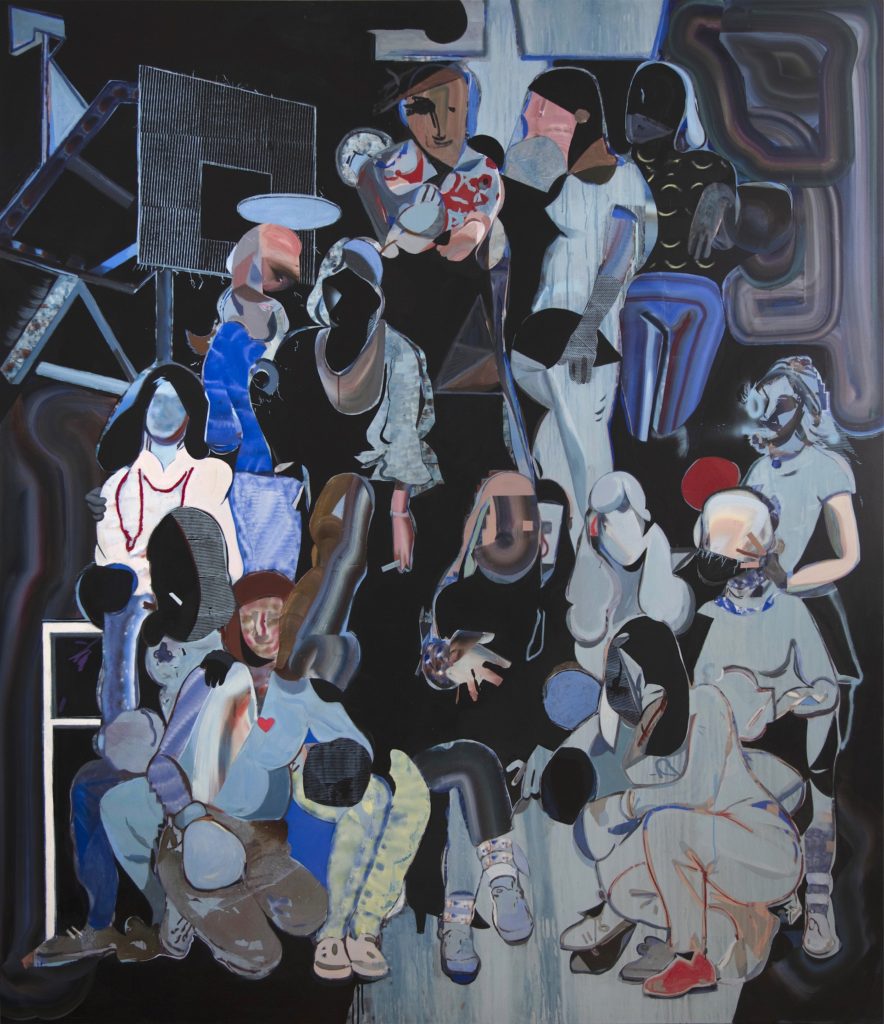

I am interested in painting as a possibility of encountering and investigating what images do in relation to what they are made of and how they appear to us. Pixelated broken TV images caused by Iranian government satellite jamming triggered my fascination with the moment of the glitch as a visible instance of the separation between the technology of fabricating and presenting images and what the images do and show. I use acrylic and various palette knives, rollers, and airbrushes to create complex and highly detailed surfaces where I can accentuate the significance of tools, material, and technology in the act of representation.

