Sumac Dialogues is a place for being vocal. Here, authors and artists come together in conversations, interviews, essays, and experimental forms of writing. It is a textual space to navigate the art practices of West Asia and its diasporas which emphasize critical thinking in art. If you have a collaboration proposal or an idea for contribution, we’d be happy to discuss it. Meanwhile, subscribe to our newsletter and be part of a connected network.

exhibition Acts of Conflactions, Galerie AC. Art & Dialogue, Berlin 2025, courtesy of Sumac Space

There is no outside-text.

The trace is not a presence but the simulacrum of a presence that dislocates, displaces, and refers beyond itself.¹

_Jacques Derrida

Field of Vision… Field of Narrative

Yasmin Nourbakhsh’s works are not isolated objects but situational configurations: each generates a situation—a perception, a memory, a narrative. These are layered and liminal, occupying a space neither fully here nor there—mirroring where the artist lives: between Iran and the UK, between languages and memories; never entirely in one place.

Yasmin Nourbakhsh’s work explores politics on a microscale, revealing it in the empty space where a pattern might have continued or in a colored shadow falling from glass. Rather than emphasizing slogans or grand icons, Nourbakhsh shifts our field of attention. In her art, politics is about how attention is regulated: she displaces the center and margin, alters intensity, and plays with light and dark.

Trace, Erasure, Palimpsest

Derrida uses the term trace for that subtle sign of absence that simultaneously enables meaning and its indeterminacy. Derrida’s trace signals both presence and absence; it always points beyond itself, remains unstable, and keeps meaning alive through continual interaction with other signs. In Nourbakhsh’s works, traces appear as thin layers of erased paint or partially covered images. Rather than stabilizing form, she suspends it; rather than making narrative uniform, she emphasizes ruptures. The work becomes a palimpsest: earlier writings emerge beneath the new—erased yet present, spectral.

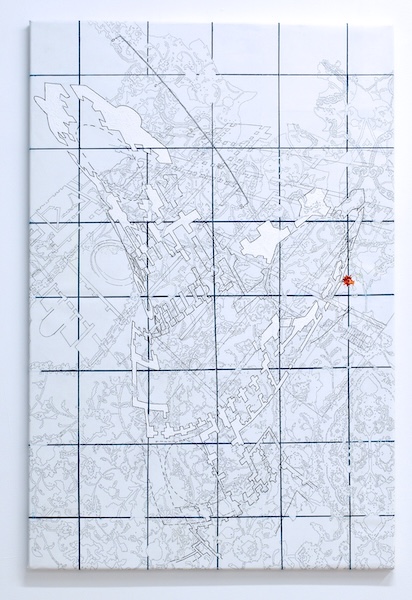

Walter Benjamin, when writing about “the true image of the past that flees in fragments and signs,” articulates precisely this logic: history is neither linear nor continuous; it shines in the flashes of moments, in fragments and seemingly insignificant grooves. Nourbakhsh frames these small sparks by shifting minor elements—a piece of vintage glass, an incomplete pattern, a faded floor plan, or a sliced map—inviting the viewer to listen to the fragment rather than merely observe the whole; a fragment that carries history.

Erasure in Nourbakhsh´s practice is not merely a formalistic gesture; it is not merely folding a surface for beauty, but rather revealing the politics of concealment. Erasure in her work is both an aesthetic and epistemic strategy: by removing parts of a pattern, covering sections of an image, she raises the question: What is seen? What is erased? Who decides? These questions mark the point where the critique of representation begins.

80×120 cm, Acrylic pen, oil stick and image transfer on canvas

Selective Perception

Every perception is selective. We see the world through filters we conceal: visual habits, media, collective memory, cultural biases. Nourbakhsh makes this selectivity the subject of her work. The repetition of motifs and modular grid form, when deliberately broken or incomplete, draws attention to the act of choice itself: a pattern can continue but is interrupted; why and how? A background sound may rise but remain on the threshold of audibility; for what reason? These threshold zones are the liminality of perception: boundaries where seeing/not seeing occur simultaneously, forcing the viewer to recalibrate their position.

This selective perception in Nourbakhsh’s work extends beyond the material itself; it also carries the memory of the material—what touches a fabric recalls, what scratches a glass retains, and the paths colored threads have followed—each element becoming part of the work’s logic. Nourbakhsh works with tactile sensitivity: slow, precise, with deliberate pauses and thoughtful returns. In her work, memory and material engage in a dynamic dialogue; as a living archive, memory transforms from outcome to process, from action to being.

Nourbakhsh brings this duality to the surface: the beauty of a pattern beside the wound of erasure; symmetrical repetition alongside a gap of removal. In this sense, her works become a space where beauty and wound coexist, where the viewer moves from formal fascination to a deeper political inquiry.

In-betweenness and liminality

Nourbakhsh lives in a diasporic condition. This in-betweenness is not just geographical; it shapes the work’s being. Her work and life are dual and multilayered: languages overlap, translations slip, signs shift—Persian/English, text/sound, image/word. Translation is not a solution for understanding; form becomes difference. Where pattern is complete, a gap appears; where narrative takes shape, silence arises; where material seems familiar, something foreign emerges.

Meanwhile, the presence of the Others from East in West—a subject discussed by Edward Said—is actively staged in Nourbakhsh’s work. Said argued that the Eastern Other (here: the West Asian Other)

In Western representational history, it is always constructed under the influence of power. Nourbakhsh reverses this logic: rather than aligning signs to confirm cultural expectations, she displaces and disrupts them. Familiar patterns are left incomplete, pleasant colors are juxtaposed with material silence, and nostalgic narratives are interrupted by signs of anxiety.

