Sumac Dialogues is a place for being vocal. Here, authors and artists come together in conversations, interviews, essays, and experimental forms of writing. It is a textual space to navigate the art practices of West Asia and its diasporas which emphasize critical thinking in art. If you have a collaboration proposal or an idea for contribution, we’d be happy to discuss it. Meanwhile, subscribe to our newsletter and be part of a connected network.

İpek Çınar: At first glance, our practices and outcomes may appear quite different, but I sense they stem from similar concerns and struggles. That makes me especially curious about this exchange. So let me start directly: How would you describe what you do at the intersection of art, participation, and politics?

Reyhaneh Mirjahani: I would describe my art practice primarily as a mode of critical investigation. Rather than positioning art as an end in itself, I approach it as a methodological and epistemological tool—one that enables me to examine and intervene in a socio-political situation, an issue, or a tension. Ideally, it serves as a mode of inquiry capable of activating forms of knowledge production that are embodied, situated, and relational.

I rarely begin with art as such. I tend to start with a question or conflict, using art to probe, study, re-read, and reframe a situation. I am especially curious about the entanglements between power, counter-narratives, ethics, and lived experience. I focus on how these forces shape one another and structure the conditions for participation, responsibility, or agency. Initially, my interest was grounded in theoretical frameworks. Over time, I have become more drawn to the capacity of artistic practice to generate alternative research modes. These modes resist abstraction and instead foreground affect, contingency, and embodied experience.

I try to approach art not only as a representation, but as a speculative and experimental space. Here, dominant logics can be discussed, redefined, or reimagined. Art enables the exploration of new ways of relating, the rehearsal of ethical positions, and the co-creation of shared meaning. I am interested in how these spaces can offer conditions for critical reflection that go beyond cognition. They are also embodied and effective. This brings the possibility of more nuanced and plural understandings of participation, responsibility, and the political.

İpek: Your earlier works address identity and belonging through guest/host and self/other tensions, but later take on a more transnational, relational focus. Looking back, what questions or dilemmas prompted this shift in direction for you? Was it a gradual evolution or a response to particular challenges?

Reyhaneh: We grow up in systems that are keen to define our lived experiences through dichotomies. It is a way to simplify situations, and we are taught to think in the same terms. Over the years, I have shifted my attention toward what lies between these categories. I want to grasp the complexity of relationships and to resist static interpretations of events.

This has transformed my practice. My work is no longer primarily about my own identity or position. Instead, I focus on how, as subjects, we navigate the contexts and systems in which we live. Dialogue and participation become essential. They create opportunities to explore and understand the diverse, dynamic experiences of others. At the same time, they help reveal the politics that shape participation and dialogue.

İpek: From what you’ve described, art for you seems to exist as both something projected into the future (the not yet) and as a process that unfolds. In your participatory works, many elements are involved: planning, realization, documentation, participant input, unexpected encounters, and the tensions of the moment. All of these meet in a speculative space. With so many variables, how do you see your role in this process? For example, how do you position yourself in the room?

