[Scroll down for Farsi Version]

Mojtaba Amini explores the dual roles of artists as creators and social commentators, highlighting the tension between artistic freedom and societal pressures and the influence of political power on creative expression. His work is closely connected to his personal experiences and the violent histories of the materials he uses, which serve as metaphors for larger societal issues. Amini also critiques the ignorance and absence of serious curators in Iran’s art scene, pointing out that the dominance of galleries and commercial interests stifles true artistic expression and hinders significant artistic movements.

Davood Madadpoor: One of the concerns that have recently occupied my mind, and I would like to know your perspective on this, is the concept of being an artist. We who work and live in the Middle East, focusing on its social and political geography, might see our artistic activities take on a different hue, whether for me as a curator or you as an artist. Considering that this region is constantly undergoing social and political changes, how has your relationship with art evolved over time?

Mojtaba Amini: An artist’s beliefs and ideologies compel them to interpret and analyze political and social conditions. They then try to align these beliefs with their academic background, compare them with the realities of society, and ultimately intervene in their path forward. These alignments and contradictions can lead to growth, change, and evolution in the art and the artist’s character. Changes in society stem from the policies of power, and the citizen-artist, depending on their relationship with power, can present a form of art that constantly needs to evolve.

Pariya Ferdos[se]: Is this structural belonging a necessity? And if belonging to this structure limits the audience, can the artist find a way to overcome this limitation in presenting their work, both in the manner of presentation and in the scope of the audience?

Mojtaba: It would be better to answer this series of questions with Mikhail Bakhtin’s view on the artist, the audience, the artwork, and society. Bakhtin believes that Art is inherently and intrinsically social; when the external social environment influences art from the outside, it encounters an immediate and internal resonance within it. These two factors (art and society) are in no way alien forces that influence each other: the structure of one influences the structure of the other…Even that internal part of the artist that manifests in their work still has a social root in the artist’s subconscious, and the political or social situation of the environment provokes the artist to react in various ways. There will be no specific obligation, but there will be resistance from the artist regarding the form of presentation and the content of their works concerning environmental influences. Suppose the social conditions impact the artist as an individual in society, resulting in an artistic work and the construction of meaning. In that case, the reception of this meaning is completed in the same context where the work is created. The effort to transcend these limitations is somewhat subject to becoming fashionable.

Davood: By accepting the artist’s role, do you think we are caught up in a system that forces us to engage with it and consequently question and address it? Do you think the artist now, beyond the “traditional” role of being an artist, also assumes other roles?

Mojtaba: I think artists oscillate between the role they choose for themselves and their assigned role. Where society gives them meaning and credibility, compulsion will also be present in their work.

Davood: So, if I understand correctly, we should pause again to discuss the freedom and limitations of artists, correct? And have you, as an artist, accepted this compulsion from society? Should we call it compulsion, or perhaps a term like responsibility would better capture the sense of obligation?

Mojtaba: Artists are free, and no one has the right to tell them what to do or not do. However, when the artist, as Albert Camus says, becomes temporarily famous and derives their credibility from society and the people, they are compelled to stand with the people.

Pariya: Accepting that the artist, in your view, should stand with the people, to what extent is this possible, and if achieved, how impactful, inspirational, and effective can it be? Should the artist feel obligated to be influential?

Mojtaba: A famous artist with social capital can be influential to some extent by raising awareness and intervening in society.

Davood: Can you explain the nature and manner of these influences? Do these influences follow a particular direction?

Mojtaba: I think one of the best examples of intervention in power and the social influence of an Iranian artist is Mohammad Reza Shajarian due to his correct stance concerning the political-social events of recent years, which led to the banning of his works from state television and, more specifically, the removal of Rabbana from Iranian radio and television. His act raised many questions among the people, especially the religious part; it’s an example of the most accurate form of awareness-raising by a socially influential and well-known artist.

Pariya: Given that we have discussed the influence of political and social context and the dominant structure on the artist, how do you think, besides these factors, the intrinsic nature of the artist as a human being and their lived experience (in the form of psyche and body) impact the creation of their work?

Mojtaba: Any form of personalization in the artist’s work and the creation of art is something in continuity with others and resembles others. I mean that the creation of artistic work takes place in dialogue with others and under the influence of others in society. The “self” of the artist is not an independent existential entity; moreover, the artistic work is produced within a medium with history and past influences.

