or an idea for contribution, we’d be happy to discuss it. Meanwhile, subscribe to our newsletter and be part of a connected network.

There has always been a peculiar absence in our family’s story, one I often questioned as a child. Why was my father’s birthday never celebrated? It wasn’t until adulthood that I understood why: no one knew the exact date. He was born in 1952 to a peasant family working the fields near Al-Zubair, a city in southern Iraq, but his birth was never officially registered. At first, I found that strange, even unsettling, until I came to realize how common it was in that specific time and place. In rural Iraq during the 1950s, when government offices were scarce, roads were unreliable, and literacy rates were low, many births went unrecorded. All that was passed down was a year and a place, remembered not through official documents but through spoken memory, fragile and perhaps reshaped over time.

According to our family’s oral history, our roots trace back to Al-ʿAmārah in southern Iraq, where our ancestors lived as part of the Marsh Arab community. In the vast wetlands between the Euphrates and Tigris, people built arched reed houses on small islands on water, navigated narrow waterways in canoes, and lived by fishing, herding water buffalo, and farming. My family remained there until the mid-20th century, when, like many others, my grandfather was forced to leave. His departure was part of a broader story: state neglect, class exclusion, and environmental degradation that made rural survival increasingly difficult.

My father’s childhood unfolded during the final years of Iraq’s feudal system, a landholding structure entrenched under the British-backed Hashemite monarchy. This system granted shaikhs (tribal landlords) control over vast agricultural estates. These landlords lived off the labor of peasants, who often retained only 15 to 25 percent of their harvest after paying rent and various fees. It was a structure that kept rural families trapped in cycles of debt and dependency. Attempts at reform were largely superficial, intended to preserve elite power and foreign interests while deepening the struggles of those at the bottom. In places like Al-ʿAmārah, those who resisted were often expelled from their homes, sometimes with such brutality that it cost them their lives. Meanwhile, the region faced an environmental catastrophe. The 1940s brought waves of drought and flooding, broken irrigation canals, and the unpredictable behavior of the rivers.

Pressured by these circumstances, my grandfather abandoned rice cultivation and sought any work he could find to support his family. In the early 1950s, he secured a modest government post and was sent to a remote station near the Kuwaiti border to monitor smuggling routes. The family joined him there, settling in canvas tents in the desert, where isolation shaped their daily lives. There was little to do, and the children could attend school only every other day due to the long journey. My father remembers those years with sadness, shaped by hardship but also by the stillness and strangeness of that life. At times, those feelings never entirely left him, even though their time there was brief.

In 1958, Iraq’s Hashemite monarchy came to a sudden and violent end with a military coup. King Faisal II, only twenty-three, was executed at the al-Rihab Palace alongside members of the royal family. Yet it was Crown Prince ʻAbd al-Ilāh and Prime Minister Nuri al-Saʻid who suffered the most grotesque fates. The Crown Prince’s body was dragged through the streets, hung outside the Ministry of Defense, mutilated, burned, and eventually thrown into the Tigris. Nuri al-Saʻid, captured while fleeing in disguise, dressed as a woman, was shot on the spot. His body, buried hastily, was exhumed the next day and desecrated by an enraged mob. These were more than symbolic acts marking the fall of a regime. They seemed to channel something deeper and more primal: the fury of a long-oppressed, humiliated nation intent on erasing not only its rulers but any trace that the old order might return.

While crowds filled the streets in celebration, my grandfather, like many rural peasants who had suffered under the monarchy, welcomed the revolution with cautious hope. He likely understood the risks but still believed it might bring something better. However, instead of stability, it brought about another job loss and more uncertainty. So, he moved the family to Baghdad, joining thousands of others who were migrating in search of security amid the shifting political order.

As rural migrants arrived in Baghdad, families like ours were often labeled shurūg or shargawiyya—colloquial terms meaning “easterners.” These labels, used by established Baghdadis, marked newcomers from the south as outsiders and reinforced deep-rooted class and regional stigma. Yet many of these migrants were settled in the heart of Baghdad. My family, for example, made their home in the Sarifa slum of Shakiriya, an informal settlement that now stands where Al-Zawraa Park is located today.

