[Scroll down for Farsi Version]

Mitra Soltani shares how her experiences with instability, lack of agency, and being a woman have shaped her projects. The conversation explores the evolving roles of the artist, the unique imprints they leave, and the intersection of gender, embodiment, gesture, and indigenous context in her work. The conversation not only addresses the duties and limitations of artists in society but also emphasizes the crucial role of the artist in shaping societal narratives, the power of juxtaposition, and the role of art professionals in bridging the local and global art scenes.

Davood Madadpoor: I want to start the conversation with a general question about being an artist. The concept of being an artist differs in local and international contexts. Coming from the Middle East (with a focus on its social and political geography), we may add a different flavor to the concept of being an artist through our artistic activities. Considering living in a region constantly undergoing social and political changes, how has your relationship with art evolved?

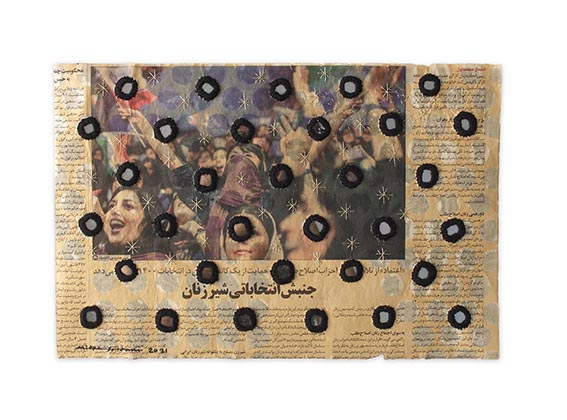

Mitra Soltani: In recent projects like Showing Transparency and A Number of Monuments, my direct experience with the subject has been central to my work. The daily experience of insecurity and lack of any form of stability is a state that deprives the human/artist of any sense of “agency.” For me, art’s function is a way to fight or resist the feeling of being objectified in such a situation. My work involves collecting archives, working with low-value or ephemeral materials, and exploring the lifestyle and art of local tribes and nomads.

Davood: Mitra, you made an interesting point! How can we reconcile the contradiction between the lack of agency for the artist and using artistic methods as a form of struggle?

Mitra: The example is local women’s way of life and art, inspiring this project. These women live in challenging conditions with countless restrictions imposed by society, family, and nature. However, all these limitations do not result in them being passive; instead, they impact their surroundings by employing art and rituals bit by bit. This impact deepens and spreads to the point where it even infiltrates their society’s most challenging and male-dominated structures. For me, defining agency is something like this.

Davood: By accepting the artist’s role, do you think we are engaged in a particular situation and system that compels us to interact with it, thus questioning and addressing it? Do you think the artist now has other roles beyond the “traditional” role of being an artist?

Mitra: I find this question challenging. I don’t fully understand the concept of an artist’s “traditional” role. Perhaps it means that the role of art in its traditional form was static and has changed over time. However, I’m afraid I have to disagree with this idea. Every example that comes to mind, whether historical or traditional, shows the artist constantly asking questions, challenging assumptions, and transforming. Therefore, the artist has not assumed a new role; what has changed is the way of thinking and expression, which has evolved with the times.

Regarding the first part of the question, since I consider freedom the most essential characteristic of art, I don’t think the artist is “compelled” in any field. However, I feel trapped in a system and am trying to find a way out.

Pariya Ferdosse: Given that you mentioned being trapped in a system, I will rephrase Davood’s first question differently: is this contextual attachment a necessity? And if this attachment to the context limits the audience, can the artist overcome this limitation in presenting their works? (Both in presentation and the audience)

Mitra: For me, the work was created within the context of my living environment, making it impossible to think or develop detachedly. Essentially, this compulsion and a sense of helplessness shaped the idea of the work. Regarding the audience limitation, it is natural for each work to have its audience. I have created many projects in nature, Indigenous environments, and public and urban spaces that have attracted a wide range of audiences, and works like this project probably have a more limited audience. In other words, I am not particularly insistent that all my works have the same or a broad audience.

Pariya: In this context, how does the intrinsic nature of the artist as a human being and their lived experience (in the form of a posture – both mental and physical) impact the production of the work, considering that some of your works remind me of Hannah Wilke and particularly Ana Mendieta? (I ask this question in line with your discussion about the lifestyle of nomadic women and how gender and embodiment have entered your methodology and working style.)