Her work disrupts the game of representation: instead of the East appearing as a consumable image in cultural vitrives, the vitrives themselves become sites of inquiry. Patterns, geometric motifs, and bright colors, stained glass: rather than fixed markers of authenticity, they become tools of critique. Here, the artist is not an exoticized subject but an agent of meaning; someone who disrupts the rules of seeing and shifts the position of the dominant gaze.

Nourbakhsh’s works create liminal spaces: thresholds between presence/absence, seeing/not seeing, speaking/silence. These manifest in the material (semi-transparent glass, worn fabric, unstable paint), form (incomplete patterns, disrupted geometry, broken frames), and meaning (narratives that begin but continue through the viewer). The audience becomes a co-author, filling gaps and generating meaning through their engagement.

Liminality shapes the ethics of engagement: Nourbakhsh’s work stands between formal pleasure and political provocation, keeping viewers at the threshold. This is also a curatorial gesture: the display creates a rhythm of near/far, light/dark, sound and silence/silence so that being on the threshold is experienced.

Thinking Material

Material memory is a term describing Nourbakhsh’s relationship with material and effective image transfer. The painting surface, ineffective Quartz, masked edges, dust, and paint stains all carry time. Material is not merely something to work with; it is a deposit of time. Nourbakhsh treats material not as a servant of ideas but as a co-thinker. Hence, the acts of touching, washing, masking, collaging, cutting, removing, and placing all become conceptual gestures.

This organic quality of pattern is evident: patterns grow, are cut, regrow; like plants, like skin, like memory. When a pattern is erased, its trace remains; when removed, its absence becomes active; when repeated, meaning transforms. This repetition/erasure simultaneously tests the semiotic system and our perceptual system.

Two Metaphors of Life-Space

The Iranian Garden and carpet in Nourbakhsh’s works serve as spatial metaphors that weave the themes of memory, refuge, and order. The carpet is the portable ground of the home; a soft geography on which we sit, sleep, and narrate. The carpet is a site of memory: fibers record footsteps; knots count moments. In Benjaminian reading, the carpet is “a miniature stage of history”: fragmented, layered, with margins and gaps. Nourbakhsh removes this scene from mere decoration, turning it into a site of inquiry: which narratives are fixed on the carpet’s surface and which are lost in its pile?

The Iranian Garden, with its fourfold layout, waterways, light, and shadow, is reread in Nourbakhsh’s work as a site of control and uncertainty. The garden embodies a desire for heavenly order amidst worldly disorder; yet nature always overflows: a branch outside the line, a root breaking stone, water seeking its own course. Nourbakhsh exploits this duality: geometric patterns of the garden sit alongside organic growth patterns, showing that every order speaks with the life of disorder within itself.

From Trace to Recognition

Yasmin Nourbakhsh’s works employ strategies that ultimately lead to recognition: the recognition of memory traces in material, the recognition of erasure as a tool of seeing, and the recognition of the Other as the viewer. This recognition is not a nostalgic return to origins, but an invitation to live with gaps: gaps in languages, geographies, and narratives.

Nourbakhsh, as artist/researcher, demonstrates how beauty can be apprehended—without overlooking politics—and how politics can be enacted—without sacrificing formal subtlety. Through the economy of layering and erasure, the rhythm of repetition and rupture, and her sensitivity to material and time, she creates an experience where the audience not only sees but also thinks, hears, touches, and remembers.

What remains is “art as a living archive”: an archive that asks what is seen and why, what is erased and how, what remains and at what cost. And also “art as threshold”: a place to stand, pause, pass; a site where new possibilities of perception and dialogue are opened.

Nourbakhsh reminds us that memory is never fully present, yet its trace remains in material; repetition is never flawless, yet erasure aids seeing; the Other is never merely an object but can be a subject of the gaze; and text is never alone, always breathing in a network of other texts. It is in this networked breath that her works grow: organic, resilient, continuously reweaving themselves; like a garden whose geometry is meticulously arranged yet surprises with new growth each morning.

Pariya Ferdos[se]

Tehran, Semptember 2025

References

- 1Derrida, Jacques. Writing and Difference, Translated by Ahmad Aram, Tehran: Nashr-e Ney, p. 45.

- Benjamin, Walter. Illuminations: Essays and Reflections. Edited by Hannah Arendt. Translated by Harry Zohn. New York: Schocken Books, 1968.

- Said, Edward. Orientalism. Trans. Dr. Abdolrahim Gavaahi, Tehran: Nashr-e Farhang-e Eslami.

- McAfee, Noel. Julia Kristeva. Trans. Mehrdad Parsa, Tehran: Nashr-e Markaz.

- Benjamin, Walter. The Author as Producer. Translated by Iman Ganji and Keyvan Mahtadi, Tehran: Nashr-e Zavosh.

- Adorno, Theodor, Judith Butler, and Georg Lukács. The Politics of Essays. Translated by Saleh Najafi, Morad Farhadpour, Reza Rezaei, and Amir Kamali, Tehran: Nashr-e Ney.

- Benjamin, Walter. On Language and History. Selection and Translated byMorad Farhadpour and Omid Mehregan, Tehran: Nashr-e Hermes.

- Noorbakhsh, Yasmin. Who Is It That Can Say Who I Am?: Reconfiguring Art in a Liminal Space. Critical Model dissertation