Like thousands of others who arrived there with almost nothing, they initially built shelters from woven reed mats, materials brought from the south and traditionally used by the Marsh Arab communities. However, the colder, drier winters in central Iraq quickly showed that these homes were not suitable. Eventually, they turned to the clay-rich soil of Mesopotamia, which could be dried in the sun to form adobe bricks. These reed-and-mud structures became known as ṣarīfa huts, and by the late 1950s, Baghdad had approximately 44,000 of them, accounting for nearly 45 percent of the city’s dwellings. The neighborhoods where harsh conditions prevailed clustered around these huts. There was no running water or proper sanitation, and diseases like dysentery and tuberculosis were common. My father remembers the Shakiriya slums as places where crime and violence were part of daily life, with robberies, shootings, and assaults occurring regularly. Yet despite all this, many migrants still saw the city as a place of relative freedom, where at least they were no longer under the control of the shaikhs.

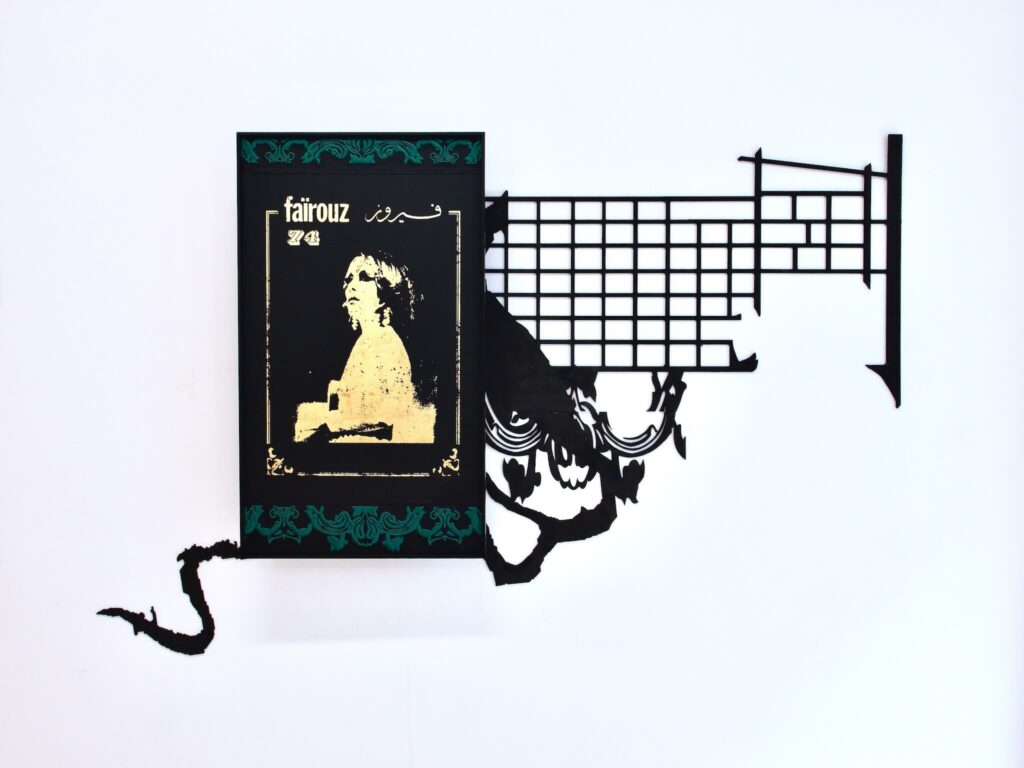

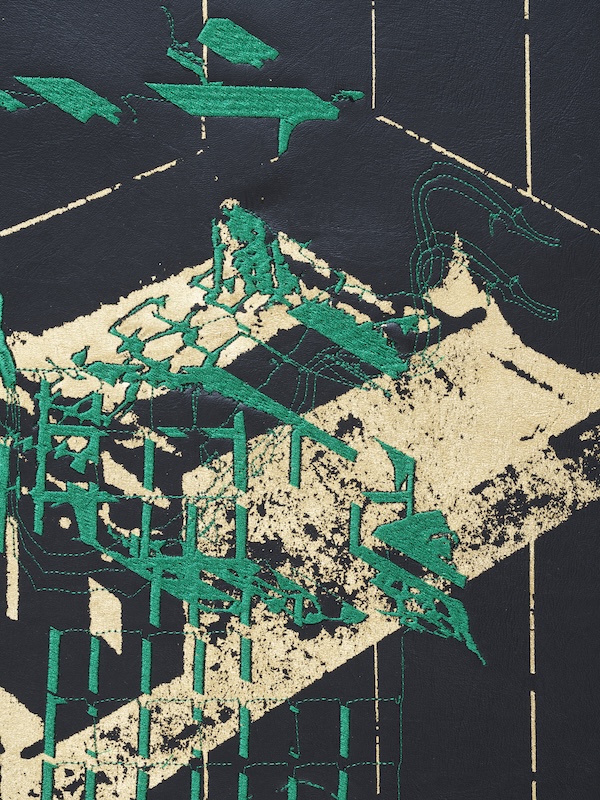

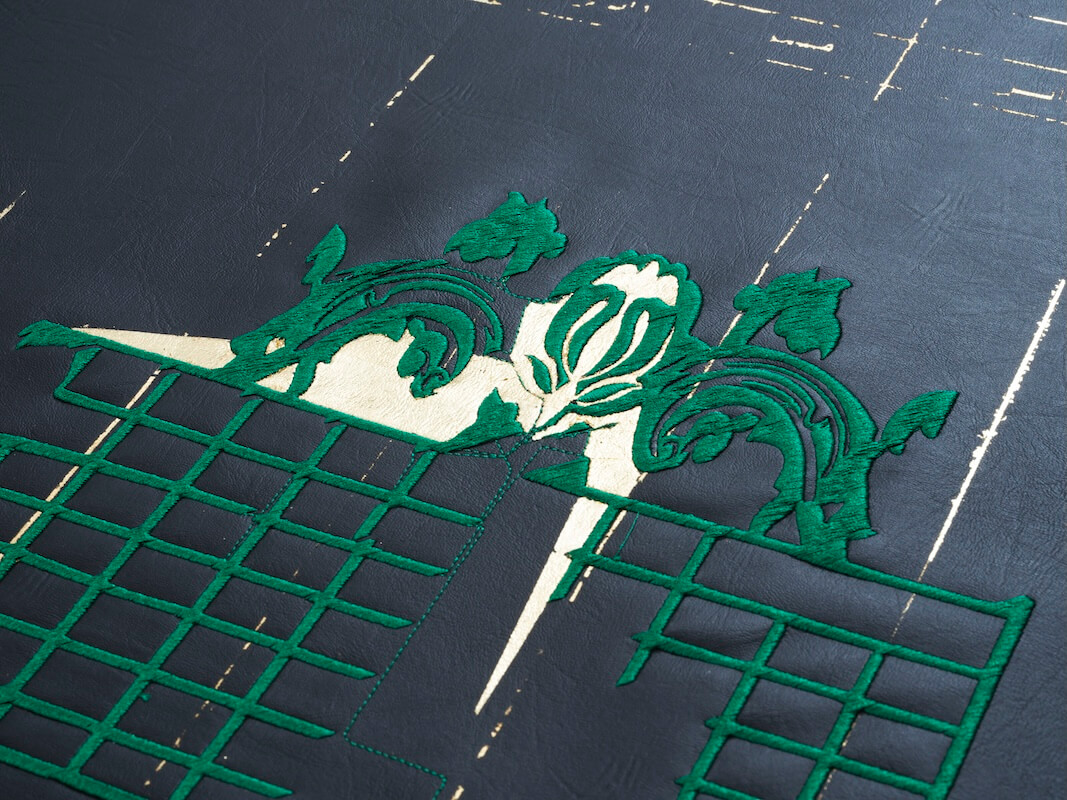

screenprint, golden leaf, embroidery on faux leather

photo: Jaka Babnik, MGLC archive

photo: Jaka Babnik, MGLC archive

In 1963, another rupture reshaped the country. The Baʻath Party, backed by elements within the military and rumored foreign assistance, seized power. Soon afterward, officials forcibly relocated my family, along with thousands of others, to a newly planned suburb on the outskirts of Baghdad. Madinat al-Thawra, or “City of Revolution,” was built. Not only through the state initiative, but also through the labor of the rural, my teenage father, among others, prepared the foundations and laid bricks by hand to construct the family’s modest home. Although the neighborhood was promised as a place of improved living conditions, it still lacked access to basic services. But on top of that, it brought a new layer of hardship: physical distance from the city and a deepening sense of social segregation.