Mitra: It is hard to imagine an artist who can think about art or create something detached from their lived experience. The only question is how tangible this impact is. Essentially, this work and most of my projects are based on my lived experience in a native and ritualistic culture, both in subject matter and working method. I am inclined toward a form of conceptual art that relates to ritualistic actions, literature and nature are other essential components of my artistic practice. All these elements directly arise from the life of my mind and body in such a context. A specific example is works entirely based on ritualistic behaviour, and ritual cannot be understood from the outside. This topic underscores the importance of the body and gender in my works, as the relationship between body and gender and their dialogue with nature gives rise to rituals.

Davood: What differentiates an artist who feels responsible towards society from groups like politicians or social scientists who seek to imagine and create a new future?

Mitra: It is more logical to think about the similarities rather than the differences because this distinction is fundamental. An artist uses their freedom, sensitivity, and creativity. They can internalize issues and present intangible aspects. They move independently of the boundaries and limits of any discipline and thus deal not with explaining issues but with perceiving disasters or ideal situations. For example, my experience with some artworks with socio-political concerns (amid the constant flow of world news and information, which quickly trivializes every important matter) has been like a pause or break. This pause suggests different ways of seeing and thinking and keeps the hope for change alive through creativity.

Pariya: Assuming that you believe the artist should stand by the people, how feasible is this, and if achieved, how impactful, inspiring, and functional is it? Should the artists consider themselves obligated to be impactful?

Mitra: I believe the artist should not necessarily stand by the people, and I can’t define a “should” for the artist. I only know that art is closer to freedom than anything else, or at least it should be. Therefore, in a dictatorial society, the side of freedom is likely the opposite of power in most cases.

Regarding obligation, as I said, I cannot impose a duty on the artist; I think more about the commitment to art itself. I am still determining its functionality, which significantly depends on the social conditions in which we are active. Still, regarding inspiration, I agree that artistic endeavor is fundamentally inspiring, and we can think about its quantity and quality.

Pariya: In this context, is it only the artist who should be expressive, or do other artistic roles like gallery owners, curators, dealers, etc., also have a direct impact and function as a group or puzzle? How do you see this juxtaposition?

Mitra: Any form of expression or impact in art results from a set of choices. Naturally, in these choices, other players in the art field, such as gallery owners, curators, dealers, critics, etc., play an important role. As we have often seen, artists with prominent discourses have been marginalized while less significant productions have been highlighted. In the case of my projects, this juxtaposition has usually not been very successful because in such projects, the roles of others, including gallery owners, curators, etc., are more significant in presenting the work, and many challenges make them less inclined towards such projects.

Pariya: In this process and the interaction between local and global art, where do you see modern (contemporary) Iranian art in the big picture of global art?

Mitra: I am not very optimistic about works that have a closer connection to indigenous contexts. I only know a few successful examples of such art. By success, I mean being recognized in the global picture, as you mentioned. Because I think the global/Western view of other societies is still negligent and colonial in that they always pay attention to easily accessible and exotic images and ideas, not those that require a deeper understanding.

Mitra Soltani is an interdisciplinary artist interested in the relationship between literature, culture, and everyday life. She always uses objects that reflect the history and identity of the culture. Her work seeks new experiences of dealing with material and concept by exploring indigenous art practices and literature. She received a bachelor’s degree in painting from Shahed University of Tehran and a master’s degree in graphics from Tehran University of Art. Soltani has participated in more than thirty group exhibitions and art festivals and biennials and has made a number of projects in urban spaces and nature. Instagram

Pariya Fedros[se] is a curator, researcher, writer, and architect working on intersectional curatorial methodology and practices based on comparative methods, discourses, and texts. She started her career in art as an art director at age 26. After being cofounder and art director of two galleries, and because of her background in studying computer science, architecture, and philosophy (especially Eastern), she decided to extend her experiences to interdisciplinary research/text–oriented curating and architectural projects. She curated and designed Tehran’s Trilogy in three different exhibitions in Tehran’s central and ancient neighborhood (2017-2018). She was a researcher in the project exhibited in CAAM [Contemporary Art Museum in the Canary Islands]. Named Human All Too Human based on the ideas of the Iranian philosopher Suhrawardi (2018-2021). She curated an exhibition called Melencolia I with nine artists from four countries following comparative methodology and bridging art history inspiration, cinema, and psychology; this project took nine months (2022-2023). She was one of the writers in the book Rethinking the Contemporary Art of Iran by Hamid Keshmirshekan (2023). Recently, she’s been working on curational and publishing projects on different topics, such as Iranian literature, mysticism and immigration.