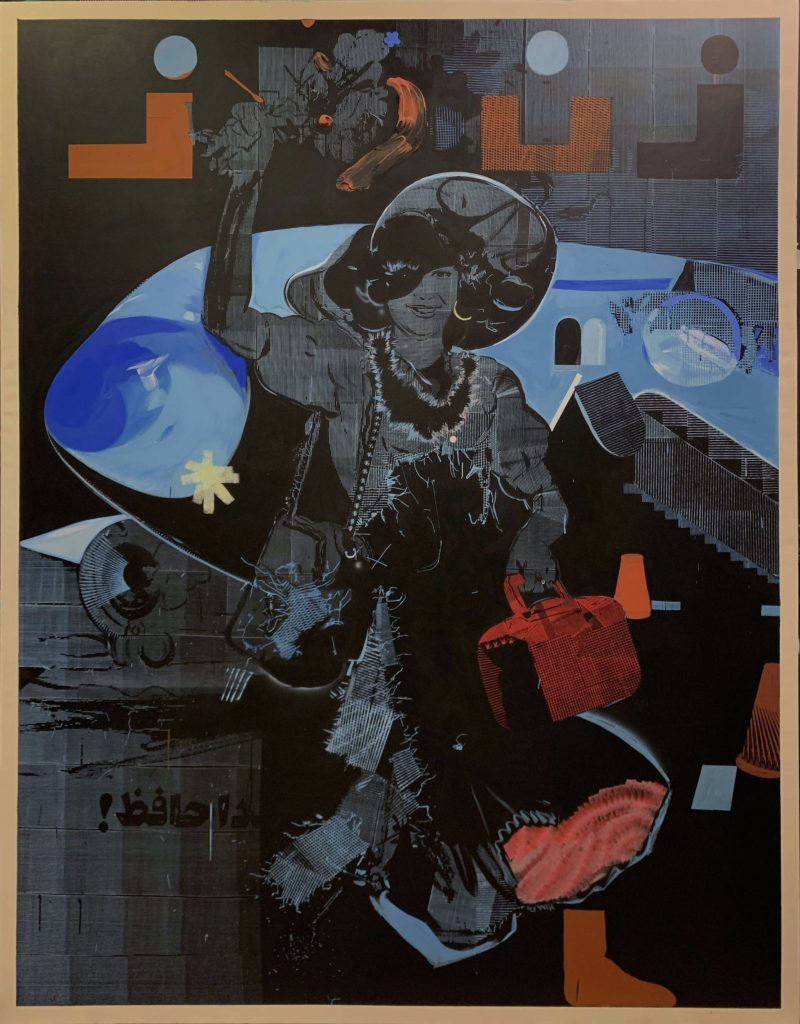

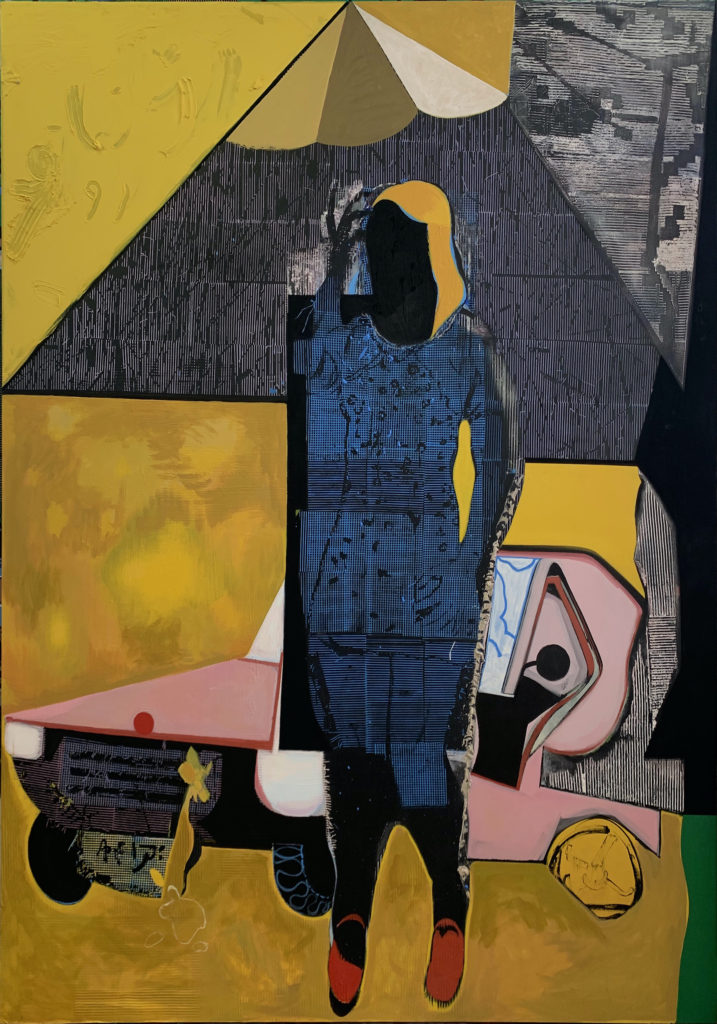

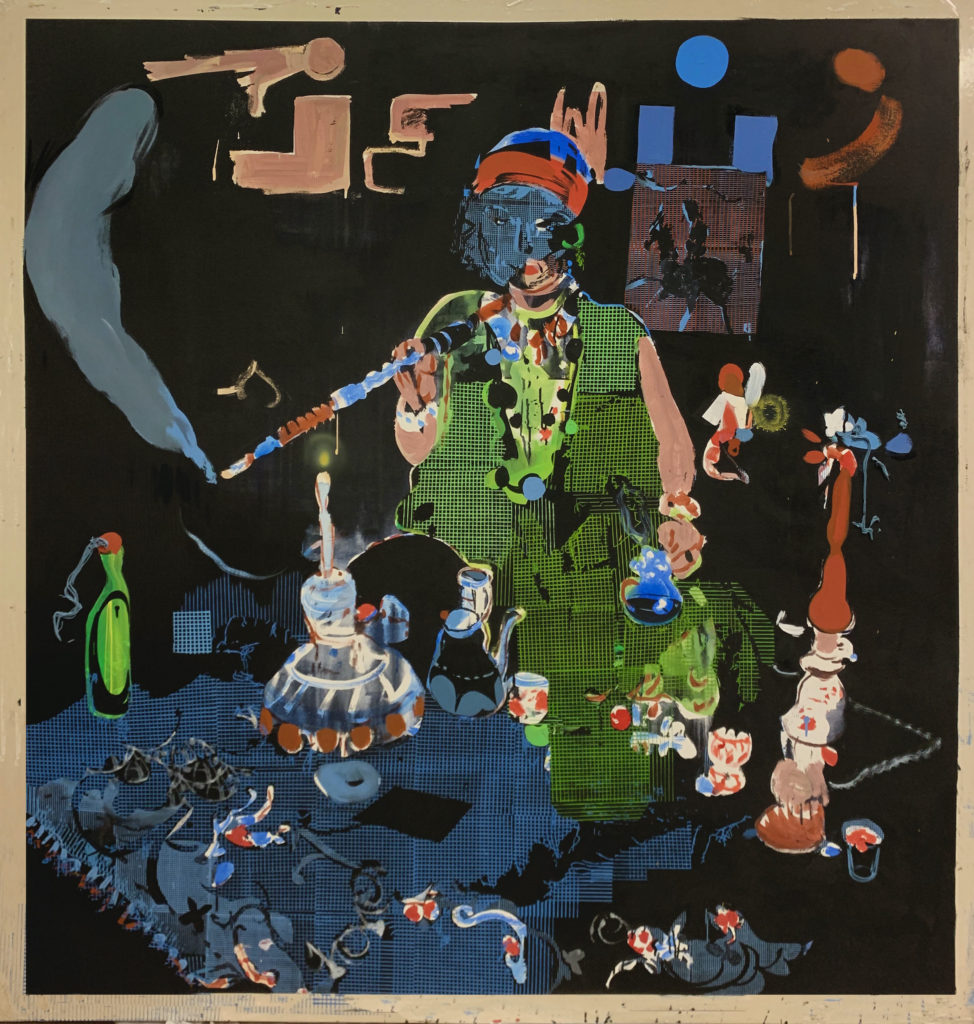

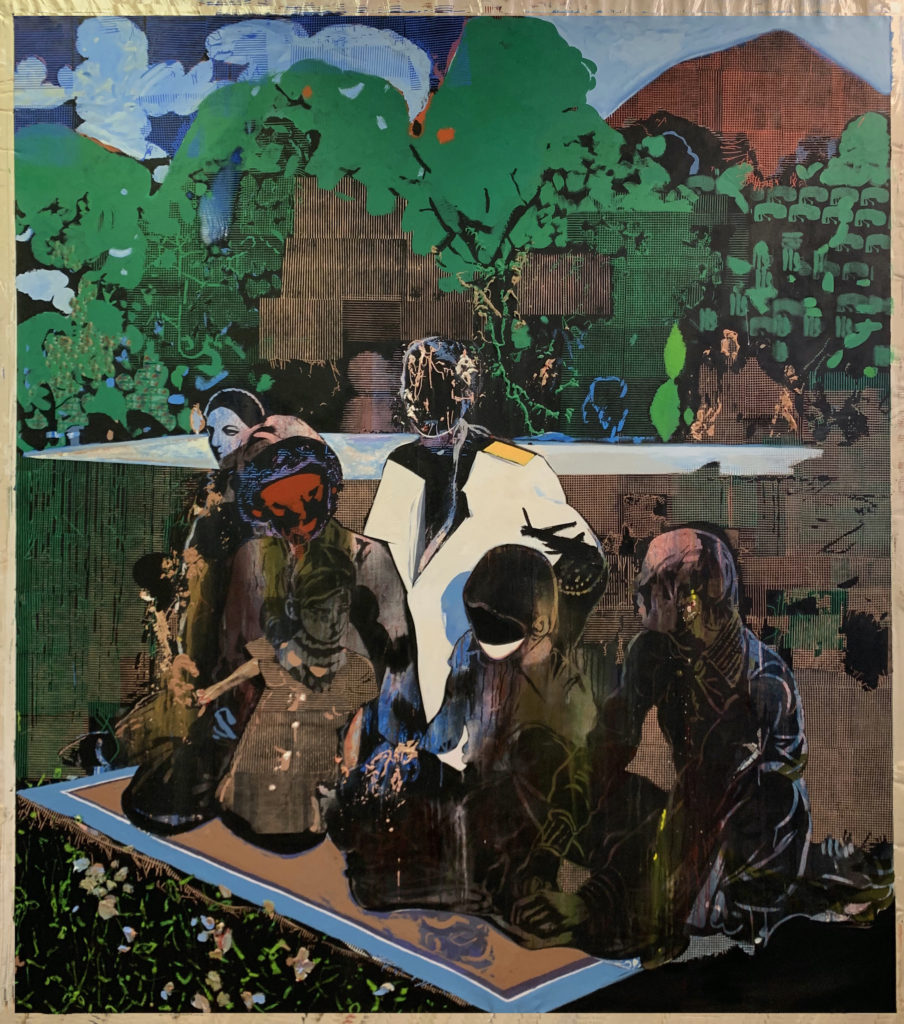

For my current series, I have been collecting and painting the covers of Zan-e Rooz (translated as “Woman of Today”), a weekly magazine founded in Iran in 1965. The focus of the magazine was originally Western fashion and style, love stories, gossip columns, and advertisements for American and European cosmetic products. Its pages often sported photos of models, including the celebrated Miss Iran, but after the 1979 Islamic Revolution, the magazine ignited aspirations to define the role of women in an Islamic society. Despite many rough patches and dramatic alterations to its content, Zan-e Rooz continued publishing. The photos changed and the magazine began to feature stories of revolutionary and religious figures with pictures of flowers or shrines, all united under a theme of anti-imperialism. I have chosen this particular magazine because it is mainly about and directed toward women, which brings a more visible and complex power structure into view while questioning the idea of aesthetics in the patriarchal society of Iran both before and after the revolution.

The covers of Zan-e Rooz magazine were often portraits of Miss Iran and candidates for Miss Teen Iran. Once, they were ever-changing physical beings living in Iran, selected and captured by analogue cameras on sensitive photographic paper whose image became visible through a series of chemical reactions. Photographs were captioned, laid out, and mass produced by a printing press. Years later after the revolution, the images were archived, digitally photographed, or scanned and turned into algorithms, now visible through pixels on the screen of my phone, sorted into folders on my computer, and accessible on the internet. Perhaps they are stored at megastructure data centers like SUPERNAP in Las Vegas or Inner Mongolia in China. All of this is happening as the particles of those living beings and those paper magazines are changing and decaying. I am interested in how the material of the painting and the act of painting itself reveals or represents this trajectory. The simultaneity of multiple material applications to create the painting reflects the various modes of image reproduction and dissemination that occur at any given moment in the history of an image. This process brings me to the question: What am I actually painting?