Sara Sallam, b. 1991, Giza Egypt.

Lives and works in Delft, Netherlands.

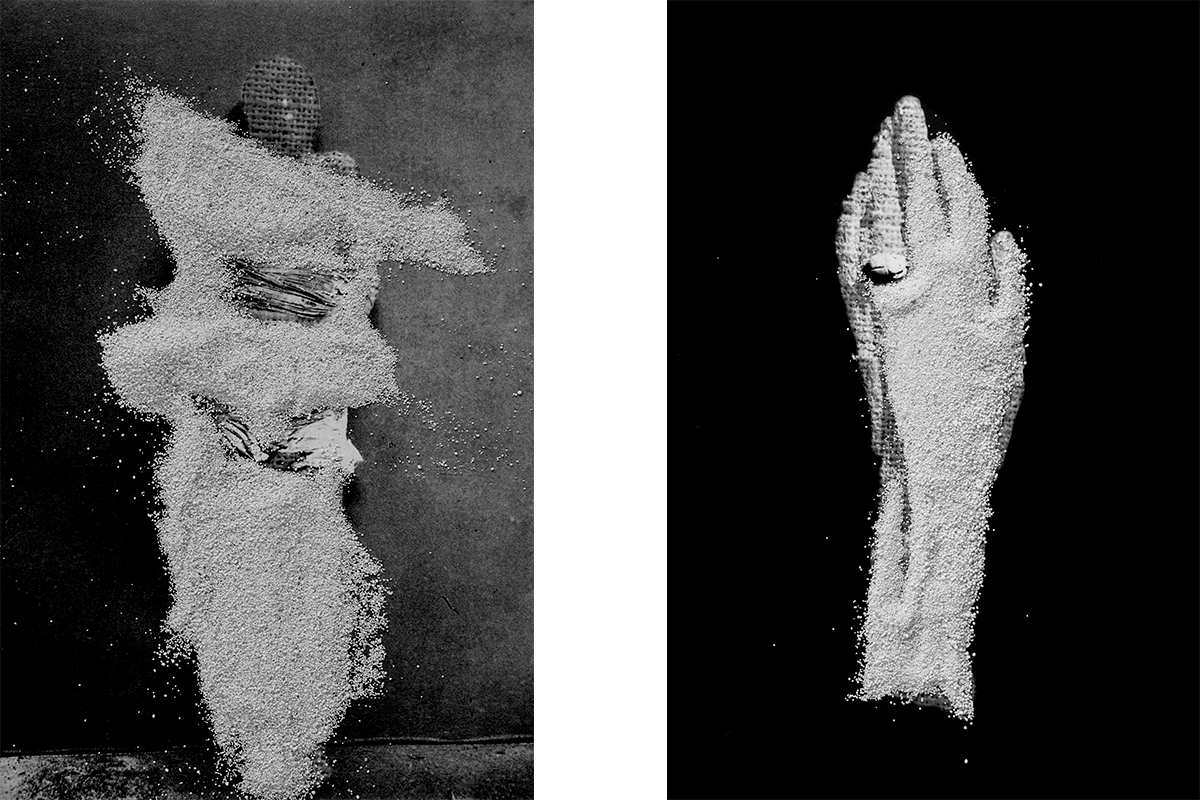

Sallam is a multidisciplinary artist, designer, visual researcher, and bookmaker. She works with photography, video, and writing, often re-appropriating and manipulating archival material to invite hidden meanings to emerge. Themes of absence, loss, and longing run throughout her work in which she explores ways of portraying things we cannot see and people we can no longer meet. Against this backdrop, she reflects on growing up in Egypt, criticising the colonial heritage manifested in tourism, archaeology, and museum practices preventing Egyptians from relating to their past and ancestors.

Sallam holds a BA in Media Design from the German University in Cairo, an MA in Photojournalism and Documentary Photography from the London College of Communication, and an MA in Film and Photographic Studies from Leiden University. Her work was exhibited internationally and was awarded grants from Magnum Foundation, Prince Claus Fund, the Arab Fund for Arts and Culture, and Mophradat. She is represented by Tintera Gallery.

The first ancient Egyptian mummy to travel to the Netherlands arrived in the early seventeen hundreds. Some 300 years later, I arrived there. Not long after, I found myself searching for home outside of home. Strangely, I needed not to look for long.

I found familiar bits and pieces of home scattered around. The obelisks of my ancestors accentuated public squares. Their statues decorated building facades. Their belongings filled shelves and cabinets. I even met them in their newly furnished homes with glass vitrines, marble floors, and pale coloured walls.

I heard whispers, echoing from the past, of men who were obsessed with anything my ancestors touched. They narrated their adventurous tales in exotic, desert wastelands. They spoke of their victorious conquests and scientific discoveries. They showed me the diaries they wrote there and the souvenirs they brought back.

I saw how my history became a fictional story shaped by imaginative minds. I watched it unfold in front of curious spectators. They gasped as one of my ancestors came back to life. They jumped up when he performed magical spells bringing chaos into their world. And they were relieved when men like them established control by killing him once again.

In my new home, my longing for familiar faces pulls me closer to the company of my immigrated ancestors. They are kindred spirits, resonating with me across time. Seeing their humanity forgotten is painful and makes me wonder, when do we stop mourning the ones we love?