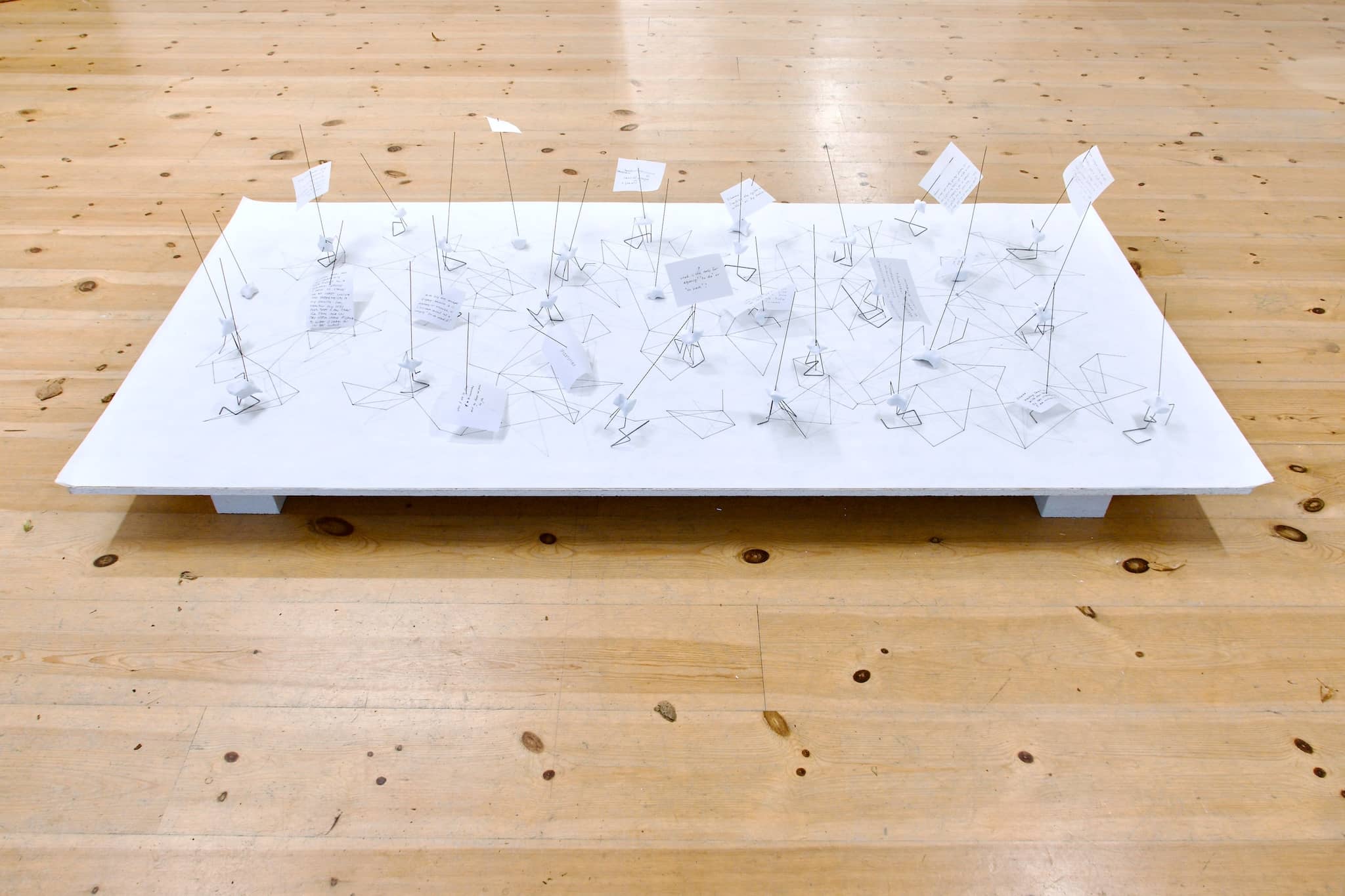

Reyhaneh: I would describe my role in participatory projects as a facilitator. During the preparation and development phases, I established a framework with specific elements and cues. These questions or concerns are what I want to explore with participants. These elements act as subtle guideposts, not strict instructions.

Once the work begins, I try to step back and leave space for participants to interpret and respond on their own terms. I consider this openness essential. It allows the unexpected to emerge in both content and group dynamics. Sometimes I intervene during the activation phase, usually by asking a question or subtly shifting the group’s attention. My aim is to stay responsive rather than directive. I try to inhabit a space between author and participant. This lets me guide without closing possibilities, and to unfold relationally, shaped by the moment—whether social, political, or interpersonal.

But this brings me to a key question about your own practice: How do you define your role within the Orta Okul project that you initiate? In your view, how does your positioning affect dynamics, openness, and the potential for unexpected outcomes?

İpek: Initiate is the correct word. I usually describe myself not as an artist, but as an initiator. Even this role can influence a project’s dynamics more than I expect or want to admit. My solution is to carefully specify which groups I work with and spend more time with them. I dedicate time to understanding the community’s dynamics and learning about them. Whenever possible, I exchange ideas with them before the project begins. This helps my vision align with the community’s reality and wishes.