Sumac Dialogues is a place for being vocal. Here, authors and artists get together in conversations, interviews, essays and experimental forms of writing. We aim to create a space of exchange, where the published results are often the most visible manifestations of relations, friendships and collaborations built around Sumac Space. If you would like to share a collaboration proposal, please feel free to write us. We warmly invite you to follow us on Instagram and to subscribe to our newsletter and stay connected.

عاملیت، فعل (یا رویههای) روزمره به مثابه مقامتی در برابر حذف شدن

میترا سلطانی چگونگی شکلگیری پروژههایش براساس تجربیات خود از بیثباتی، فقدان عاملیت و زن بودن را به اشتراک می گذارد. این گفتگو به بررسی نقشهای رو به تکامل هنرمند، اثر منحصر به فردی که از خود به جا میگذارند، و تلاقی جنسیت، بدنمندی، ژست و بافتار بومی در آثار او میپردازد. این گفتگو نه تنها به وظایف و محدودیتهای هنرمندان در جامعه میپردازد، بلکه بر نقش حیاتی هنرمند در شکلدهی روایتهای اجتماعی، قدرت همنشینی و نقش متخصصان هنر در پل زدن میان عرصههای هنری محلی و جهانی تأکید میکند.

داوود مددپور: میخواهم گفتگو را با یک سوال کلی درباره مفهوم هنرمند بودن آغاز کنم. من معتقدم که مفهوم هنرمند بودن در دو بافتار مختلف؛ محلی و بینالمللی، متفاوت است. ما که از خاورمیانه (با تمرکز بر جغرافیای اجتماعی و سیاسی آن) میآییم، ممکن است با فعالیتهای هنریمان رنگ و بویی دیگر به مفهوم هنرمند بدهیم. با توجه به زندگی در این منطقه که دستخوش تغییرات اجتماعی و سیاسی مداوم است، چگونه رابطهی شما با هنر در طول زمان تکامل یافته است؟

میترا سلطانی: در پروژههای اخیرم مانند Showing Transparency و A Number of Monuments، تجربهی مستقیم از موضوع کارم بوده است. تجربهی روزمرهی ناامنی و فقدان هر شکلی از ثبات، وضعیتی است که انسان/هنرمند را از احساس هر گونه “عاملیت” خالی میکند. در حال حاضر، کارکرد هنر برای من راهی برای مبارزه یا مقاومت در برابر احساس شیء شدگی در چنین وضعیتیست که این راه شامل جمعآوری آرشیوها، کار با متریال کمارزش یا کمدوام و همچنین جستجو در شیوهی زندگی و هنر اقوام و عشایر میشود.

داوود: میترا نکتهی جالبی را مطرح کردی! به نظرت چگونه میتوان این تناقض بین تهی بودن از عاملیت هنرمند و بهرهگیری از شیوهی هنری به عنوان راهی برای مبارزه، را کنار هم قرار داد؟

میترا: مثالش همان شیوهای است که در شکل زندگی و هنر زنان محلی میبینم که در این پروژه نیز الهام بخش من بوده است. این زنان بیشتر در شرایطی بسیار دشوار و با محدودیتهای بیشماری از سوی جامعه، خانواده و طبیعت زندگی میکنند. اما همهی این محدودیتها باعث نمیشود که آنها از عملکرد انفعالی برخوردار شوند، بلکه با بهکارگیری هنر و آیین ذرهبهذره، تاثیرگذاری بر محیط اطراف خود دارند. این تاثیرگذاری عمیقتر میشود و به گسترش میپیوندد تا جایی که حتی بر سختترین و مردانهترین ساختارهای جامعهشان نیز نفوذ میکند. برای من، تعریف عاملیت یک چنین چیزی است.