Pariya: In addition to the role and presence of the artist as a socio-political and artistic figure whose content is derived from the environment, in your work, the nature of the material and its becoming (in interaction with the environment and other materials) is evident. Where does this perspective and attention to the importance of the passage of time and the subjective nature of the material come from?

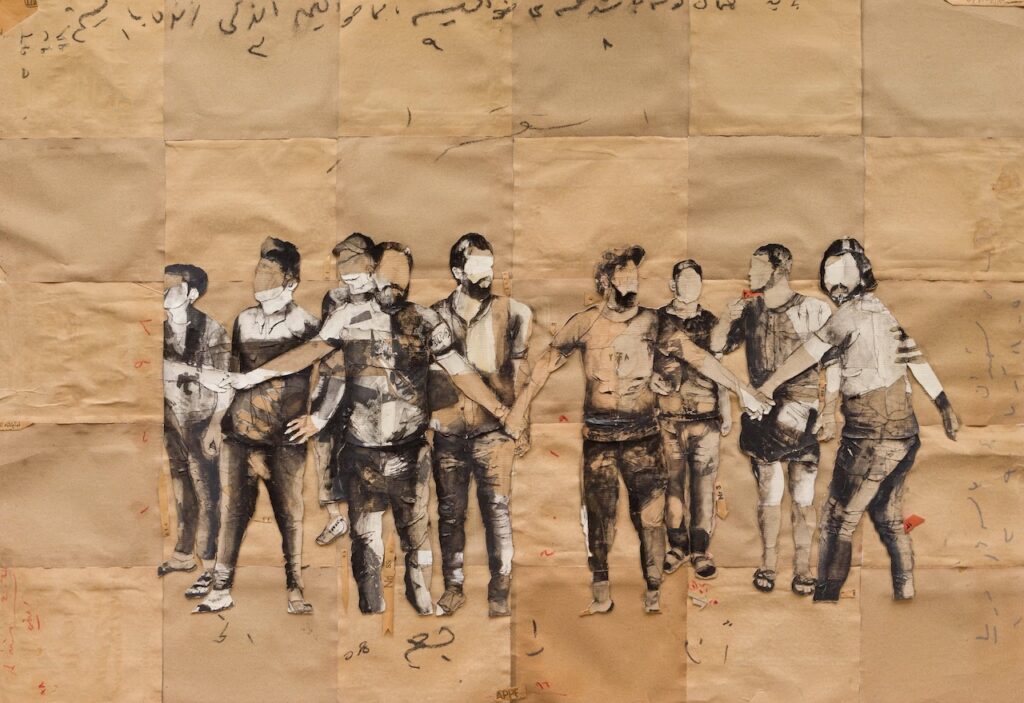

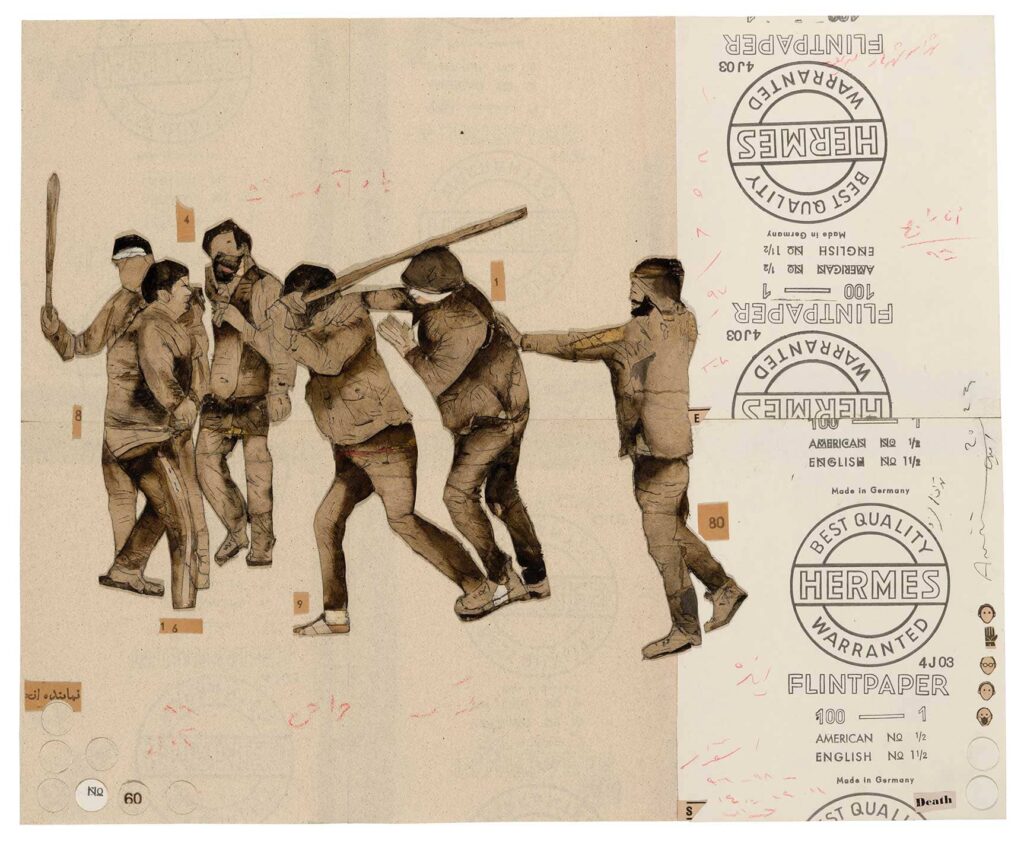

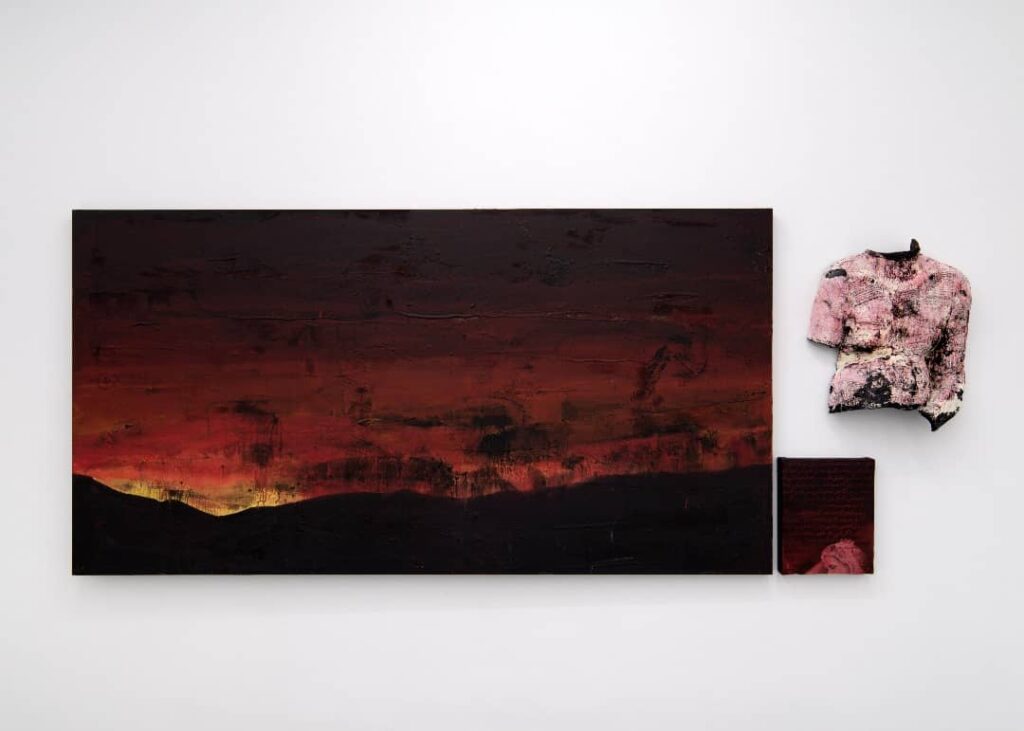

Mojtaba: I have previously answered this question elsewhere, in the book “It Transpired” Material and language have a nearly equal serious presence in my work. The material in my work has two aspects: personal and impersonal. Skin, fat, soap, and wool have a connection to my past and childhood as someone who lived in a rural farming family and witnessed the violence inflicted on animals, all of which these materials in my work are exactly “the remnants of violence” from the bodies of animals. In conjunction with the linguistic aspect of my work, which is a form of “language of violence” for me, they create that critical and socio-political meaning I intend from art. The other part of it is impersonal materials, similar to oil and tar, which are directly influenced by our political and social life, and it’s clear that no further explanation is needed here.

Pariya: And continuing, is it only the artist in this geography who should be expressive, or should other artistic roles like gallery owners, curators, dealers, etc., also be directly involved and function as an influential group or puzzle? How should this juxtaposition be?