This approach involves compromises. Instead of working in galleries, museums, or staging public interventions, I often work in spaces where the community feels safer. Sometimes, I commit to longer-term collaborations. For example, in a recent project with Orta Okul, we spent several months meeting with the community every Friday. Sometimes, we did nothing more than ask, How do you perceive what we are doing together? Ultimately, we did not produce exactly what we had planned. But the process taught us about participation, empowerment, and building connections. Some women began referring to it as our project rather than your project. A few even wanted to take the initiative to continue it independently. This was an unexpected, yet deeply valuable, outcome.

I would like to specifically focus on your upcoming work, An Experiment on Agency #8, which will be part of Acts of Conflations and is the reason we met. This project continues a series that has already engaged diverse geographies, including Latvia, the Netherlands, Italy, and Sweden. Could you discuss the overall framework of this work and how you have adapted it to various contexts?

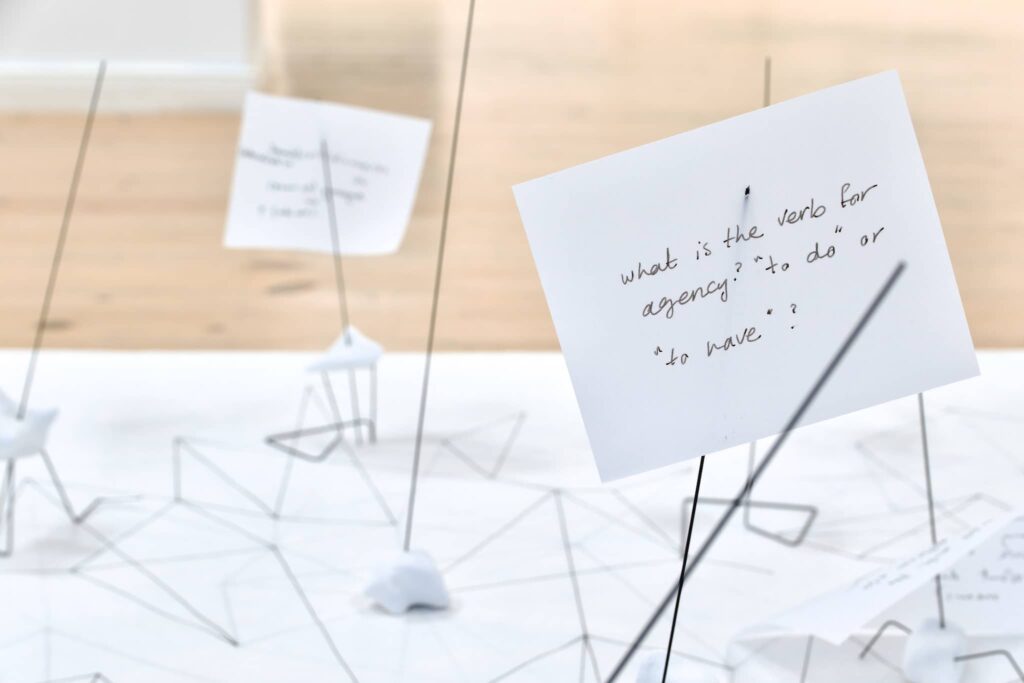

Reyhaneh: This work is designed to create a space where friction, disagreement, and discussion are not only possible but necessary. I have noticed that conversations around agency often get trapped in rigid dichotomies: either one has agency or one does not. In An Experiment on Agency, I seek to disrupt these binaries by foregrounding contexts in which agency is ambiguous, unstable, or constantly shifting. The work invites participants to explore subjective understandings of power and responsibility, rooted in lived experience rather than abstract definitions.

While I actively shape each version of the work based on its context, the project itself also evolves. The context not only informs the realization of the work, but also transforms it. Each iteration responds to dilemmas specific to the setting. These may relate to geography, sociopolitical conditions, or the group’s composition. During the activation phase, participants further shape the work, often steering discussions toward their own concerns and group dynamics. For example, in Riga, one participant group consisted of humanities secondary school teachers. In the Netherlands, it was a group of artists and researchers in socially oriented and academic practices. Each setting brought new questions: What kind of language emerges around the concept of agency? How do we discuss responsibility in a group of nations in conflict? What does it mean to claim neutrality? What happens when the agency shows up as refusal, withdrawal, or silence rather than action? And how do aesthetics operate in this participatory format?

İpek: Sharing agency is as challenging and risky as political, often feeling like the subject investigates you as much as you investigate it. Why is it so central to the series?