The following years were marked by deepening ideological rifts. By the late 1960s, the Baʻath Party had consolidated its power, and Arab nationalism had become the dominant force in public discourse. Dissent was increasingly silenced. It was in this climate that my father began to form his political identity. His daily routine as a student laid bare the country’s class divisions. Each morning, he walked for hours from the slums of Madinat al-Thawra to the Institute of Fine Arts in the city center. Many of his classmates arrived there by car, dressed in freshly ironed uniforms. The poor, unable to afford such clothes, often rejected them altogether, both out of necessity and as a form of protest. Yet inside the classrooms, these rigid divisions began to soften. Students from diverse backgrounds, including those from wealthy and low-income families, as well as Sunni and Shia, Christian, and Kurdish communities, formed friendships that challenged the hierarchies imposed outside the school walls.

The regime’s escalating violence against the Kurds deepened my father’s disillusionment with the Baʻath Party and led him closer to communism. This was not only a reaction to state repression but also rooted in a more extended history of dispossession in the south. Most residents of Madinat al-Thawra, including my family, had come from southern provinces where generations of neglect and exploitation turned communism into more than an ideology. It became a promise of justice, solidarity, and collective dignity.

By the mid-1960s, my father began contributing illustrations to Tariq ash-Shaab (“Path of the People”), the official newspaper of the Iraqi Communist Party, which continued to operate underground even after the Baʻath Party seized power. Despite increasing repression, he remained steadfast in his political convictions. Realizing he could no longer stay safely in Iraq, he fled the country. In 1968, he left for Yugoslavia.