داوود: با قبول و پذیرش نقش هنرمند، آیا فکر میکنید که درگیر یک شرایط و سیستم خاصی شدهایم که ما را مجبور به ارتباط با آن و در نتیجه، به پرسش کشیدن و مورد خطاب قرار دادنش میکند؟ آیا فکر میکنید که هنرمند اکنون خارج از نقش “سنتی” هنرمند بودن، نقشهای دیگری را نیز بر عهده دارد؟

میترا: خود این سوال به نظرم ایجاد چالش میکند. من مفهوم نقش “سنتی” هنرمند بودن را بهطور کامل درک نمیکنم. شاید منظور این باشد که نقش هنر به شکل سنتیاش تنها کارکرد استاتیکی داشته باشد و در طول زمان این کارکرد تغییر کرده باشد. اما من با این ایده موافق نیستم. هر مثالی که به ذهنم میآید، هرچند ممکن است تاریخی یا حتی سنتی باشد، هنرمند را همواره در حال طرح پرسش، به چالش کشیدن فرضیات و تغییر و تحول میبینم. بنابراین، فکر نمیکنم که هنرمند اکنون نقش جدیدی پذیرفته باشد؛ آنچه تغییر کرده، شیوه فکر کردن و بیان است که به اقتضای زمان تغییر کرده است.

درباره بخش اول سوال، از آنجاییکه مهمترین ویژگی هنر را آزادی میدانم، فکر نمیکنم که هنرمند در هیچ زمینهای “مجبور” باشد. اما به شخصه، احساس میکنم در یک سیستم گیر افتادهام و در حال تلاش برای یافتن راهی به بیرون هستم.

پریا فردوس: با توجه به اینکه از سیستمی نام بردی که در آن گیر افتادی سوال اول داوود را طور دیگری مطرح می کنم؛ آیا این تعلق بافتاری یک امر الزامی است؟ و اگر تعلق به این بافتار، جامعهی مخاطب را محدود کند آیا برای هنرمند راهی وجود دارد که این محدودیت را در ارایه ی آثار خود کنار بزند؟ (چه در ارایه و چه در جامعهی مخاطبان)

میترا: دست کم برای من و در شرایطی که اثر مورد بحث ساخته شده، بله من ناچار بودم و امکان اینکه منفک از بستر زیستم فکر یا خلق کنم را نداشتم . اساسا همین ناچاری و یا احساسی از درماندگی ایدهی اثر را شکل داد. در مورد محدودیت مخاطب به نظر من طبیعی است که هر اثر محدودهی مخاطب خود را داشته باشد. من پروژه های زیادی را در طبیعت، محیط های بومی و فضا های عمومی و شهری ساختهام که طیف گستردهای از مخاطب را در بر داشته است و آثاری شبیه این پروژه، که احتمالا مخاطب محدودتری دارد. به عبارت دیگر چندان اصراری ندارم همهی آثارم مخاطب یکسان یا گستردهای داشته باشند.

پریا: در این راستا خود ذاتی هنرمند به عنوان یک انسان و حیات زیستهاش (در قالب یک ژست -روان و تن-) چه تاثیری بر تولید اثر دارد با توجه به اینکه برخی از کارهای برای من یادآور هانا ویکله و به خصوص آنا مندیتا است؟ (این سوال را در راستای صحبت خودت در مورد شیوهی زیست زنان عشایر مطرح میکنم و اینکه چهطور جنسیت و بدنمندی در روشمندی و شیوهی کاری تو ورود کرده است)

میترا: تصورش برای من سخت است که هنرمندی بتواند فارغ از تجربهی زیستهاش به هنر فکر کند یا چیزی خلق کند. شاید تنها این مساله باشد که تا چه میزان این تاثیر ملموس است یا نه. اساسا ایده ی این اثر و بیشتر پروژه های من کاملا بر اساس تجربهی زیستهام در یک فرهنگ بومی و آیینی پدید آمده است، چه از نظر موضوع و چه از لحاظ شیوهی کار. من به نوعی از هنر مفهوم گرا که در ارتباط با کنش های آیینی است گرایش دارم و ادبیات و طبیعت دیگر مولفه های مهم در تمرین هنری من هستند. همه این موارد مستقیما از حیات ذهن و جسم من در چنین موقعیتی ناشی میشود. مثال مشخص آن آثاری است که کاملا بر اساس رفتار آیینی شکل میگیرد و آیین مساله ای نیست که بتوان بیرون آن ایستاد و درکش کرد. همین موضوع به اهمیت مسئله تن و جنسیت درآثار من اهمیت میدهد چرا که نسبت میان تن و جنسیت و همچنین نوع گفتگوی این دو با طبیعت است که آیینها را پدید میآورد.