Reyhaneh: At first, I approached the agency as something granted, and I was interested in how we could exercise it. Later, during research phases, I began to question that premise entirely. Some scholars argue that agency can be imposed, involuntary, or even illusory. This was a turning point for me—not only for the project, but also for my own understanding of the concept. From there, the focus shifted toward examining different forms of agency and the structures that either limit or enable it, as well as the dilemmas and liminal spaces in between that we need to navigate.

I personally had the privilege of growing up around some activists and civic actors in my hometown of Tehran. That environment initiated many questions about our agency, responsibility, and ethics, situated between an authoritarian regime and imperial powers. For me, these questions are inseparable from my lived experience, regardless of where I am or the privileges I hold. I believe that engaging with this subject reveals much about our own subjective positions, standing in contrast to purely empirical research on the topic and challenging the binary frameworks through which the world is so often understood.

İpek: And what will you be exploring specifically in the Berlin context?

Reyhaneh: In Berlin, I am particularly interested in continuing this investigation at a time when violence is intensifying. Specifically, in the context of the ongoing genocidal acts and the immense human suffering of the civilian population in Gaza, the response we’ve seen in Germany—mirroring similar trends in some other Western countries—reveals a growing repression of protest and political movements. Within this climate, a central question emerges: how can we hold space for conflict without collapsing into consensus? And how can we meaningfully engage with the notion of agency when speaking out becomes a risk, and visibility itself can be weaponized?

I am not sure that it will open up new ways in a radical sense, but it will emphasize the already existing resources in our society: the capacity to share and to listen. I do not mean this passively; rather, it is a deliberate engagement with doubt, dilemmas, and insecurity, creating a space where these tensions can be acknowledged and discussed. The aim is not necessarily to provide answers, but to trace and understand the different structures at play in shaping experience and agency. This is what I hope to realize in the exhibition.

At the same time, I also want to acknowledge my own doubts. To what extent can conversation alone generate alternative approaches to entrenched situations? How much space can we truly give to antagonism in a context where we are still confronting the very real legacies of oppression and violence? Under what conditions, and when, are we allowed to engage in agonism, and when must we prioritize care, listening, or safety?

I’m curious about your perspective on working in Berlin today. How do the specific conditions, tensions, and opportunities here shape the way you think about agency in your own projects? And how does this affect your work with Orta Okul or similar participatory initiatives?

İpek: What you say is extremely important and a pressing issue in Germany, one that we all face in different ways. We are confronted both with the complicity of the country we live in regarding genocide and with the hypocrisy of institutions that have benefited from post-migrant, anti-colonial, and feminist discourse, which remain silent and try to silence us. Yet we remain here, because there is no other place to go.

At Orta Okul, we have dedicated our first three years to topics related to this: Urgency (2024), Community (2025), and Resilience (2026). Our aim is to strengthen collective bonds and allocate the limited resources we or our fellows have. I find both ease and political engagement in empowering individuals, using the methods you mentioned: care, listening, and creating safer spaces, especially for those in more difficult positions. It may sound simple, but after seeing how institutions complicate these topics, I believe we need a bit of simplicity and directness. And more spaces to discuss. Perhaps for this reason, we need An Experiment on Agency now more than ever.

Reyhaneh Mirjahani is an artist working at the intersection of visual art, curating, artistic research, organizing, and publishing, focusing on participatory art. She uses collaborative, interdisciplinary approaches to create dialogic spaces exploring agency, participation, counter-narratives, and spatial politics. She holds an MFA in Fine Art from HDK-Valand, Gothenburg University, and has completed the postmaster programs Commissioning and Curating Contemporary Public Art at HDK-Valand and CuratorLab at Konstfack.

Ipek Çınar is an artist and researcher working predominantly with participatory and socially engaged art practices. She uses play, joy, and unexpected encounters as means of expression. She studied Political Science at METU Ankara and Art in Context at UdK Berlin, and is currently a PhD candidate at the Academy of Fine Arts Vienna. Alongside her artistic production, she also works in the field of anti-discrimination and social justice. İpek Çınar loves the word “Orta” (Middle): She is co-editor of Orta Format and is a co-founder of Orta Okul.