As the Non-Aligned Movement gained momentum, Yugoslavia positioned itself between the Cold War blocs and fostered cultural and educational ties with post-colonial states, such as Iraq. Although Iraqi students were officially welcomed under South–South solidarity, the regime denied my father, who had no affiliation with it, any financial support. In Ljubljana, he learned Slovene, enrolled at the Academy of Fine Arts, worked by day in various factories, and spent his nights at the print studio. Although he eventually gained professional recognition, he continued to face constant pressure. He was harassed by Baʻathist-affiliated students and monitored by UDBA, the Yugoslav State Security Service. At the 1983 Biennale of Graphic Arts in Ljubljana, one of his works was nearly censored after the Iraqi embassy intervened. Officials claimed that the print contained Arabic text offensive to the Iraqi state, taking advantage of the fact that few attendees could read the language. The work was temporarily withdrawn but later reinstated after a review found the accusation to be baseless.

photo: Jaka Babnik, MGLC archive

By the 1980s, Iraq had descended into a climate of absolute fear. Political opponents were hunted, tortured, disappeared, and executed. While my father built a new life with my Slovenian mother, his residency status remained uncertain. Deportation loomed, and a return to Iraq could have meant imprisonment or worse. His brother, a member of the Communist Party, had already vanished without a trace. To this day, we still do not know what happened to him. Branded as a traitor, any contact with his relatives became too dangerous. To protect everyone, my father made the painful decision to sever ties with them entirely.