داوود: از منظر شما چه عامل یا عواملی باعث تفاوت بین یک هنرمندی که احساس مسئولیت در قبال جامعه میکند با گروهی مانند سیاستمداران یا دانشمندان علوم اجتماعی که در پی تصور کردن و ساختن آیندهای جدید هستند، وجود دارد؟

میترا: به نظرم حتی منطقیتر است که به شباهتها فکر کنیم تا تفاوتها، به این دلیل که این تفاوت بسیار اساسی است. هنرمند آزادی، حساسیت و خلاقیتش را به کار میگیرد. او میتواند مسائل را درونی کند و جوانب غیر قابل لمس را به نمایش بگذارد. او مستقل از حدود و مرزهای هر دیسیپلینی حرکت میکند و از این رو نه به تشریح مسائل بلکه به ادراک فاجعه یا موقعیت ایدهآل میپردازد. برای مثال، تجربهی خودم از بعضی آثار هنری با دغدغهی سیاسی-اجتماعی (در حرکت مدام میان اخبار و اطلاعات جهان امروز؛ موقعیتی که هر مهمی را به سرعت به امری پیشپا افتاده فرو میکاهد.) شبیه به یک وقفه یا مکث بوده است؛ وقفهای که شیوههای دیگر دیدن و اندیشیدن را پیشنهاد میدهد و با کمک به خلاقیت، امید به تغییر را زنده نگه میدارد.

پریا: با پذیرش اینکه از نظر تو هنرمند بایستی سمت مردم بایستد تا چقدر این امر شدنیست و در صورت تحقق چقدر تاثیر گذار، الهامبخش و کارکردی است؟ و آیا هنرمند بایستی خود را موظف به تاثیرگذار بودن بداند؟

میترا: نظر من الزاما این نیست که هنرمند باید سمت مردم بایستد و اساسا نمی توانم بایدی برای هنرمند تعریف کنم. من تنها میدانم که هنر بیش از هر چیز به آزادی نزدیک است یا بهتر است باشد. بنابراین در جامعهای دیکتاتوری احتمالا در بیشتر موارد سمت آزادی سمت مخالف قدرت است.

در مورد موظف بودن هم چنان که گفتم نمیتوانم وظیفه ای برای هنرمند قائل باشم، در مورد خودم میتوانم بگویم بیشتر به تعهد نسبت به خود هنر میاندیشم. در بارهی کارکردی بودن آن مطمئن نیستم و خیلی بستگی به شرایط اجتماعی که در آن فعال هستیم دارد اما دربارهی الهام بخش بودن، موافقم که تلاش هنری اساسا الهامبخش است و میتوان دربارهی کمیت و کیفیت آن فکر کرد.

پریا: و در ادامه آیا تنها هنرمند هست که در این جغرافیا باید بیانگر باشد یا باقی سمتهای هنری مانند گالریدار، کیوریتور، دیلر و … هم تاثیرگذاری مستقیم و به شکل یک گروه و یا پازل را دارند؟ یا با تعبیری این کنارهمقرارگیری (juxtaposition) به نظرت چگونه باید باشد؟

میترا: فکر میکنم به هر شکلی از بیانگری یا تاثیرگذاری در هنر فکر کنیم حاصل مجموعهای از انتخابهاست. در این انتخابها طبیعتا بازیگران دیگر عرصه هنر همچون گالریدار، کیوریتور، دیلر، منتقد و.. نقش مهمی دارند. چنانکه بارها دیدهایم هنرمندانی با گفتمان برجسته به حاشیه رفته و تولیداتی نه چندان مهم در معرض توجه قرار گرفتهاند. در مورد پروژههای من معمولا این کنار هم قرارگیری چندان موفق نبوده است، زیرا در چنین پروژههایی هم نقشهای دیگر از جمله گالریدار، کیوریتور و.. اهمیت بیشتر در ارائه اثر دارند و هم چالشهای بسیاری وجود دارد که آنان را کمتر به چنین پروژههایی متمایل میکند.

پریا: در این روند و تعامل هنر محلی و جهانی، هنر مدرن (امروز) ایران را کجای مختصات تصویر بزرگ هنر جهانی (big picture) میبینی؟

میترا: در مورد آثاری که به زمینههای بومی تعلق بیشتری دارند، من خیلی خوشبین نیستم. یعنی چندان نمونههای موفقی از نوع هنر را نمیشناسم. موفقیت منظور به رسمیت شناخته شدن به قول شما در مختصات تصویر جهانی. چرا که به نظرم نگاه جهانی/غربی به جوامع دیگر سهلانگارانه و همچنان استعماری است. به این معنا که همواره به تصاویر و ایدههایی سهلالوصول و اگزوتیک توجه نشان میدهند نه ایدههایی که به شناخت عمیقتر وابسته است.