Mojtaba: Certainly, all these elements that you mentioned are important and influential because for the three aspects of the artwork, the artist, and the audience to function correctly, the presence of all of them is necessary. However, in Iran, this coexistence does not work properly. There is no serious concept of a curator because galleries’ absolute dominance and the market’s logic do not feel the need for a curator’s presence. As a result, the artist has also lost their role and importance in this dominance. This is why we do not witness serious and specific art trends, and artists mostly produce commodities for this economic cycle.

Davood: In your opinion, what is the solution to break this flawed cycle? How can we create real convergence among artists, curators, gallery owners, and other factors to witness the formation of serious and meaningful trends?

Mojtaba: Breaking this cycle depends on the existence of independent and governmental institutions that support artists who are not inclined towards the market’s demands and tastes, as well as the existence of experimental, artist-run, and collaborative spaces.

Paria: In this process and interaction between local and global art, where do you see Iranian art in the big picture of global art?

Mojtaba: Due to the significant dispersion of the Iranian population worldwide, what is seen and presented as Iranian art is mostly within the realm of economy and market, and among this migrant population, there is nothing beyond that.

Sumac Dialogues is a place for being vocal. Here, authors and artists get together in conversations, interviews, essays and experimental forms of writing. We aim to create a space of exchange, where the published results are often the most visible manifestations of relations, friendships and collaborations built around Sumac Space. If you would like to share a collaboration proposal, please feel free to write us. We warmly invite you to follow us on Instagram and to subscribe to our newsletter and stay connected.

دشواریِ هنرمند: مولف بودن، قدرت، و مسئولیت اجتماعی

مجتبی امینی به بررسی نقش دوگانهی هنرمندان بهعنوان خالقان آثار و مفسران اجتماعی میپردازد و به تنش بین آزادی هنری و فشارهای اجتماعی و تأثیر قدرت سیاسی بر بیان خلاقانه اشاره میکند. آثار او ارتباط نزدیکی با تجربیات شخصیاش و تاریخچههای خشونتآمیز موادی دارد که از آنها استفاده میکند؛ موادی که بهعنوان استعارهای برای مسائل بزرگتر اجتماعی بهکار میروند. امینی همچنین از نادیدهگرفتن و نبود کیوریتورهای جدی در صحنه هنری ایران انتقاد میکند و بیان میکند که سلطهی گالریها و منافع تجاری، بیان واقعی هنری را سرکوب کرده و مانع از شکلگیری جنبشهای هنری مهم میشود.

داوود مددپور: یکی از دغدغههایی که اخیراً ذهن من را مشغول کرده و دوست دارم در گفتگوهایم نقطهنظر مخاطب را در این باره (دربارهاش) بدانم، مفهوم هنرمند بودن است. برای ما که در منطقه خاورمیانه، با تمرکز بر جغرافیای اجتماعی و سیاسی آن، کار و زندگی میکنیم، ممکن است فعالیتهای هنریمان رنگ و بویی دیگر به خود بگیرد؛ چه من به عنوان کیوریتور و چه شما به عنوان هنرمند. با توجه به اینکه این منطقه که دائماً دستخوش تغییرات اجتماعی و سیاسی است، رابطهی شما با هنر چگونه در طول زمان تکامل یافته است؟

مجتبی امینی: هنرمند دارای یکسری اعتقادات و باورهای فکری است که او را به تفسیر و تحلیل شرایط سیاسی و اجتماعی وامیدارد. سپس، سعی میکند این اعتقادات را با پسزمینهی مطالعاتی خود تطابق دهد، آنها را با واقعیتهای جامعه مقایسه کند و در نهایت، در مسیر پیشروی خود مداخله نماید. این تطابقات و تضادها میتوانند موجب رشد، تغییر و تکامل در هنر و شخصیت هنرمند شوند. تغییر و تحول در جامعه ناشی از سیاستهای قدرت است و شهروند–هنرمند، با توجه به نسبتی که با قدرت برقرار میکند، میتواند شکلی از هنر را ارائه دهد که به طور مداوم نیاز به تغییر داشته باشد.