After decades of silence, I began asking questions about our Iraqi family, but my father had few answers. He had never written to them or spoken with them again. Eventually, I discovered a videotape sent by our Iraqi relatives after the fall of the regime. It was an invitation to reconnect, one that my father could not answer. Nearly two decades later, I did. That moment became the starting point for my project, The Last Sector.

I traveled to Baghdad for the first time in 2023. I discovered the material remains of the neighbourhood once known as the City of Revolution, later renamed Saddam City, and now referred to as Sadr City. The title of the project relates to a specific area within the subdivided area: the 38th sector, where my family resides. This was the outer edge of the district when my father emigrated. Although the city has since expanded, the name “The Last Sector” endures among its residents. The boundary has taken on a symbolic meaning, although its full significance remains unclear to me.

There, I met my Iraqi family for the first time. I explored the history and urban development of the area where they live and uncovered layers of family history I had never known. I documented what remained: homes made of brick and concrete, walls lined with fading photographs, and gold and green portraits of Imam Hussein that speak to their Shia tradition. I traveled south, canoed through the marshes, and observed the architecture of the arched reed houses that once defined our ancestral landscape.

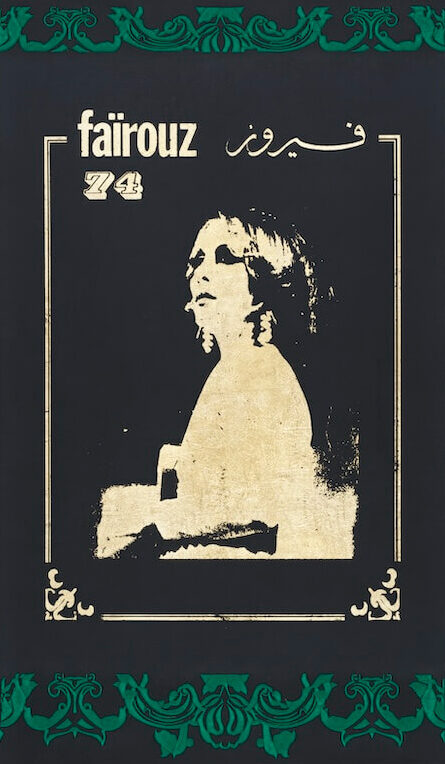

These impressions formed the visual vocabulary of the project. I translated those references into compositions using screen printing, gold leaf, digital embroidery, and laser-cut wall reliefs. The visual language drew on a wide range of motifs: Fairuz, the iconic singer whose voice shaped my father’s childhood and marked his absence, and elements from our family’s carpet patterns, which I deconstructed and reassembled, layering them with the urban grid of what was once “City of revolution.” The compositions bridge personal and collective topographies.

What began as a search for closure evolved into an exploration of the unresolved space between my father’s estrangement and my own search for identity. It connects a home remembered in fragments with one never fully known. I return, speculatively, to the City of Revolution, a landscape shaped by dislocation, failed state planning, and the endurance of those pushed to the margins. I examine how political histories leave their mark on the built environment, and how those spaces, in turn, continue to shape the lives of those who inhabit them. Though the place now bears a different name, for me it became precisely what it once claimed to be: a site of revolution, of transformation, and a threshold where an old understanding collapsed and something new, uncertain, and unfinished began to take form.

References

Batatu, Hanna. The Old Social Classes and the Revolutionary Movements of Iraq: A Study of Iraq’s Old Landed and Commercial Classes and of Its Communists, Baʻthists, and Free Officers. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1978

Gupta, Huma. Migrant Sarifa Settlements and State-Building in Iraq. PhD diss., Massachusetts Institute of Technology, 2020

Tahir, Hamid. Application for Yugoslav Citizenship and Permanent Residency

Translated documents, ca. 1980s. Unpublished family archive