پریا فردوس: آیا این تعلق بافتاری یک امر الزامی است؟ و اگر تعلق به این بافتار، جامعهی مخاطب را محدود کند، آیا هنرمند میتواند راهی پیدا کند تا این محدودیت را در ارائهی آثار خود کنار بزند؟ چه در نحوهی ارائه و چه در گسترهی جامعهی مخاطبان؟

مجتبی: شاید بهتر باشد که این مجموعه از سوالات را با نظر میخائیل باختین دربارهی هنرمند، مخاطب، کار هنری و اجتماع پاسخ دهم. باختین معتقد است: “هنر به شیوهای ذاتی و درونی، اجتماعی است؛ هنگامی که محیط اجتماعیِ برون هنری از بیرون بر هنر تاثیر میگذارد، در آن با طنینی درونی و بیدرنگ مواجه میشود. این دو عامل (هنر و اجتماع) به هیچ وجه عواملی بیگانه نیستند که بر هم تاثیر میگذارند: ساختبندی اجتماعی بر ساختبندی دیگر تاثیر میگذارد…” حتی آن بخش درونی هنرمند که در اثرش تجلی مییابد، باز هم در ناخودآگاه هنرمند ریشهی اجتماعی دارد، و وضعیت سیاسی یا اجتماعی محیط، هنرمند را به شیوههای مختلف به واکنش وا میدارد. الزام خاصی در کار نخواهد بود، اما مقاومتی از سوی هنرمند برای شکل ارائه و محتوای آثارش نسبت به تأثیرات محیط وجود خواهد داشت. اگر شرایط اجتماعی بر هنرمند بهعنوان فردی در اجتماع تأثیرگذار است و نتیجهاش اثر هنری و ساخت معناست، دریافت این معنا در همان بافتار ساخت اثر کامل میشود. تلاش برای گذر از این محدودیتها به نوعی تابع مد شدن است.

داوود: با قبول و پذیرش نقش هنرمند، آیا فکر میکنید ما درگیر شرایط و سیستمی شدهایم که ما را مجبور به ارتباط با آن و در نتیجه به پرسش کشیدن و مورد خطاب قرار دادنش میکند؟ آیا فکر میکنید که هنرمند اکنون، خارج از نقش “سنتی” هنرمند بودن، نقشهای دیگری نیز بر عهده دارد؟

مجتبی: من فکر میکنم که هنرمند بین نقشی که خودش انتخاب میکند و نقشی که به او محول میشود، در رفتوآمد است. جایی که جامعه به او معنا و اعتبار میبخشد، اجبار نیز در کارش خواهد بود.

داوود: پس اگر درست متوجه شده باشم، در اینجا باید مجددا روی آزادی و محدودیت هنرمندان مکث کنیم، درست است؟ و آیا شما به عنوان هنرمند، از سوی جامعه این اجبار را پذیرفتید؟ آیا باید اسمش را اجبار گذاشت یا شاید استفاده از واژهای مانند مسئولیت، بیشتر ادای دین کند؟

مجتبی: اساساً هنرمند آزاد است و کسی حق ندارد به او بگوید چه کند یا نکند. اما در مواقعی که هنرمند، همانطور که آلبر کامو میگوید “موقتاً مشهور” میشود و اعتبارش را از جامعه و مردم میگیرد، مجبور است که سمت مردم بایستد.

پریا: با پذیرش اینکه از نظر شما هنرمند باید سمت مردم بایستد، تا چه حد این امر امکانپذیر است و در صورت تحقق، چقدر میتواند تاثیرگذار، الهامبخش و کارآمد باشد؟ آیا هنرمند باید خود را موظف به تاثیرگذاری بداند؟

مجتبی: هنرمندی که مشهور است و سرمایه اجتماعی دارد، میتواند تا حدی با آگاهیرسانی و مداخلهگری در جامعه تاثیرگذار باشد.

داوود: میتوانید در مورد نوع و نحوه این تأثیرات برایمان توضیح دهید؟ آیا این تأثیرات سمت و سوی خاصی را دنبال میکند؟

مجتبی: به نظرم یکی از بهترین نمونههای مداخلهگری در قدرت و تأثیر اجتماعی هنرمند ایرانی، محمدرضا شجریان است. موضعگیریهای درست او در ارتباط با وقایع سیاسی-اجتماعی سالهای اخیر باعث ممنوعیت پخش آثارش از صدا و سیما، بهویژه حذف “ربنا” از این رسانه شد، که این موضوع پرسشهای زیادی را در میان مردم، بهخصوص قشر مذهبی، برانگیخت. این اتفاق نمونهای از آگاهیرسانی به شیوهای صحیح توسط هنرمندی با سرمایه اجتماعی و شناختهشده است.

پریا: با توجه به اینکه دربارهی تأثیر بافتار سیاسی و اجتماعی و ساختار غالب بر هنرمند صحبت کردیم، به نظر شما علاوه بر این عوامل، خودِ ذاتی هنرمند بهعنوان یک انسان و حیات زیستهاش (در قالب ژست روان و تن) چه تأثیری بر تولید اثر دارد؟

مجتبی: هر شکلی از شخصیسازی در کار هنرمند و تولید اثر، چیزی است در امتداد دیگری و شبیه به دیگری. منظورم این است که تولید اثر هنری چیزی است در گفتگو با دیگری و تحت تأثیر دیگری در اجتماع. “خودِ” هنرمند به عنوان یک فرد وجودی مستقل نیست و علاوه بر این، اثر هنری تولیدی است درون مدیومی که با تاریخ و تأثیرات گذشته قرار دارد.

پریا: علاوه بر نقش و حضور هنرمند به عنوان یک فیگور سیاسی-اجتماعی و هنری که محتوایش را از محیط میگیرد، در کارهای شما ذات کارماده و صیرورت آن (در تعامل با محیط و کارمادههای دیگر)، مشخص است. این نگاه و توجه به اهمیت گذر زمان و ذات سوبژکتیو کارماده از کجا میآید؟

مجتبی: پیشتر هم در کتاب “شد آنچه شد” از پروژههای ۰۰۹۸۲۱ به این پرسش دقیقاً پاسخ دادهام. در کار من، ماده و زبان هر دو به یک اندازه حضور جدی دارند. مواد بهکاررفته در آثارم تا حدی دو وجه شخصی و غیرشخصی دارند. پوست، چربی، صابون، و پشم به گذشته و کودکیام برمیگردند؛ بهعنوان فردی که در یک خانواده روستایی دامدار بزرگ شده و شاهد خشونت علیه حیوانات بوده است. این مواد که در واقع “اضافات خشونت” از بدن حیوانات هستند، در کنار بخش زبانی آثارم، که آن هم بهنوعی برایم “زبان خشونت” است، معنای مورد نظر من از هنر را به شکل انتقادی و سیاسی-اجتماعی میسازند. بخش دیگر مواد غیرشخصیاند، مانند نفت و قیر، که مستقیماً از زیست سیاسی و اجتماعی ما تأثیر میگیرند و نیازی به توضیح بیشتر ندارند.

پریا: و در ادامه، آیا تنها هنرمند است که در این جغرافیا باید بیانگر باشد، یا باقی سمتهای هنری مانند گالریدار، کیوریتور، دیلر و… هم باید به صورت مستقیم و بهعنوان یک گروه یا پازل تاثیرگذار باشند؟ بهنظرتان این کنارهمقرارگیری (juxtaposition) چگونه باید باشد؟

مجتبی: قطعاً همه این عناصر که شما نام بردید اهمیت دارند و تاثیرگذارند، زیرا برای اینکه سه وجه اثر هنری، هنرمند و مخاطب بهدرستی عمل کنند، حضور همهی آنها لازم است. اما به نظرم این کنار هم بودنها در ایران درست کار نمیکند. کیوریتور به معنای جدی وجود ندارد، زیرا سلطه بیچونوچرای گالریها و منطق بازار نیازی به حضور کیوریتور احساس نمیکند و در نتیجه، هنرمند نیز نقش و اهمیت خود را در این سلطه از دست داده است. به همین دلیل است که جریان جدی و خاصی در هنر را شاهد نیستیم و هنرمندان بیشتر در حال تولید کالاهایی برای این چرخه اقتصادی هستند.

داوود: به نظر شما راهکار شکست این چرخه نادرست چیست؟ چگونه میتوان همگرایی واقعی میان هنرمند، کیوریتور، گالریدار و سایر عوامل را ایجاد کرد تا شاهد شکلگیری جریانهای جدی و معنادار باشیم؟

مجتبی: شکستن این چرخه نیازمند وجود نهادهای مستقل و دولتی است که از هنرمندانی حمایت کنند که تمایلی به تبعیت از خواست و سلیقه بازار ندارند. همچنین، ایجاد فضاهای تجربی، هنرمندگردان، و اشتراکی نیز ضروری است.

پریا: در این روند و تعامل میان هنر محلی و جهانی، هنر ایران را در کجای مختصات تصویر بزرگ هنر جهانی (big picture) میبینید؟

مجتبی: به دلیل پراکندگی بخش قابلتوجهی از جمعیت ایران در جهان، آنچه از هنر ایران دیده و ارائه میشود، بیشتر در حیطه اقتصاد و بازار قرار دارد و در میان این جمعیت مهاجر، چیزی بیش از این نیست.